By Harriet Hassard-Shirley

In 2019 I began a four-year degree in French and Philosophy, which involved a year abroad studying in France. The two were taught as separate studies, and so I was fortunate to enjoy a variety of subject areas, as well as the experience of learning in an entirely different education system. The French side of my degree involved more than solely studying the language, with modules in French history, art and literature taught with equal importance. The philosophy side consisted of historical based modules on the history of philosophy, whilst also delving into areas of ethics, morality and freedom, all of which greatly improved my skills in practical reasoning and judgment. It is this development of reason, argument and logic that I appreciate so much about philosophy and has been my motivation to continue to learn within this realm since my graduation. And so, with these thoughts in mind, on exposure to the undoubtedly magnificent artistry of French banknotes, naturally I found myself drawn to the banknotes featuring French philosophers or referencing la philosophie in general.

“Coupled with the spendings and expensive pastimes of the monarchs portrayed in the press, it is no wonder that this contributed to the discontent that began to grow rapidly in France during the late 1700’s”

Caricature Showing Marie Antoinette as a Dragon, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

It is often the case that the issuing authority showcases an image on a banknote which holds cultural significance and evokes thoughts of national identity and pride. In this case, the choice made by French issuing authorities to present les philosophes on French banknotes, was undeniably a significant decision made with purpose. Before looking at the remarkable notes in question, a discussion of where this appreciation for philosophy was founded, particularly looking at the historical context of pre-revolutionary France, is essential in order to understand their symbolic nature.

Following the end of the American Revolution in 1783, the need for change was echoed throughout France. Significant aid from the King of France, Louis XVI, to help bring the revolution to a halt created a tumultuous economy and left France on the brink of bankruptcy. In addition, prior to the American Revolution, the Seven Years’ War between 1756 and 1763 shook France’s economic stability. As a result of the instability and mass of debt, taxes were raised in an attempt to combat this. The First Estate (clergy) and Second Estate (nobles) in France were exempt from this taxation, leaving the burden with the Third Estate (common people). It became clear during this period, that the gap between the classes was continually expanding, creating political agitation and hostility by those weighed down with heavy tax, while the wealthy continued to live life in excess.

A notable figure during this period, whose life I have always been intrigued by and whom much of this anger was directed towards, was that of the Queen of France, Marie-Antoinette. During her reign, Marie-Antoinette ultimately became the symbol of royal expenditure and extravagance. Her lust for luxury, which involved elaborate partying at the Palace of Versailles, her expensive eye for couture and the controversy surrounding her love life, altogether contributed to the growing discontent that eventually led to the French Revolution in 1789. A major factor that played an enormous role in damaging the reputation of the Queen was the use of propaganda. With the mass production of caricatures and libelles (political pamphlets, plays or short stories), Marie Antoinette was accused of sexual debauchery, affairs, illegitimate children and political intrigue in favour of her Austrian heritage, to name a few. Despite the inconclusiveness of some of these accusations at the time, the slander spread about the Queen was often taken as truth and left people outraged by the state of the Ancien Régime.

This caricature of Marie-Antoinette is one example of propaganda spread amongst French people around the revolution. The depiction presents the Queen as a harpy, a half human half bird mythical creature, often used to refer to cruel women and associated with danger and greed. Here, Marie-Antoinette is dehumanized and presented as monstrous bird of prey, with the sharp double tail and wings appearing devil like and associating Marie-Antoinette with evil. This caricature was likely deployed as propaganda after the French Revolution, with the birdlike feet of the harpy standing on the Constitution of The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizens, established in 1789. This is a clear reference to the sentiments of Marie-Antoinettes disrespect for the rights of French citizens and lack of humanity that continued to circulate after the fall of the Ancien Régime (Colwill. E, 1989).

Louis XVI, while not targeted to the same extent, was also negatively depicted and targeted in libelles and caricature. His lack of control over the press, who had been depicting his wife in incredibly defamatory lights, added to the falling respect that the French people held for their King and Queen before the revolution. The libelles were predominantly read by the lower class who were facing extreme hardships concerning their standards of living. Coupled with the spendings and expensive pastimes of the monarchs portrayed in the press, it is no wonder that this contributed to the discontent that began to grow rapidly in France during the late 1700’s.

During this period before the French Revolution, another key component igniting the fire of the Revolution, was the Enlightenment. The Siècle des Lumières began in the 17th century, with philosophical and political discussions becoming more and more prevalent in society throughout the 18th century. Prominent ideas included thoughts of liberty of the people and equality amongst the classes. The Enlightenment favoured knowledge derived from rational and empirical thought, enforcing central doctrines of personal liberty and religious tolerance, as opposed to an absolutist monarchy and authority of the church on matters of the state. With literacy rates rising in Europe and popular books of the enlightenment thinkers increasing in circulation, France saw a considerable shift in society and public thought. Enlightenment philosophers from all across Europe began to share revolutionary ideas, aiming to abolish the power and control of the elites and give more authority to common people. On 22nd September 1792, the first French Republic was officially established in France. The motto Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité first appeared in France during the French Revolution, and remains the national motto today, standing as legacy to the Siècle des Lumières and a reminder of French values.

Today, the Baccalauréat still includes a compulsory philosophy component, which highlights the importance given to critical thinking and philosophical reasoning

After the French Revolution, philosophy became a well-respected and appreciated study. In 1808, Napoleon launched the Baccalauréat, including the subject in the first exam, and from this point on, philosophy became a mandatory subject in French secondary education in the late 19th century. Today, the Baccalauréat still includes a compulsory philosophy component, which highlights the importance given to critical thinking and philosophical reasoning. For the French people, this love of wisdom and the study of philosophy itself is a fundamental pillar of society, allowing freedom of thought and the ability to philosophize ideas independently, creating a society of informed and logic driven citizens voting in French elections. While I did not take the Bac myself, studying under the French education system in an environment where the subject is so appreciated was an incredibly rewarding experience. During my time in France, I took various philosophy modules, including Philosophy of Science where I delved the works of a renowned philosophes of the Enlightenment in France. One figure in particular, who also appears on a 100 Francs banknote, is that of Descartes.

René Descartes was a philosopher, scientist and mathematician, whose work remains widely celebrated today. Descartes emphasized the use of reason and scientific method in understanding and drawing information about the natural world. Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) is one of the most significant texts to date and is considered a foundational pillar of modern Western philosophical thought. On this 100 Francs note, Descartes appears to be holding a compass and pointing to a piece of paper, a reference to his longstanding contributions to science and mathematics (Pick 101, BNB 976).

Descartes on 100 Franc note ND (1944), (Pick 101, BNB 976).

On the obverse of this note in the distance, Clio, the Ancient Greek Muse of History, is visible holding a large book, with an hourglass present at the left. Looking at these images in conjunction with one and other, we can infer that the obverse of this note is making a reference to the significance of Descartes teachings, who is a valued figure in French history to be remembered in the past, present and future.

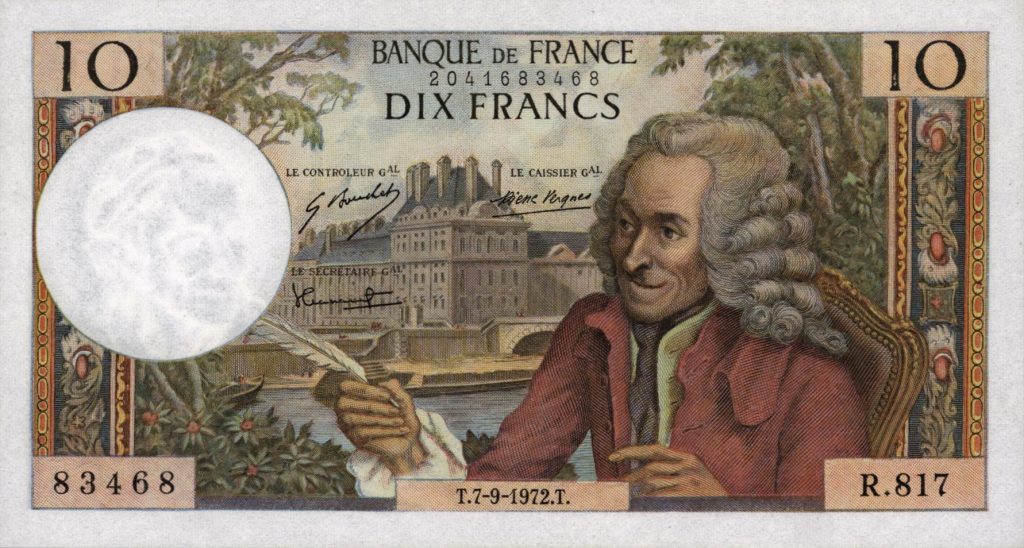

Various other references to philosophy and philosophers have appeared on French banknotes over the last century, continuing to highlight the significance of philosophical thought in France. Voltaire is featured on a French 10 Franc note from 1963-1973 (Pick 147, BNB 1005). Named François-Marie Arouet at birth, Voltaire advocated for the freedom of religion, of expression, equality and separation of church and state. Voltaire’s philosophical works were often written as short stories, with his most celebrated novella Candide (1959), a satirical philosophical tale following the adventures of a young man encountering misfortunes through his life. In 1764, Voltaire published the Dictionnaire Philosophique, a collection of alphabetically organised short essays and another prominent work of the Enlightenment era.

“For the French people, this love of wisdom and the study of philosophy itself is a fundamental pillar of society, allowing freedom of thought and the ability to philosophize ideas independently, creating a society of informed and logic driven citizens voting in French elections”

Voltaire on 10 Franc note ND (1963-73), (Pick 147, BNB 1005)

Charles Louis Secondat, Baron de la Brède et de Montesquieu, commonly known as Montesquieu, shared many of the same ideas as Voltaire and is also featured on the French Franc (Pick 155, BNB 1012). He was a political philosopher during the enlightenment, who is best known for his theory of the separation of powers, believing the government should be responsible for maintaining law and order, with the needs of all citizens in mind. Montesquieu is depicted at the forefront of a 200 Franc banknote, with an allegorical woman holding a sceptre to the left of the obverse. Next to her appears a set of scales and a sword at the centre reading l’Esprit des lois. The presence of these images is a reference to Montesquieu’s political work, with l’Esprit des lois (The Spirit of Laws), a hugely influential political text of the enlightenment era written in 1748. The appearance of the sword and the scales is a known symbol of justice, highlighting the objective of the influential works written by Baron de Montesquieu.

“Philosophy teaches us fundamental and invaluable skills in reasoning, argument and logic, that can be applied in countless areas of life.”

Montesquieu on 200 Franc note ND (1981-94), (Pick 155, BNB 1012).

Philosophy appearing on banknotes is not only presented through les philosophes alone, but also through philosophical symbolism. This symbolism is perfectly illustrated by a 500 Franc note, of which I was unable to uncover an image for but can be found in the Banknote Book (circa. 1931, see BNB 962). The obverse of this note presents two seated figurative women. On the left, one of the women symbolises science, holding a microscope with a chemistry beaker below, whilst on the right, the other women symbolise philosophy, holding a notebook and an olive branch with a globe and a stack of books at her feet. At the centre of the reverse of this note, an allegorical woman holds a torch in her left hand and an olive branch in her right hand. This woman is likely the embodiment of liberty. Finally, on the bottom corners of the reverse, an allegorical man appears to represent work on the left, whilst the right side presents a woman with her children, embodying family and fertility. This banknote is a clear depiction of the values that France wishes to represent, with the inclusion of philosophy amongst other central values highlighting the respect given to this study in particular.

Overall, les philosophes and philosophy in general are significant in France and to the foundations of the French Republic. The French nation, since the revolution and the works of Enlightenment philosophers have maintained this study, to motivate citizens to become informed voters and to encourage people to think as individuals, for the greater good of the collective nation. I myself, having studied philosophy for 6 years, with the experience of studying at a French university, truly understand the importance of critical thinking and reasoning. Philosophy teaches us fundamental and invaluable skills in reasoning, argument and logic, that can be applied in countless areas of life.

References:

Colwill, E. (1989). Just Another Citoyenne? Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790–1793 ‘WOMEN…THIS REVOLUTION MUST CHANGE YOUR MANNER OF THINKING, MAKE YOU SEE EVERYTHING DIFFERENTLY’.

By Harriet Hassard-Shirley