THE ORRYSDALE COLLECTION OF DR JOHN FRISSELL CRELLIN

MRCS MHK (1816-1886): COINS, CARD MONEY, AND TOKENS

SPINK LONDON, 25TH SEPTEMBER 2024

As part of Spink’s official Coinex offering this year, the Coin department are delighted to bring you the eminent collection of Manx numismatist, Dr John Frissell Crellin MRCS MHK. Born in Malew on the Isle of Man in 1816, to parents John Christian Crellin and Catherine Mylrea Crellin (née Quayle), he followed in the footsteps of a prominent ancestry, as surgeon, landowner, politician, and collector.

The Crellin family had been esteemed figures in society for many generations on the Isle of Man. The Reverend John Crellin (c.1738-1808) had held the post of both Rector of the Bride, as well as Vicar General, and he was central to assisting in the first translation of the Bible into Manx. It was he who purchased Orrisdale House at Kirk Michael, a property that would become synonymous with the family name.

Reverend Crellin’s son and heir, John (1765-1816) was a key figure in the administration and defence of the island, holding a role as a Member of the House of Keys in 1792 and 1795. He also served as High Bailiff to Ramsey and was both Northern and Southern Deemster. Deemster Crellin sadly perished whilst commanding the Northern Battalion of the Manx volunteers in 1816. He had been in the process of building his home, Beech House, in Castletown when his life was cut short. When the corps was disbanded after the Battle of Waterloo, his wife Charlotte was presented with his colours by the Duke of Atholl.

His son, John Christian, was born in 1787 and went on to serve as a Lieutenant in the 6th Dragoon Guards (Carabineers) and the 4th King’s Own regiment. In 1817 he became an elected Member of the House of Keys, a post which he remained in until his death in the 1840s. He and his wife, Catherine, had several children together, the eldest of which was numismatic luminary, John Frissell Crellin – the collection of whom we will sell this month.

John F Crellin attended King William’s College in Castletown and had planned on taking holy orders when he was a young man. However, a change of heart ensued, and he instead decided to study medicine at St Batholomew’s in London, to become a doctor. He went on to earn a diploma at the Royal College of Surgeons. Although he had been offered a Fellowship there, the death of his father in 1842 prompted Crellin to decline the proposition and instead return to the Isle of Man. He decided to make use of his medical training to treat those living on the island, often the poorest in society for whom he waived a fee.

A year after moving back, Crellin was elected to the House of Keys. It was this appointment that ignited the start of an esteemed political career. The doctor was said to have had an independence of character and a pleasing judgement, climbing the ranks to eventually become deputy-speaker, a position which he held for many years. Author Arthur Moor reminisces about Crellin in his 1901 published work Manx Worthies, Or, Biographies of Notable Manx Men and Women, as being “one of [the House’s] most useful, conscientious, and respected members”.

Crellin married Anne Margaret Parsons on 14th April 1850 in Malew and the couple went on to have four children together: Catherine(1852-Unknown); John Christian (1853-1913); Anne (1853-Unknown); and Charlotte Georgina (1858-1906). The family lived at Orrisdale (Orrysdale) House, in Kirk Michael.

A charming passage in a 1870s edition of The Tourist’s Picturesque Guide to the Isle of Man, paints a picture of the property as a pastoral retreat:

Orrisdale House

“A little farther on is Orrysdale Road, to the left, leading to the peaceful abode of J. F. Crellin, Esq., the oldest member of the present House of Keys. It is a large family mansion, prettily surrounded, and comfortable in the extreme. It is almost enveloped in leaves in the summer season.”

Despite one letter where Crellin notes that “What with the increased price of coal, butchers’ meat, bread, …&c and the potatoes so bad one has to be economical a little where one can”, generally the family appears to have been both happy and financially stable.

The archive of the Isle of Man Museum contains many charming photos of the Crellin daughters and other family members. They appear to have changed outfits and set-ups many times in one day, and despite being characteristically formal, a softness and friendliness of the girls shines through.

Charlotte Georgina Crellin

Miss Crellin

Miss Crellin

As a relatively wealthy Victorian gentleman, Dr Crellin enjoyed many typical leisure pursuits, although these always retained a focus on the Isle of Man and its history. He, like his father (who had been a horticulturalist responsible for introducing the flowering currant tree to the island), treasured the natural world, and many of his days were filled with fishing, planting and birdwatching. His keen interest in ornithology saw him mentioned in Alexander More’s On the Distribution of Birds in Great Britain, During the Nesting Season (1865), as he contributed research on the nesting patterns of eagles, twites, crows, doves, guillemots, and kittiwakes.

Crellin mused on the declining numbers of the Manx Shearwater, which despite once being abundant on the Calf of Man, were now considered by him to be “extirpated by rats”. He also had a penchant for Manx folk songs, having collected sheet music, including a version of ‘The Sheep Under the Snow’ (Ny Kirree fo Niaghtey). Dr Crellin passed on this passion to his daughter Annie, who is remembered as a keen singer of such tunes.

Two years after retiring from the House of Keys, Crellin was commissioned by Governor Loch of the Tynwald Court, to help report upon the antiquities of the island.

Aside from all these pastimes, it was his “lively interest in Manx numismatics” which consolidated his reputation, both on the island and further afield. In 1869, Crellin collaborated with his on-island counterpart, Mr Charles Clay (1801-1893), who hailed from Bredbury, Greater Manchester. Together they put together the definitive work on Manx Coinage: Currency of the Isle of Man, from its earliest appearance to its Assimilation with the British Coinage in 1840.

The volume included sections on Treasure Trove, Tradesmen’s Tokens, banks and Card Money (the latter largely by Crellin and arguably not yet improved upon). Clay doesn’t seem to have shared much in the way of background with John Crellin, other than the fact they were both practicing medical doctors.

He was schooled in Manchester and later practiced there, having been taught medicine at Edinburgh.

He was President of the Manchester Numismatic Society, with a particular interest in American coins, as well as those from the Isle of Man. In medical circles, he is remembered as the father of oophorectomy, the surgical removal of ovaries, having performed the first operation in 1842. His statistics of a 65% survival rate was comparatively impressive – however unnerving that may sound to a modern patient!

Throughout Currency, Clay consistently recognises the work of Crellin, thanking him for his “valuable assistance and cordial cooperation”, as well as the “indefatigable industry and perseverance of my friend […] to whom I am indebted”.

Dr Charles Clay

He notes certain Isle of Man finds as being in the possession of Crellin, who had by way of Treasure Trove, saved these “perfect, or nearly perfect, specimens from the melting pot”.

In 1876, Crellin transcribed an original record from the Seneschal’s office that related to the Brass Coinage struck on the island in 1733. After struggling to finish the research for three years, the article was finally published in an 1880 edition of The Manx Society journal, titled Manx Miscellanies. Crellin’s groundbreaking work, accompanied by an informative preface, provides the reader with three key pieces of information which would go on to inform the understanding of Isle of Man coinages for decades. The three points were the following:

Many 1733 copper pence and halfpennies were struck from metals repurposed from cannons at Castle Rushen – modern analysis has demonstrated this assertion to be true.

Crellin’s maternal great-great-grandfather remembered this happening and was potentially involved in the removal of the cannons from the Castle.

The mint of this 1733 coinage stood on the site occupied by the Bank of Mona in 1880.

Crellin’s discovery helped to prove that the Lords of the Island had the right to coin money without the consent of the British Crown, a move which celebrated an increased level of independence. He references his own collection several times, noting that he possesses specimens of this coinage, five of which are up for auction at Spink this September.

Perhaps owing to his political identity, the article simultaneously promoted a strong prerogative for the Isle of Man’s autonomy. Crellin’s tone regarding his own work is reliably humble, as he appeals to readers for “kindly consideration for any shortcomings or omissions for which [he] may be guilty” and hope that his work be at least acceptable if not interesting. But what he does not waiver on, is his staunch belief that the Isle of Man should be self-governing.

He contends that British Parliament never had any right to introduce legislature that would affect the island without the consent of Manx law makers, relating to coinage or other issues. In powerful words, Crellin sees the legitimisation of the 1733 coinage, as a signal to quash wider arguments. These coins were made on the Isle of Man, using Manx metal and this fact should be admired and celebrated. Undoubtably his was an incredibly valuable contribution, not only to Manx coinage, but also the history and identity of Mona’s Isle.

In setting up his discussion of how the Isle of Man pence and halfpence were struck, Crellin vigorously professes: “I have yet to learn that the Manx nation are so ill conducted as to require the Parliaments of two countries to establish and keep order among them […] On the contrary, I believe that there are not a more loyal and well conducted people on the face on the globe […] small though [the Island] be, I look upon it as one of the brightest jewels in our Sovereign’s Crown.”

Eventually, years of ill health caught up with him and in 1886, Dr John Frissell Crellin died at the age of seventy. He was buried a month later at Kirk Michael Churchyard. Spink are privileged to have been entrusted with Dr Crellin’s collection which comprises not only an impressive array of Manx pieces, but also British, World and Ancient. Crellin formed his collection in a surprisingly short span of years. Much of the important material was put together between 1867 and 1869, just before the publication of Clay’s volume. A small amount was added outside of this period, by Crellin himself or his descendants, which explains coins such as the Edward VII maundy money or some of the smaller American denominations.

Such an intact and unrecorded collection, barely touched for 150 years is an indulgence for collectors and cataloguers alike, especially when they come accompanied by impressive provenance backed up by Crellin’s own paperwork including letters, coin envelopes and catalogue lists (some offered alongside lots in this auction). It originally comprised some 1700 items and has been passed down the male line ever since Crellin’s death. The family had enquired about a sale with Spink, both in 1912 and 1966, but it appears no such arrangement occurred. There have since been claims from the Manx Museum, regarding National Importance of field finds, and (bar a couple of Victorian half sovereigns and a Portuguese ½ Escudo) the rest of the gold was sold in 1933 at a time of deep recession.

The ‘jewels’ of the collection (to use Crellin’s own phrase) have to be the run of Isle of Man coins. The collection tracks the coinage of the island from the patterns issued in 1723 to the last legal tender struck in 1839 bearing the portrait of Victoria, offering a breadth and completeness rarely encountered on the open market and testament to Crellin’s collecting achievement.

Examples range from those more commonly encountered to the scarcest known specimens, all in exemplary and highly desirable condition. The earliest history of Manx coinage is largely unknown, a field where fact and fiction have become intertwined. However, it’s widely acknowledged that it was marred by recurring shortages, which led to a habit of invention as well as multiple issuers. The first legal tender of the island was that of John Murrey in 1668, followed in 1709 by the crudely cast copper coinage of The Earl of Derby.

Some written accounts of the series frequently advance directly to the coinage of 1733. However, this overlooks perhaps the scarcest and most intriguing coins: those struck in 1723. It is here that Crellin’s collection begins with an astounding four examples.

This series was never sanctioned by law to circulate as legal tender and the coins are therefore understood to have been struck as patterns pending approval for island use. In Clay’s 1840 publication, he notes their beauty and scarcity as well as being ‘a great step in advance of numismatic excellence’. It is therefore unsurprising that Crellin was drawn to this series and, to quote Clay further, ‘at all events, these coins are only known as pattern pieces, which are greatly to be prized when once in the collector’s possession’.

Perhaps the most desirable is the largest denomination, the Silver Pattern Penny (estimate £2,000-£3,000). Although this is commonly a series often encountered with softness, this example is exemplary in its extremely fine detail to the devices and pleasing lustre.

The last comparable example sold through these rooms was in June 2006 as part of the Hilary F. Guard Collection of Manx Related Items [lot 476]. Despite the sizeable nature of that collection, it did not include any Halfpennies.

The Crellin Collection now affords collectors three opportunities to acquire this denomination: two examples in silver, estimated at £1,000-£1,500 respectively, and an extremely fine copper example (estimate £600-£800).

A further highlight is a near uncirculated Penny of 1733, a condition not commonly seen due to the extensive circulation this series saw because of the relatively small amount issued. Clay remarks this series to be ‘the most beautiful coinage ever circulated on the island’, and arguably this coin was also a key piece for Crellin due to his great personal interest in the series. Additionally, the gem of the Second Duke of Atholl series is certainly a Proof Silver Penny of 1758 (estimate £500-£700) in handsomely extremely fine condition.

Attention should also be given to the Bank of Douglas series of 1811. The start of the nineteenth century was again a time of currency shortages on the Isle of Man. Individual bankers, merchants, and businesses therefore crafted their own; the finest being those designed by T. Halliday for Littler, Dove & Co of the Douglas Bank.

Five denominations were struck: a Five Shillings, Halfcrown, Shilling, Penny, and Halfpenny, all of which are present in Dr Crellin’s cabinet. A Five Shillings estimated at £2,000-£2,500, offers collectors the chance to add a handsomely brilliant and uncirculated example to their very own cabinet.

In terms of the rest of the collection, there is a delightful run of English hammered and milled. Chief among which is the Second Coinage Halfcrown of James I (estimated £2,500-£3,000), one of the rarest denominations in the Jacobean run with only a handful known. Such specimens have graced the very best collector’s cabinets, including Norweb, Bagnall, and Lingford.

Now the Crellin example seeks a new home. Another rare, hammered treasure in the collection is the 1601 Elizabeth I Halfcrown (estimated £1,200-

£1,600). Although lightly stressed, the flan is complete and toned, a very fine example which sets it above several other examples seen at auction in recent times.

Other Medieval delights include a London Groat of Richard III, which despite being characteristically clipped, has an incredibly detailed portrait, is toned in petrol hues (estimated £1,500-£1,800), as well as a Philip and Mary 1554 Shilling, richly cabinet toned and scarce in such a collectable grade (estimated £1,000-£1,300).

Crellin’s keen eye for the unusual shines through with the milled especially, as there are curiosities galore. Aside from Victorian toy money and a spectacular mis-strike of a George IV Penny, there are several sumptuous scarcities available.

The collection boasts a 1693 Corbet Issue of a William and Mary Copper Farthing – of the highest rarity (estimated £2,000-£3,000), and an 1812 Pattern Ninepence Token by Thomas Wyon Jnr, near extremely fine and extremely rare (estimated £1,300-£1,500).

Arguably the most important and definitive part of the collection, comes in the form of Crellin’s unprecedented series of Manx Card Money.

It is the most complete collection ever formed, and likely will never be bettered. Many of the cards offered here are the exact specimens used as illustrated examples in Clay’s chapter on card money, which he admits would not have been half as comprehensive without the “help of J. F. Crellin”.

The majority of the card types have never been available on the open market; some have never been seen since their report – or even ever before.

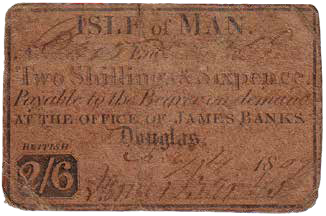

2 Shillings and Sixpence, James Banks

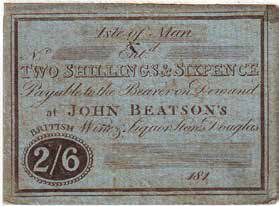

2 Shillings and Sixpence, John Beatson

5 Shillings, John Beatson

The jewel of this section must be the card of 2 Shillings and Sixpence, issued by James Banks on 14th February 1807 (estimated £700-900). It is an unrecorded value of this type and is quite possibly now unique. Other exceptional rarities include cards for which had been recorded but previously had no extant examples known: Unissued 2/6 from John Beatson and Thomas Brew; 5 Shillings from John Beatson and Edward Gawne; Sixpence from Daniel Cowley and 3 Shillings from James Cosnahan. For collectors of card money, this collection gives answers to the many questions and gaps that previously plagued this incredibly short era of currency (1805-1817). Nearly everything we know about Manx Card Money comes from Currency of the Isle of Man (1869). The class and pedigree of this collection is staggering, and Spink is privileged to be able to share it with collectors.

5 Shillings, Edward Gawne

We are delighted to showcase the collection of Crellin, who it is no exaggeration to call, one of the founding fathers of Manx numismatics.

A quintessential Victorian gentleman who fostered many interests, scientific, cultural and natural, but always kept his love of the Isle of Man, and his respect for its identity as self-governing dependency at the forefront of his mind. Crellin was not simply a numismatist, but he was a collector that was connected in every way to his subject and his finds.

Stored in beech wood cabinets lined with green velvet for over a century, this ‘triskelion’ collection affords an extraordinary and rare window into the earliest chronicles of recorded currency for ‘Mona’s Isle’.

By Ella Mackenzie

The Orrysdale Collection of Dr John Frissell Crellin MRCS MHK (1816-1886): Coins, Card Money and Tokens, closes on 25th September 2024. For any questions regarding lots please contact Ella Mackenzie, [email protected], 020 7563 4016.

R-6407 or Pick 1224

“What I have accumulated, wisely or foolishly, conservated, researched and admired, must eventually go back to the world of interest which will set a seal of importance upon it”

R-1356