Those who know me are aware that I’ve been collecting and researching for a very long time. Far from seeking distinction within a fraternity of exceedingly clever and accomplished people, some amused at my notaphilic fascinations, I now own up to a variety of errors and miscalculations I have made.

My interests were founded generally in the several faces of Russia and its neighbours from the middle of the nineteenth century to the end of World War Two. You may agree with me that collecting, from accumulation to classification, or taxonomy, is a species of madness, an addiction, yet a healthy one with

smart purposes. That is why I defend the view that well-aimed, purposeful collecting is a specific science.

Certainly, if dozens of well or lesser-known specialists can publish catalogues and books in various fields of paper numismatics, their hard graft and research will come to be regarded as discerning science. That science is now far into its infancy and approaching the degree of maturity evident in the ‘Insider’ and ‘IBNS Journal’. Like greater and more established sciences ‘notaphilic’ study informs the world of select aesthetic and technical matters underlying history and economics. It adds to a greater corpus of understanding.

Dangers to any science include superficiality, weakness of observation and falling prey to commercial requirement. If a study is to search out the ‘where, why and how’ of a phenomenon or event, it is better to avoid the haphazard and develop a consistent method in comparing and recording. In my case the evidence has of necessity been drawn from sources within my economic means.

Let me admit mistakes and successes by illustrating several acquisitions, made in a competitive market. My earlier assumptions about these have sometimes proven incorrect. For example, I live in some anxiety that my background in foreign language and war history may be inadequate. As I illustrate this strangely overprinted Provisional credit note of 1918, I wonder about its authenticity. My first hope was open to correction. Very kindly Mikhail Istomin warned me that not only was this 500 Ruble (adapted for the Sakhalin Province) not listed, but that it was a forgery. I was prepared to argue, as it was firmly overprinted on both sides with the text (in Japanese and Mongolian), as listed for a 1000 Rubles of the 1918 series. This last I’ve noted but not obtained, despite having offered for a recent listed example.

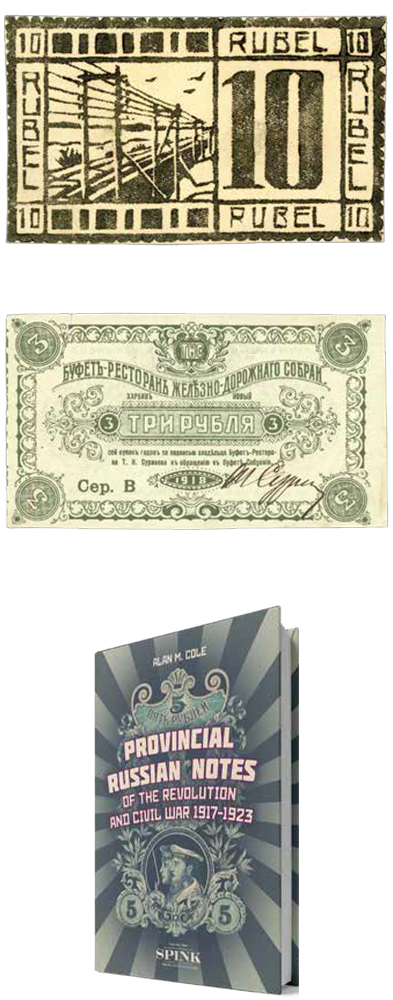

The question of authenticity calls for a distinction between counterfeit and forgery. ‘Counterfeit’ is an overused cover-all term. Some notes can be recognised as counterfeited. One shown here: the 10 Ruble overprint on a 1 Ruble Romanov bill of 1898 is classified under ‘Gulaya Pole’, the temporary stronghold of

Ataman Nestor Makhno in the Kuban region, then in Ukraine, (Ryabchenko R-1356, Vol II; and Istomin Vol.II, pp 303).

Nestor Makhno, traceable on Wikipedia, was a lesser known figure in the revolutionary southwest of Russia. He caused havoc among Red and White contenders for military victory.

It is not known how many Imperial bills and Denikin’s Rostov notes the Makhno brigands

“I accept the caution to be wary of the authenticity of rarer notes.

But the risk may be part of the stimulus of searching.”

(mostly disaffected Cossack cavalrymen) managed to seize. Neither do we know where they were overprinted and in what quantities. It is known however that printing may have occurred in Feodosia, and that a dozen or twenty distinguishable varieties are listed (Istomin), of which that shown is one. If genuine it is extremely rare, which is one good reason for believing this example is not. But is it a counterfeit, reproduced in the 1920s and therefore itself rare? Or is it a forgery done probably in the 1970s for the souvenir market? and consequently not significant? My guess, noticing its poor condition, then acknowledging that the overprint itself is inexact and sketchy, is that it is an example of a scarce counterfeit from Ekaterinoslav about 1919.

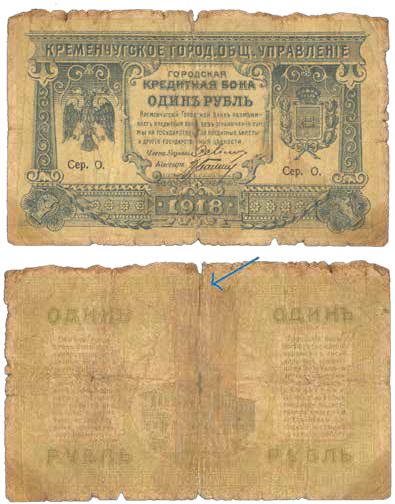

The Imperial note is genuine and well-circulated. Surviving bills in the pockets of fleeing horsemen or local peasants could have numbered only hundreds, even dozens. The original overprinted emissions would have shared the rebellious Ataman’s fate. I accept the caution to be wary of the authenticity of rarer notes. But the risk may be part of the stimulus of searching. That risk alerts us to other collecting hazards. One such is the obvious deterioration of older lesser-known issues, sometimes subject to repair with tapes or hinges. Emergency processes of this kind may ultimately do worse damage to a split or tattered rarity, as in this fragile Kremenchug remnant.

Dealers I have known are usually not dishonest about damage. The need to acquire examples has sometimes led me to overlook attempted repair. Even after careful removal of residues, the conservator cannot conceal residual marks. There are ways to secure damaged notes to survive further handling or display. Graffiti during the time of circulation (signatures and issue numbers) can become a legitimate part of the bill’s working life.

Another tedious habit of earlier collectors and unwary dealers is the addition of pencil graffiti in the margins, to indicate either a catalogue reference number or, worse, the recommended sale price. Even the most carefully attempted erasure can result in unsightly scuffs. Let me not speak of the sin of trimming edges of notes to obviate the fact of edge nicks! Almost as bad is the separation of uncut sheets which, because intact, have a specific printing history to tell.

My classic mistake is to overpay for what is evidently scarce and desirable. This opens the question of how to judge worth. It is often claimed that the worth of a historic piece is a sum the buyer is prepared to pay. Usually, the auction market supports this view. Opinions based on attractiveness or outdated catalogues are less helpful. Historical significance cannot be overlooked and adds value. Dealers of course need to make a profit, to sustain shop-front or online enterprises.

The collector therefore enters something of a competition, either by bargaining or by surprising the seller with superior knowledge.

Seldom have I succeeded in this dubious practice! It does not always pay to play the expert, even if confident of one’s territory.

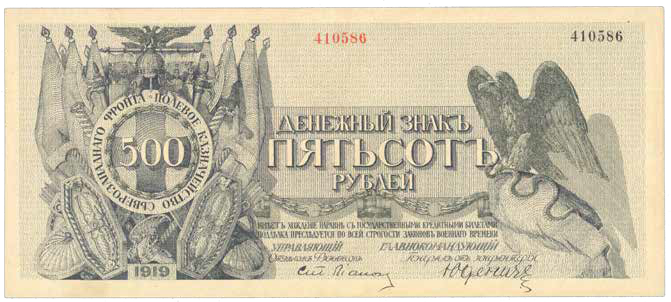

Two singular examples of over-pricing come to mind: the higher values of the General Nikolai Yudenich Northwestern Army series (PS 201-210), which flooded western markets a decade ago; and the attractive trans-Caucasian rail series (PS 593-596) with its bridges, trains and maps. Apart from the rare two top denominations (5000 Rubles seen here), and the ‘A’ series with only three digits, these were released in large bundles (yes, in top condition) also around 2010. Look at this magnificent image!

Similarly, the Yudenich series, of which I show only the scarcer 500 Ruble denomination, has been recovered in bundles. Only some of the ‘A’ and ‘b’ series with three-digit or exceptional serials (in lower values) are of price-worthy interest. An extra trick is to ‘slab’ common notes in order to inflate collectible value, with rare items that may be justifiable.

My best bidding endeavours have frequently failed, leaving me only memories of a much coveted note. After incautious purchases l have later discovered, months after walking off with a currency note (once thought rare), that a hoard has been held back by some rascal in another country and slowly drip-fed into the appropriate online display. A possible moral is: if you don’t pay the price, you don’t get the goods!

At one point I developed a fascination for bills arising from embedded or roaming brigades of political mercenaries, those in particular of the Russian civil wars from 1917. Czech and Slovak legionaries, originally overseen by President Dr Tomasz Mazaryk resisting the Bolshevist uprising in Russia. Such nationalists operated around the new South Russia Republic under the famous Admiral Alexander Kolchak.

Apart from supporting White resistance forces, then occasionally the Reds to whom a few units surrendered, they repaired railroads, transported armaments, extended telegraph and ran social-cultural activities for foreign militia: Poles, Austrians, Hungarians, Germans and possibly French. The paper notes seen are examples with propagandistic and nationalistic elements: vine leaves, spread-wing eagle, Slovak Cross, exclamations of victory. Designs are partially based on a Siberian format familiar to Russian collectors.

One little explored field is the range of motives under which enthusiasts collect and unexpected rivals like train fanatics, POW researchers or those delving into oil history. Any of these and more may search for the very notes I myself seek. Of course, it’s fair competition. From the 1970s we also saw companies developing ‘banknote’ investment folders as an alternative to the stock market. Unfortunately in my view, the investor could own some very important and valuable banknotes and bonds, but never care to visit them, closeted away in foreign company vaults.

A decade or so later, the folio might be ‘executed’ as they say, and sold for ten times the investment price to other grand buyers waiting in the wings. An interested public might never have had the opportunity to see them, much less buy and research them for posterity. Specialists in any field of note collecting can be beaten to the purchase by fanciers in parallel specialisms like military history, currency museums, print and design technicians, schools of engraving, experts in paper manufacture. They may all be looking legitimately for the very pieces you want.

Enthusiasts for Prisoner of War scrip reliant on the Russian section in Campbell (6956-6965) may be intrigued to see these more intensively treated by other cataloguers. Simple but unique in appearance are the lager notes from Krasnaya Rechka, an area north of Irkutsk in Baikalia. Those pictured (R-11145, 11146) are two of several short series of German and other European officers’ and ratings’ camps after 1919 surrenders. Most interesting to the collector are internal lager images of barbed wire and bleak landscapes.

We can imagine the print method of some artistically skilled designers, lino-cutting from their leather belts, then inking with whatever dyes could be found in their stores, and carefully pressing on recycled paper, perhaps from their own notebooks. Due to the tedium of this process and probably rather limited need for exchange, the ‘print-run’ would have amounted only to dozens. Their rarity is obvious.

This micro-economy was tolerated under the eye of less educated guards. The simple layout of apparently primitive tokens yields certain subtleties. The block in which the officers were billeted is marked with a capital letter. Design style is noticeable in a Bauhaus-style art deco. ‘Rubel’ is according to its German spelling. I love these notes, which tell me much that I need to know about internment conditions, though less about the dispositions of the inmates, their yearnings and ultimate fortunes. Nor do I know how eventually these pieces came in such fine condition, virtually unused, into my supplier’s hands.

Provincial Russian Notes of the Revolution and Civil War 1917-1923 by Alan M Cole will be available from Spink Books in September 2024.

Finally, I’ve occasionally enjoyed the boost of acquiring the missing item from a prized group. Many private and commercial notes were issued in the Kharbin district of northeastern China, under Soviet influence after World War One. Madame L. Surinova, a businesswoman of some style, took advantage of the new rail routes through to the port city of Vladivostok. She founded a railcar buffet enterprise, catering for passengers on the Vladivostok to Omsk line. Her buffet service may have enjoyed and employed travelling clients on board or at stations like Irkutsk, Ulan Ude and Kharbin itself.

Of the four values: 1,3,5 and 10 Rubles (R-27307-10), only the signed 3 Ruble note is pictured here. All four however are of the same curled and classical design, issued respectively in claret, dull green, bright blue and mid-brown. I rejoice now to complete the series, dated 1918. Sovietisation was slower in parts of the Far East. Clearly, the Surinova enterprise remained in business, at least until 1922, protected by the international trading environment of northern China.

What I have accumulated, wisely or foolishly, conservated, researched and admired, must eventually go back to the world of interest which will set a seal of importance upon it. It will help to reflect on the agonies of war and the cost of adversarial geopolitics. I much hope that my obscure scrip and much more like it will prove collectively a documentary witness to the early twentieth century political history of Russia. The value of paper notes may fluctuate with the degree of interest in studying them. Their voice however gives them a value to posterity far greater.

By Alan M Cole

References

Campbell, L.K. (1993). Prisoner of War and Concentration Camp Money of the 20th Century. Port Clinton, OH: BNR Press.

Istomin, M.I. (2013). Catalog of Banknotes of the Civil War in Russia, Vol. II. Kharkiv: Golden Pages. pp. 328-332.

Pick, A. (1980). Standard Catalogue of World Paper Money. Krause Publications.

Ryabchenko, P.F., & Butko, V.I. (1999, 2000, 2005). Complete Catalogue of Currency Notes & Bons of Russia & USSR. Kyiv.

a manuscript of Anna Comnena’s Alexiad

The emergence of provenance as a point of interest among collectors has solidified over the past twenty years, almost in tandem with the rise of third-party grading

Commemorative Sestertius of Nero Claudius Drusus, struck by his son, the Emperor Claudius (AD 41-54). From the Carfrae, H.P. Hall and Bunbury Collections, as well as the forthcoming collection of Major Hamish and Mrs Ann Orr-Ewing