THE ADVENTURES OF PRIVATE EDWARD BUCK

For most medal collectors, there is normally one particular medal or action that for some reason speaks louder than others. For some it might be a famous action like the Charge of the Light Brigade or the Defence of Legations. Other collectors may focus on one campaign, medal or gallantry award that sparked an interest. Most of you who I have been fortunate enough to meet over the years – or who have been unfortunate enough to sit through a presentation which I have delivered – will know by now that my personal focus is upon awards to the 2nd (Queen’s) Regiment of Foot, latterly The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. Having grown up in the corner of the county and heard stories of relatives who had served (and fallen) with the unit, it was an easy decision when I embarked upon my own collecting journey.

Since its being raised upon Putney Heath in 1661 as ‘The Tangier Regiment’, the first use of the unit was to guard the garrison of Tangier, which was acquired as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza during her marriage to Charles II.

Having served in numerous campaigns, it was however not until the First Afghan War of 1839 that all ranks of the Regiment were to earn any medallic rewards for their campaign. The unit had shared widely in the bloody campaigns of the Peninsula Wars – with even a small number of the unit present for the naval action of the Glorious First of June 1794 – but were not present for the Battle of Waterloo. As you will perhaps know that famous day in the summer of 1815 (which also happens to be my wedding anniversary!) was the first action for which every man on the field, without regard for their rank, earned the same medal with his details inscribed upon the rim. It was a great shame that it took the best part of four decades for Queen Victoria to command the Duke of Wellington to institute what became the respective Military & Naval Military General Service Medals in 1848. So, few of the veterans lived to claim their richly deserved awards and it is no surprise these medals command the interest and prices that they do. The 2nd Foot for example earned just a shade over 150 Military General Service Medals, despite several thousand serving the unit in the campaigns.

For this reason, the Ghuznee Medal 1839 is the first medal earned by the Regiment and one which has always held great significance in my own opinion. The casus belli behind the campaign and re-instatement of the Shah Duranni were one of particular note at present, that being the fears of the possible Russian influence, invasion and conquest of British interests during what was coined ‘The Great Game’. Dost Mohammed had to be deposed and a joint British, Indian and Sikh Army was formed and landed to take the great fortress on the high plains of Ghuznee. With a sapping march of hundreds of miles, the imposing fortress was stormed and taken in the early hours of 23rd July 1839, with the 2nd Foot having the great honour of leading the storming party. They were even granted a Battle Honour to carry on the Colours for their efforts.

At this point I should perhaps introduce Edward Buck, a gallant member of the Regiment. Our protagonist was born at Itteringham in rural Norfolk in February 1814. He enlisted into the 2nd Foot at Norfolk for unlimited service at Norfolk in September 1834 with a bounty of £3. At this stage the young man was listed as a single labourer who was unable to read or write, for which reason he signed on with his mark being an ‘X’.

Buck had endured the searing Afghan summer and the advance up to Ghuznee, when he was a member of the Grenadier Company. He shared in the storming of the fortress, latterly also being present in November for the further sharp action during the storming of Khelat in November 1839. Thus, it was he was rewarded with the medal for Ghuznee with his comrades from the unit. In total around 8,000 medals were struck at Calcutta for the total force which participated in the conflict.

In the years which followed, Buck was promoted Corporal in September 1845 but found himself tried by Court Martial in November 1847 for drunkenness. The punishment appears harsh today, being reduced to Private and sentenced to 40 days imprisonment with hard labour. He did his time and returned to the ranks.

As the years rolled by, many veterans of this earlier campaign either took their discharge, moved on to other units or were released on account of illness and infirmity on account of the climates in which they served. This didn’t seem to count Buck out, for he was one of a very small band of soldiers who were embarked for further campaign service in South Africa in the summer of 1851 for the 8th Xhosa War.

Six service Companies of the unit embarked from Ireland for the Cape in June 1851. Setting out in three contingents, many of the men experienced harrowing journeys, not least those embarked in the Birkenhead; the smallest contingent in the Sumner experienced a fire and did not reach East London until September 1851.

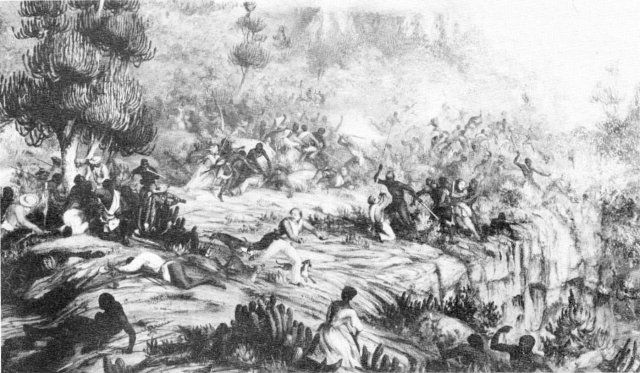

In early September, 180 officers and men with supporting detachments from other regiments were sent to patrol the Committee’s Hill. Finding themselves confronted by a large body of warriors, they were forced to extend in skirmishing order and the whole patrol was gradually brought into action. A heavy fusillade from the enemy concealed in clumps of trees and the bush caused numerous casualties, including three mortally wounded, the men eventually being forced to withdraw.

“He did his time and returned to the ranks”

Our man was one of those in these actions. Within a week, they found themselves sweeping along the line of the Fish River, attempting to clear out the rebels who were encamped and massing all around. The most notable events were what became coined the ‘Battle of Fish River’ on 9th September 1851. Two Companies – including Buck with the Grenadiers – under Captain Oldham plus some local Levies descended into the bush. They found themselves heavily outnumbered, being cut off, and a scene of sheer terror began. Captain Oldham together with 24 men was killed, with up to another 40 suffering dangerous wounds. In the desperate fighting which followed, it took reinforcements of the 6th Regiment coming to their aid before they could be extracted.

“Within a week, they found themselves sweeping along the line of the Fish River, attempting to clear out the rebels who were encamped and massing all around”

Battle of Fish River by Thomas Baines

Buck perhaps had the luckiest escape of all, for the Surgeon reported that he had to be treated for ‘…13 gunshot and assegai wounds’ and an amusing story was reported by The Cheltenham Looker-On newspaper back home soon after:

‘When asked by the Doctor if he was badly wounded, the man, with a look full of good humour, showed one wound and asked if that was a bad one, to which the Doctor replied “No, that’s nothing!”. In like manner did Buck show all his wounds till he came to the last, which was very painful and asked if that was dangerous. The Doctor’s reply was “No, my man, you are all right.”

“Then go to someone else who more urgently wants you!” was the reply.’

That perhaps best sums up the fine principles of the hard-campaigning Victorian soldier. So severe were his wounds that Buck had to be discharged from the British Army once he recovered in September 1852. He was rated as a ‘…willing and courageous soldier’ when released. Returning to his native Norfolk, he died in the same village in which he was born in July 1871.

Upon studying the published Medal Rolls for the two campaigns in which he served, it appears Buck was one of just a dozen or so Officers or Men who earned the campaign medals for both Ghuznee and South Africa. Having consulted other specialists in the field, this would appear to be the only extant pair, with several others single medals only appearing.

His Ghuznee 1839 Medal has a rather ornate replaced silver ball suspension (the original suspension is rather weak, and they are often replaced) and is engraved to the reverse ‘E. Buck 828 Queens’. The South Africa 1834-53 Medal is officially impressed ‘Edwd. Buck, 2nd Regt’.

The field of studying, researching and collecting military medals is one which I feel opens so many interesting doors and avenues down which one might wander. I hope that you might reflect upon the items in your collection, for which you are the custodian. The journey the recipient and their medals have might gone upon in the time since they were awarded is one which I feel makes this subject a truly enduring and evolving one.

By Marcus Budgen