Woden” Head Sceat c. 710-760.£1,000-2,000

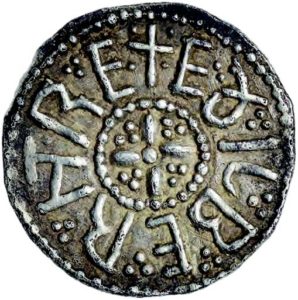

Offa (757-796) Penny, Canterbury, Eoba. £10,000-15,000

As the year has panned out, one could be easily forgiven for wanting to look forward rather than back. With 2021 heralding the 1,150th Anniversary of the coronation of King Alfred of Wessex, it gives Spink great pleasure to do both by presenting one of the larger offerings of his coinage to appear in recent years, alongside a succession of truly rare and iconic numismatic treasures from the most formative years in the history of the British isles. Migrant influxes, economic turmoil and political fragmentation – this may sound like our own times – but the same is true in AD 871, and just over the horizon? The Vikings are coming…literally.

But where did it all begin? What are the ‘Dark Ages’? Why was Alfred’s achievement sufficient to earn him the nickname ‘The Great’? And what is scarier than a Viking? Whilst a number of these questions continue to puzzle numismatists and historians, the melting pot of cultural and social practices within this island in the two centuries following the collapse of Roman Britain left her inhabitants very much at the forefront of a spiritual battle for its very soul. The power vacuum caused by the withdrawal of the Roman Army in AD 410, presented a rich breeding ground in which prexisting civic and regional leaders could be-gin to carve out their own territorial control. Dynasties sprang up across the land, from the Wuffingas (‘Wolflings’) of East Anglia to the Iclingas (‘Descendants of Icel’) of Mercia. The arrival of Christian missionaries from Rome in the last decade of the 6th Century began a pattern of conversion firstly in Kent, then East Anglia, and eventually Northumbria that saw traditional values of Pagan multi-deity worship supplanted by Christian teaching underpinned by baptism of the Royal courts in these fledgling kingdoms. Most converted, Mercia resisted, pro-voking fierce conflict that plagued the middle of the 7th Century, and loaning to history famous warmongers like King Penda, and to archaeology the earthly deposition of the Staffordshire Hoard and the wondrous Sutton Hoo ship burial.

For numismatists it is not until the last decades of that Century that coinage reappears, mainly through continental importation which in turn became permissible specie at a time of prolonged accord between the warring factions. As much as AD 650 records great unrest across the island, AD 680 testifies peace through which fledgling economies could develop and ultimately sow the seeds of Alfred’s future prosperity. An example of a coin of this period begins the Ennismore sale. Termed a ‘Sceat’ or ‘Proto-Penny’ its design is stark, and a true testament to the age in which it was struck. On the one side, the image of Woden (Odin), Norse god of War, and on the other a Christian ‘cross pommée’ – together, as if in perfect harmony. The message behind the blending of these two conflicting religious ideas is not exactly clear. The imagery could reflect a deep-seated concern for the afterlife; to spiritually ‘hedge one’s bets’. However if there is any significance in the unprecedentedly lengthy reigns of Ealdwulf (663-713) and AElfwald (713-749) in East Anglia, and Ethelbald (716-757) in Mercia, the symbiosis of the Pagan and the Christian could have been a regally-sanctioned promotion of unity regardless of individual persuasions. However, as has been witnessed throughout history, from Rome to Iron Age Britain, it is not long after the advent of coinage, that its role as currency becomes superseded by its ability to transmit messages at the designer’s behest. Soon develops an acute self-awareness of the role of the individual, with designs swiftly evolving to accommodate this.

One can find no greater example of this emerging numismatic trend for ‘Majestic self-importance’ than in the coinage of King Offa, a ruling hegemon with influence over East Anglia and Kent, as well as his own burgeoning territory of Mercia by the late 8th Century. The Ennismore coin shows a supreme artistic skill wholly incongruous with our general perception of ‘Dark Age Britain’ with its wonderfully classical-stylised rendering of the ‘King’ evidently loaned from a Roman Imperial prototype.

Furthermore, it testifies the growing role of those around him, for whom the production of the Royal coinage became a route for their own self-promotion. Even within a numismatic record as rich as King Offa’s, the Ennismore coin is particularly remarkable with its sheer competency and spectacular artistic flair oozing with the power and control centred at the heart of the Mercian kingdom. In a delightful state of preservation, this striking coin has a pedigree to match – traced back to the ‘Rome Hoard’ (c. 1830). Evidently this coinage was not just to be flaunted in the Britain, but very much in front of the God’s anointed too.

With self-promotion however comes risk, especially if your own power has been guaranteed by the Overlord Offa. Æthelberht II of East Anglia appears to have crossed this line, perhaps in the simple act of recording his Kingly title ‘REX’ in association with his own name. This unique coin now part of the Ennismore collection, was recovered by a metal detectorist rather prophetically during a hailstorm in East Pevensey in March 2014, and presently holds the record as the most expensive Anglo-Saxon silver coin ever sold. As is known from the Christian tradition, the hapless King Æthelberht had been due to marry Offa’s daughter Ælfthryth. As he embarked upon his journey to Mercia, a great many omens foretold of the impending disaster, whether they be earth tremors or rapidly forming mists that impeded the young King. Nevertheless he would carry out his fateful journey, only to be beheaded soon after arriving at Offa’s court at Sutton Walls. The true motive behind this shocking murder is unclear, it was later suggested that Queen Cynethryth had schemed Æthelberht’s demise with one chronicler lamenting: ‘so ended the life of Æthelberht, like St. John the Baptist, entangled in a woman’s snares’, but in truth the event is still shrouded in mystery.

In retrospect, Offa may simply have intended to remove a troublesome client King who threatened to re-establish an independent East Anglia, expecting the death to simply be forgotten. However, the chance discovery of the East Anglian king’s body in the River Lugg, and a subsequent encounter with a blind beggar (later cured) on its route to burial ensured the King became revered as a local Saint, a patron of Hereford Cathedral, and a source of cult worship across East Anglia. Evidently tormented by his actions, Offa sought to atone for the sin of having killed a martyr. In a shrewd piece of political theatre no doubt driven by his own premonitions of mortality, he sought out the story of Britain’s earliest Christian idol. He found St. Alban, a convert executed by the Romans in the late 3rd Century near the town of Verulamium. There he chose to found a new monastery, latterly the Abbey of St Alban’s, alma mater of the only English Pope, Adrian IV, and the medieval historian Matthew Parys whose surviving annals ironically record Offa’s shame. After Offa’s death, the client kingdoms of East Anglia and Kent would rise up again and assert their independence. Both were suppressed by Offa’s successor Coenwulf, but the period of expansion had come to an end; within thirty years Wessex would emerge as the significant presence south of the River Thames.

With Lindisfarne seared in memory, the threat of Viking raids became very real. Alfred however, as the youngest of five Royal brothers in the house of Wessex was probably little troubled, safe in the knowledge he would never be King. At just six years of age, Alfred began to be disabused of this notion, hearing of his father Aethelwulf and elder brother Æthelbald’s victory over a heathen army at the Battle of Aclea. A decade later, the third brother Æthelberht would die as the Great Heathen Army wintered at Thetford. With the accession of Æthelred I, the North of England fell to the Vikings. York, November 866; Nottingham, 867; East Anglia, 869. In 868, Alfred fought alongside his brother against a raid by Ivar ‘the Boneless’ into neighbouring Mercia. Angered by the affront, the Vikings launched a full-scale assault on Wessex. In January 871, the Vikings defeated Æthelred at the Battle of Reading, however the result was partially reversed at Ashdown, largely due to the personal exploits of Alfred. Two further defeats at Basing and Meretun left Wessex resorting to peace negotiations, and worse still Æthelred was now sick. Shortly after Easter, he died. Alfred, the unlikeliest of Kings in 849, was now just that at the age of just 22, and he faced seemingly insurmountable odds.

Following the Saxon defeat at Wilton in May 871, a financial settlement ensured the Vikings vacated Wessex for London. The Croydon find (1862) provides a snapshot of the ‘Danegeld’ payments made following such a treaty, as well as the widescale disruption Viking incursions had in this period. Ennismore incorporates an Alfredian issue much in the style of that coinage, and evidently struck at his lowest ebb. In 876, the Vikings returned at Wareham with various pitched battles being partially repelled by Alfred before he is forced into retreat to Æthelney. In May 878, Alfred summoned a meeting at Egbert’s stone – this would be the start of the fightback. Days later Alfred would meet Guthrum at Ethandun [Edington, Wilts] and the fate of England for generations would be settled. A decisive west-Saxon victory crushed Viking aspiration, forced Guthrum to convert to Christianity and adopt the name Aethelstan, and England to be demarcated into Wessex (incorporating Mercia and Kent) and ‘the Danelaw’.

By 880, London existed as a border town within the Mercian zone under the overlordship of Alfred. This settlement was marked by a new coinage; now the most iconic of Alfredian types: the ‘London Monogram’. A fine series of this coinage is represented in the Ennismore cabinet, from one of the earliest variants recovered from the mysterious Bucklersbury Find (1872), to the more the stylised portrait types that reflect regional legend spellings of his name. Less well known, however is the inspiration this prolific coinage had in the Danelaw, with remarkable imitations providing the first specie there. It is often said that coinage can be used as a window on the past. No greater lens can be provided than a contemporary imitation, for it provides the numismatist with not only an object, but equally an eyewitness’s interpretation of it too.

Alfred died as ‘King of the Saxons’ in AD 899, by which time the tide had firmly turned in favour of the Wessex cause. His son and daughter, Eadweard the Elder and Æthelflaed would soon take up their father’s mantle. Following the Battle of Holme (AD 902), the challenge of Æthelwold, son of Alfred’s older brother Æthelred I ended, and the pathway clear for their reconquest of England over the next two decades. By AD 918, the sibling pair had reconquered East Anglia, and fortified most of Mercia and Southern England. With Æthelflaed’s influence in the north-west, it is assumed that she was responsible for the ‘exceptional types’ struck in this region in the name of her brother. One such example of this extremely rare coinage is Buga’s floral type of which only four examples are known, two of which are in institutional collections and the other unseen to commerce since 1977. The Ennismore collection features the only other known coin pedigreed back to the fabled Montagu cabinet, sold in 1895.

At the same time, the increasingly restricted territories of the Danelaw produce a fascinating series of coinage, likely inspired by the influx of Hiberno-Norse rulers from Dublin. The imposing designs of the Mjölnir [hammer] and the sword can be seen on the excessively rare issues of Sihtric Cáech from the ‘Five Boroughs of Danish Mercia’. What could possibly be more terrifying than a warrior Viking? Perhaps one with only ‘one-eye’ as his epithet would suggest. This 10th Century “Vik-lops” however has been recently romanticised by Bernard Cromwell as the wise and cunning son-in-law of the main protagonist Uhtred of Bebbanburg in his novels ‘The Saxon Stories’. More familiar issues from this period are the ‘Raven’ types of Ánláf Guthfrithsson struck at Jorvik, and like our first coin directly allude through their iconography to Odin. Our perception of simplistic warmongering Norsemen is noticeably enriched by the numismatic finery of these elaborate and intricate Viking designs. Shortly thereafter follow perhaps the ‘sleeping jewels’ of the Ennismore cabinet. A stunning series of Hiberno-Norse issues of Ánláf Sihtricsson and Ragnald Guthfrithsson, all excessively rare; all on offer amongst the finest of their respective types known. Rather aptly, as Offa, Cynethryth and Aethelberht II have been reunited in this collection, as to has Ragnald with Eadmund, who in his conquest of the North successfully drove the former out of York in AD 944. Far removed from any potential bias, the author entirely concurs with one contemporary epithet for King Eadmund – ‘the Magnificent’, which he hastens to add is also our assessment for this exciting evening auction.

The Ennismore Collection of Anglo-Saxon and Viking Coins will be offered for sale in our London Showroom on Tuesday 15th September 2020 at 6pm. For more information, contact [email protected] and [email protected].