By Mark Jones

“Wyon’s life-changing break, came when his uncle Thomas, who had returned to London, asked him to come and stay”

Ceres, 1813. Society of Arts prize medal for agriculture

It might seem strange to claim that William Wyon was and is Britain’s most truly popular artist. After all he is hardly a household name today. Yet it is probably true that his work has been seen by more people than that of any other British artist in history. A brilliant modeller in low relief, whose talent for flattering portraits won him the favour of George IV, William IV and most important Queen Victoria, his coins circulated in Britain, and around the world, and were seen and used by hundreds of millions of people. Outdoing even the coins, Wyon’s portrait of Victoria which appeared on her stamps, from 1840 until the end of her reign, was printed in many billions, becoming familiar to much of the world population.

The Wyons, like so many British artists, were immigrants. They came to Britain from Germany, following the new Hanoverian dynasty, and established themselves as silver chasers in London in the mid-18th century, before moving, later in the eighteenth century, to Birmingham as ‘modellers, die sinkers and art metal workers’. In 1809 William, born in Birmingham in 1795, left school aged fourteen and was apprenticed to his father, who had engraved many of the dies for token coins, struck in Birmingham to mitigate the shortage of small change and meet the desires of collectors. Wyon’s life-changing break, came when his uncle Thomas, who had returned to London, asked him to come and stay. Aged only 16 Wyon had an ‘antique figure of Antinous’, engraved in steel, accepted by the Royal Academy for its summer exhibition in 1812 and went on, in 1813, to win a gold medal from the Society of Arts for a head of Ceres. Victorious in a competition for the post of Second Engraver, on a salary of £200 a year, he moved into the recently completed Royal Mint at Tower Hill in 1816 and embarked on the career that was to make him famous.

The Mint, with its new coin presses powered by Boulton and Watt’s coal-fired steam engines, was enormously busy striking a new coinage. It turned out 44 million coins in 1816 and 50 million in 1817. The immense workload was split between William Wyon, who was responsible for engraving the reverse dies and for the inscriptions, and his cousin Thomas, the Chief Engraver, who engraved the obverse portraits of George III after a cameo portrait by Benedetto Pistrucci. When Thomas became ill William took on much of his work and so naturally hoped that, when Thomas succumbed to pollution1 at the Mint in 1817, he would succeed him. But it was Pistrucci, not Wyon who was chosen to carry out the functions of the Chief Engraver. Wyon was bitterly disappointed and, following Thomas Simon’s example, made two ‘petition crowns’, demonstrating, he hoped, that native talent had been unfairly overlooked.

Left: Lewis Pingo after John Flaxman, Society of Arts Prize Medal, British Museum. Right: William Wyon’s new design for the medal, 1820. British Museum

William Wyon ‘Let not the deep swallow me up’. 1824. British Museum

The reverse of the crown shown here was based on a drawing by Henry Howard RA, but Wyon, who was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in that same year, was becoming increasingly confident of his own abilities as a designer. He turned a request from the Society of Arts, that he make a new copy of their Minerva die, designed by the great sculptor John Flaxman, into an opportunity to come up with an original design of his own, for which the Society awarded him its large gold medal.

As Wyon’s reputation grew, his income from private commissions increased, enabling him and Catherine Keele to marry in 1821. Better still George IV so disliked Pistrucci’s portrait of him for the first coinage of his reign that he looked instead to the sculptor Francis Chantrey and to William Wyon for a more sympathetic second coinage. This was reckoned, by contemporaries to show George ‘too young and handsome’, an early example of Wyon’s talent for making even the least promising subject attractive, while retaining a plausible likeness. Wyon’s success with this coinage was eventually recognised by his appointment as Chief Engraver in 1828, with the salaries of the Chief and Second engravers split equally between him and Pistrucci, leaving them both rather embittered on £350 a year rather than the full salary of £500.

Wyon engraved new coin dies for British possessions elsewhere, including the Ionian Islands and the Madras Presidency in India, and for other countries, including Mexico and later Portugal. Prestigious organisations like the Royal Academy and the Royal Society turned to Wyon for new versions of their medals, and new societies, like the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck [later the RNLI] gave him opportunities for creative invention. For the lifesaving medal he came up with a scene of intense and concentrated drama, representing himself as the rescuer snatching the drowning man from certain death.

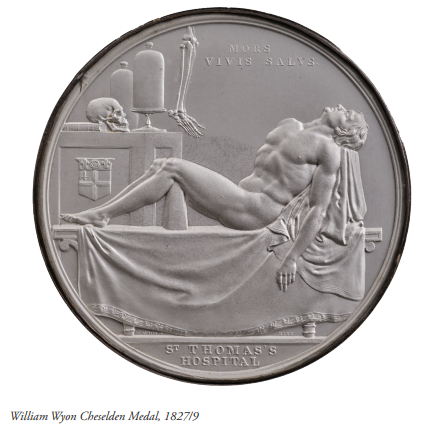

Reward and prize medals, which were becoming ever more popular with the earnestly improving institutions of early 19th century Britain, became a staple and profitable source of income for Wyon and his young family. The Cheselden Medal, a prize medal for anatomy at St Thomas’s Hospital, London, with its beautiful, if slightly macabre, composition centred on a finely muscled corpse, compositionally balanced by a hanging skeleton and a skull, did much to confirm his reputation as a modeller and engraver of exceptional talent, reaffirmed by recognition from the leading artists of the day who elected him an associate member of the Royal Academy in 1831.

Reverse of Wyon’s medal for Sir John Soane, 1834, showing the Tivoli corner of the Bank of England. British Museum

When the Architects of Great Britain wanted to honour Sir John Soane in 1834 it was to Wyon, described as ‘the most eminent medallist of this country’, that they turned. Rising to the challenge, Wyon produced a boldly sculptural medal which would, they hoped, ‘worthily hand down their respect for the name of Soane … and carry it to the most distant climes.’

It was this growing reputation which secured for Wyon a dream commission in 1833, to model a wax portrait of the young Princess who was heir to the throne.

This early experience served Wyon well when Victoria came to the throne in 1837. Pistrucci, as Chief Medallist, was commissioned to do the Coronation Medal, while Wyon was asked to make a portrait medal of the young Queen to celebrate her official visit to the City of London on 9 November 1837.

The choice of Pistrucci to execute the Coronation medal and the comparison between his and Wyon’s portraits of the Queen proved highly controversial. From March to September 1838 the readers of The Times and the Morning Chronicle were regularly treated to blast and counterblast by Wyon’s and Pistrucci’s supporters. Determined though William Hamilton was in defence of Pistrucci, it was Wyon who benefitted from this controversy. Seen as the champion who had established Britain’s eminence in glyptic art, and elected a full Royal Academician in 1838, he was enormously in demand: for the coinage necessarily, but also for every society with royal patronage, the Goldsmiths’ Company for its hallmarks, and Rowland Hill for his new penny post. Wyon engraved the dies for the embossed pre-paid stationery, and his portrait of the Queen, was used for the Penny Black and its successors for more than 50 years, appearing on almost every letter sent in and from British colonies and dominions around the globe.

What Wyon cared about most, though, was the British coinage. He was always keen to work on large, high value coins, like crowns and five pound pieces, which were prestigious and profitable, but he also valued the copper coinage highly because it was closer to the Roman bronze coins which he admired for their commemorative role, and because by avoiding the shiny and reflective surfaces associated with precious metal it was better able to convey the sculptural qualities of his work. His penny for Victoria’s coinage is a triumph of classical coin design, beautifully modelled to convey the [entirely misleading] impression that the Queen was a classical beauty. Wyon’s friend Richard Sainthill wrote of it, ‘I do not think any engraver could produce a finer head. It has her Majesty’s ease, sweetness, and dignity, with the greatest delicacy of outline, and characteristic truth of nature’, and this high opinion was widely shared.

Constantly ready to innovate, Wyon used the opportunity provided by a new five-pound piece to come up with a new symbolic representation of regal power appropriate to a female British monarch. Victoria is shown as Una, from Edmund Spencer’s The Faerie Queene, kindly but firmly guiding the English/British lion, symbolic of her country and its people.

Under the influence of Prince Albert, who chaired the commission responsible for decorating the new, gothic, Houses of Parliament, Wyon went on to seek medieval sources for a new ‘gothic’ crown and the infamous ‘godless florin’ creating a range of pattern coins which appealed strongly to the collectors’ market.

The Queen as Una, with her lion (from Spencer’s Faerie Queene), 1839

Equally valuable to Wyon were to be the new opportunities opened up by the decision to start awarding campaign medals to members of the British armed forces. There was a precedent for this. Wyon had arrived at the Mint in 1816 just as the production of some 39,000 Waterloo medals, for all those who had taken part in that battle, got underway. But this had been intended by the Duke of Wellington and the government to be a unique reward for a unique victory. The East India Company might and did reward its armed forces, but it was not until the government faced an urgent need to obscure the scale of the British defeat in Afghanistan in the winter of 1841/2, that campaign medals were again struck, and granted by the monarch to all who had taken part in a particular action.

Godless florin, 1848. Royal Mint. Godless because the traditional Fideo Defensor [Defender of the Faith] and Dei Gratia [by God’s grace] are missing

The most controversial of the first group of campaign medals was struck to reward those who had taken part in the victorious if disgraceful campaign known as the First Opium War, waged in order to force China to allow free access to the Chinese market, for what was known by all concerned to be a damaging and addictive drug. Wyon, at Prince Albert’s suggestion, came up with a reverse showing the British lion standing in triumph over the Chinese Dragon. This was approved by the Governor General of India, the Colonial Secretary, Prince Albert and the Queen. But, at the very last moment, the then Prime Minister, Robert Peel, appealed to the Commander in Chief, the Duke of Wellington, and the Foreign Secretary, Lord Aberdeen, for support in persuading the Queen that another design would do less to damage relations with a state with whom, as he put it, we ‘wish to maintain commercial and friendly relations for the future’. The Queen gave way with good grace, but she and Albert still preferred the earlier version as Wyon was pleased to discover when he went to Windsor to deliver gold and silver proofs of the original medal for the royal collection in 1845.

Two versions of the China Medal 1842/7

In a letter dated 26th January 1849 to his friend William Whewell, Master of Trinity College Cambridge, Wyon wrote ‘I can assure you that in the whole course of my life I have never been so much oppressed with public business as of late years owing to the immense number of public medals that have been made for the government. My time and thoughts have been entirely absorbed. The last two thousand [of the China] medals will be completed in a fortnight when I trust to be free to execute my private commissions…’

“Wyon had arrived at the Mint in 1816 just as the production of some 39,000 Waterloo medals, for all those who had taken part in that battle, got underway”

The pressure of work was intense, Wyon’s health was deteriorating and his wife Catherine, who had done so much to support him through difficult times, died on 14 February 1851 after a long and distressing illness. But the pressure continued. A couple of months later, Sainthill found the remaining family in Wyon’s workroom, checking [Punjab] medals ‘and rejecting any not perfectly well struck. And Mr Wyon’s man went off with 2,000 others, in four boxes, to be shipped for India.’

Alongside the demand for new general service medals, to be granted to almost all those who had served in the Army, the Navy and the Army of India over that last half century, there was the excitement of the Great Exhibition of 1851, in which Wyon was closely involved. Prince Albert had sat to Wyon for a medallic portrait in 1840, very soon after his marriage, and the finished result, pairing the Prince with an image of George and the Dragon under his family motto TREU UND FEST was used by him to reward those who had given him outstanding service. It was also a delayed riposte by Wyon to Pistrucci’s much admired George and Dragon for the coinage earlier in the century.

In March 1850, just over a year before the exhibition was due to open, Wyon was called by Prince Albert to Buckingham Palace to be appointed to the committee responsible for the medals intended to reward participants. Wyon went on to organise the international competition to select the artists, and the exhibition of the 129 competition entries at the Royal Society of Arts and was a member of the jury for class XXX [thirty] Sculpture, Models and Plastic Art. Most important he was asked to design, model and execute the obverses of the Council, Prize and Jurors’ medals.

In August 1850 Wyon went to Osborne to obtain sittings from the royal couple. Prince Albert was pleased with the model saying, ‘our compliments, Mr Wyon; you will send us down to posterity in the most favourable manner: you have idealised us as far as was safe’. When Wyon went again to submit a proof of the finished medal he received even higher praise from the Prince: ‘After looking at the busts for some time, the Prince extended a hand, and shook Mr Wyon’s very heartily’ going on to say ‘that the Queen’s bust on the medal is the best portrait ever taken of Her’.

and reverse by his son Leonard

Shortly after this, at the apogee of his success, Wyon’s health finally gave way. He tried leaving the polluted air of London and setting out first to Wales and then Brighton for rest and fresh air, but this time to no good effect. He suffered a stroke in September and died the following month.

His obituaries were fulsome. The Illustrated London News was typical in drawing attention both to his reputation as an artist and to his personal qualities: ‘This distinguished artist possessed a world-wide reputation as a medallist for the number and excellence of the works which he executed … the works of Wyon, will last for ages upon ages’ it predicted, ending on a less formal note ‘as a companion, he was greatly sought by the elite of literary, scientific and artistic circles; and his engaging manners and delightful conversation, no less than his eminent talents, secured for him a very large number of friends.’ The last word belongs to the Queen herself who noted in her diary ‘I grieve to say that the excellent, talented man, Mr Wyon, who modelled the medals, is no longer alive. He was Medallist to the Mint & will be a serious loss.’

William Wyon by Mark Jones will be published by Spink Books in January 2025, and will be available to order via our website, www.spinkbooks.co.uk.

- Inadequate chimneys and the use of sulphuric acid to clean silver exacerbated the pollution caused by coal fire boilers. ↩︎

By Mark Jones