“The raft not only represents a suppressed culture and a forgotten ceremony, it also marks the beginning of a story rivalling the legend of Atlantis: El Dorado, the fabled lost city of gold.”

The reverse of the Colombian 2 Pesos Oro banknote proudly depicts the Balsa Muisca, a votive artefact sometimes referred to as the Golden Raft of El Dorado. To most, this unassuming banknote design might simply portray Colombian heritage. However, the raft not only represents a suppressed culture and a forgotten ceremony, it also marks the beginning of a story rivalling the legend of Atlantis: El Dorado, the fabled lost city of gold.

Revolutionary Design

The 2 Pesos Oro banknote (Standard Catalogue of World Paper Money 413, Banknote Book 948) has a really interesting design. There are subtle yet beautiful elements, earthy tones contrasted by pops of bright colour, and the inclusion of a guñelve 8-pointed star pattern in the border. The pattern, sometimes known as the Star of Arauco, is common in Andean and Mapuche textiles and art and is a nice touch to incorporate into the banknote’s layout.

There are two bolder design choices, namely the portrait of Policarpa Salavarrieta on the obverse, and the Muisca raft on the reverse. Although this banknote initially caught my attention because of its depiction of the Balsa, I became increasingly fascinated by Policarpa Salavarrieta. Nicknamed ‘La Pola’, Policarpa was a spy and messenger for the revolutionary forces during the Spanish Reconquista. She used her position as a seamstress to access working- and upper- class people to pass on intelligence and aid the independence movement (Notable Latin American Women, Jerome Adams, 1995).

In 1817, Policarpa was captured by Spanish authorities, tortured, and executed for treason. There is some debate over her final words (Adams, 1995). Translated to English, the most commonly attributed version is: “Although I am a woman and young, I have more than enough courage to suffer this death and a thousand more”. Her reported defiance in the face of execution is a powerful testament to her legacy as a heroine of independence.

“Though Policarpa Salavarrieta and the Muisca are from completely different aspects of Colombian heritage, both are symbols of the same idea.”

The focus of the 2 Pesos Oro reverse is the Balsa Muisca, an artefact currently housed in the Museo del Oro (Gold Museum) in Bogotá, Colombia. Also known as the Chibcha, the Muisca were an indigenous people of Colombia before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. As a symbol of their civilisation, the Muisca raft is a clear expression of Colombian independence and national identity, making it a significant choice to pair it with the image of Policarpa Salavarrieta. Though they are from completely different aspects of Colombian heritage, both are symbols of the same idea.

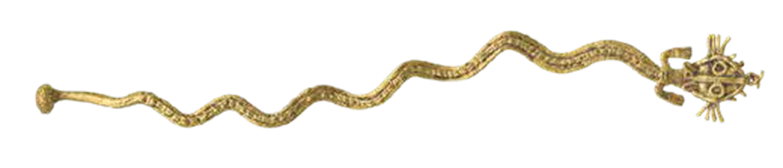

A serpent tunjo, gold, Colombia, 10th-16th century © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The value of gold

The Muisca Raft is described on the Museo del Oro website as being the most recognisable piece in their archaeological collection. Its dimensions are 10.2 cm in width, 19.5 cm in length, and 10.1 cm in height. It was created using a wax casting technique, a common method used by pre-Colombian goldsmiths (Pre-Colombian Metallurgy of South America, Elizabeth P Benson, 1979). The Muisca style is “perhaps the easiest to distinguish”, with the most characteristic object being a tunjo (Benson, 1979, page 43).

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Tunjos are small anthropomorphic or zoomorphic figures made of gold or tumbaga (a gold and copper alloy). They were votive offerings deposited in sacred places such as lakes or caves. Their detailed symbolism offers us valuable insights into Muisca social structure and religious practices. The arrangement of tunjos on a flat base, as seen on the raft, is a distinctive feature of Muisca goldwork. The Balsa is considered one of the best-preserved examples of this and showcases their advanced skills. Tunjos sometimes appear on the collectables Tunjos sometimes appear on the collectables market and their appeal is undeniable. Typically small in size, tunjos demonstrate an intricate craftsmanship that reflects the Muisca’s profound reverence for gold.

One notable type of tunjo is in the form of a snake. These are particularly symbolic offerings to deposit into lakes, as both snakes and lakes are associated with Muisca ancestral mythology. Snakes feature prominently in Muisca creation stories, with one tale describing two snakes emerging from a lake and transforming into a woman and child. The Muisca believed lakes were inhabited by deities in the form of snakes, and the deposited artefacts were intended as offerings to these gods and ancestors.

For Colombia’s pre-Hispanic cultures, gold was not an elite material related to wealth. It held deep spiritual significance, representing the sun, life cycles, and reflecting cosmic natural power. Although it played an important role in both political and religious rituals, it was also used to create everyday objects for members of the community. Another Colombian banknote, from the same 1959- 1986 series as the 2 Pesos Oro, features these in its design. The reverse of the 20 Pesos Oro (Standard Catalogue of World Paper Money 409, Banknote Book 951) depicts other objects from the Museo del Oro, including an illustration of a tunjo. These beautiful objects are more than mere artefacts, they are exquisite examples of the Muisca’s beliefs and their sophisticated metallurgy techniques.

the price of gold

It was this aspect of Muiscan culture that captured the attention of the Spanish. They systematically plundered South America of its precious resources. While several factors contributed to the decline of the Muisca, the role of 16th century Spanish colonialism in its erasure cannot be overstated. Warfare, forced labour, and epidemics caused by European diseases led to a catastrophic decline in the indigenous populations (Luis Fernando Restrepo, The Muisca beyond Melancholy: Literature, Art, and the Colombian State, in Sara Castro-Klaren (ed.), A Companion to Latin American Literature and Culture, 2022, pages 305-322). Land and resources were seized by Spanish invaders, and foreign languages and religion were imposed on indigenous cultures.

Many of the Muiscan objects we have today were only saved from the Spanish because, as part of Muisca ritual belief, they had been deposited in inaccessible places. For example, the raft was discovered in a cave—La Cueva de Los Santos. Many other objects, such as tunjos, have been removed from Lake Guatavita. As a result, these golden artefacts and the lives they represent serve as poignant reminders of a rich cultural heritage that might otherwise have been lost to history.

The ritual and the legend

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Muisca raft is ritual in its purpose. A large central figure, probably depicting a Zipa (a Muisca ruler), distinguishable by his headdress and personal decorations, is surrounded by a group of smaller attendants. These tunjos are attached to a flat, oval-shaped base, meant to resemble a ceremonial raft. It was used as a votive offering and represented a ritual on Lake Guatavita (Ancient South America, Karen Olsen Bruhns, 1994). This ceremony, known to the Spanish as ‘El Dorado’—the Golden Man— was performed by the Muisca to inaugurate a new Zipa. The Zipa was “powdered with gold dust which he washed off himself in the lake waters” (Bruhns, 1994, page 345). Important individuals, like the chiefs and priests depicted around the Zipa on the raft, would then cast gold and emerald offerings into the lake.

The Spanish reacted to accounts of this ceremony with intense interest. Naturally, they were eager to seize gold objects created by the Muisca and use the gold elsewhere. The story of the Golden Man soon morphed into tales of vast quantities of gold at the bottom of a lake in South America, culminating in the legend of a city of gold. El Dorado quickly became a myth of a lost golden city, inspiring many treasure hunters to explore Colombia for this legendary trove. Lake Guatavita became a particular target, with multiple attempts to drain it and excavate the surrounding areas.

The Spanish conquistadors misinterpreted the profound spiritual significance that gold held for the Muisca people. This cultural myopia was not unique to Colombia but was repeated by European invaders across South America. While the Spanish did extract a huge amount of gold, their focus on its monetary value caused them to overlook the true meaning of the ceremony. Paradoxically, the very legend they helped create has endured for centuries, capturing the imagination of countless treasure seekers and inadvertently ensuring the immortality of the Muisca culture they were attempting to subjugate.

a poetic ending

Traditional archaeological studies of Muisca culture have often presented a restricted view of it, simplifying its society to a pyramidal political structure with a unified language and culture (Archaeologies of Early Modern Spanish Colonialism, Berrocal et al, 2016). However, this portrayal is now being challenged by a recent revitalisation movement in modern Muisca communities in Bogotá, who want to reclaim their heritage from external narratives (Luis Fernando Restrepo, 2022). Further supporting this shift, a growing number of archaeologists are reevaluating those traditional interpretations of pre-colonial South America, acknowledging the oversimplification of its rich and diverse societies due to limited material culture and research (Berrocal et al, 2016).

Nevertheless, the allure of El Dorado continues, often overshadowing the deeper spiritual values at the heart of the Muisca people. When faced with beautiful, intricate artefacts such as the Golden Raft, it is impossible not to be astounded by the skilled craftsmanship of so long ago. But as many treasure hunters have learned over the years, for want of a better turn of phrase, all that glitters is not gold.

Edgar Allan Poe’s poem Eldorado poignantly captures the futile pursuit of a lost city of gold. The poem tells of a knight who spends his whole life searching for its untold riches. Now weary and old, the knight asks a shadow where he will find Eldorado, only to be told that the treasure he seeks lies beyond the realm of the living. This literary allusion serves as a powerful metaphor for both the Spanish conquest and the enduring fascination with El Dorado. Poe holds ‘spiritual wealth’ above all else, much like the belief at the heart of the Muisca civilisation. The true legacy of El Dorado is not a city of gold, but a reminder that the most valuable treasure is often intangible.

‘Over the Mountains Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow, Ride, boldly ride,’

The shade replied,—

‘If you seek for Eldorado!’

(The Complete Poems and Stories of Edgar Allan Poe, 1946)

By Olivia Collier