By Dr. Kevin Clancy

Elizabeth II died a little over two years ago and, in her passing, many at the time rightly saw the end of an era. She embodied in her duty and values a sense of British identity, and her image looking out from banknotes or struck into the millions of coins issued during her long reign became an abiding visual presence and a symbolic constant in a changing world.

“She embodied in her duty and values a sense of British identity, and her image looking out from banknotes or struck into the millions of coins issued during her long reign became an abiding visual presence and a symbolic constant in a changing world”

Portrait of Elizabeth II by Mary Gillick

Her coinage portrait was updated from time to time but in format it reflected a design approach not markedly different from that used on Roman coins 2000 years ago. This timelessness, however, masks a period of considerable disruption during which the coinage of Britain was subjected to major reform and had to withstand existential threats on more than one occasion. Looked at over the 70 years of her reign, the coinage has shown itself to be resilient, but it has not emerged unscathed from the forces of modernisation and technological progress.

Her accession came just seven years after the end of the Second World War. The devastation wreaked by this conflict impacted directly on the British coinage through the abandonment of silver as an alloy for circulating coins from 1947. The mountain of debt the nation built up had to be repaid, and the 500 alloy silver that remained in circulation was gradually withdrawn to be melted down as a means of achieving this, leading to the use of cupro-nickel from then on. When Elizabeth II’s first circulating coins were issued on the eve of her Coronation in June 1953 they would be the first of any British monarch to contain no element of precious metal. Gold coins were produced, the 1953 gold set being extremely rare, and coins of the Royal Maundy continued to be made in sterling silver, but the ordinary circulating coinage was entirely base metal, its token status more firmly embedded than ever.

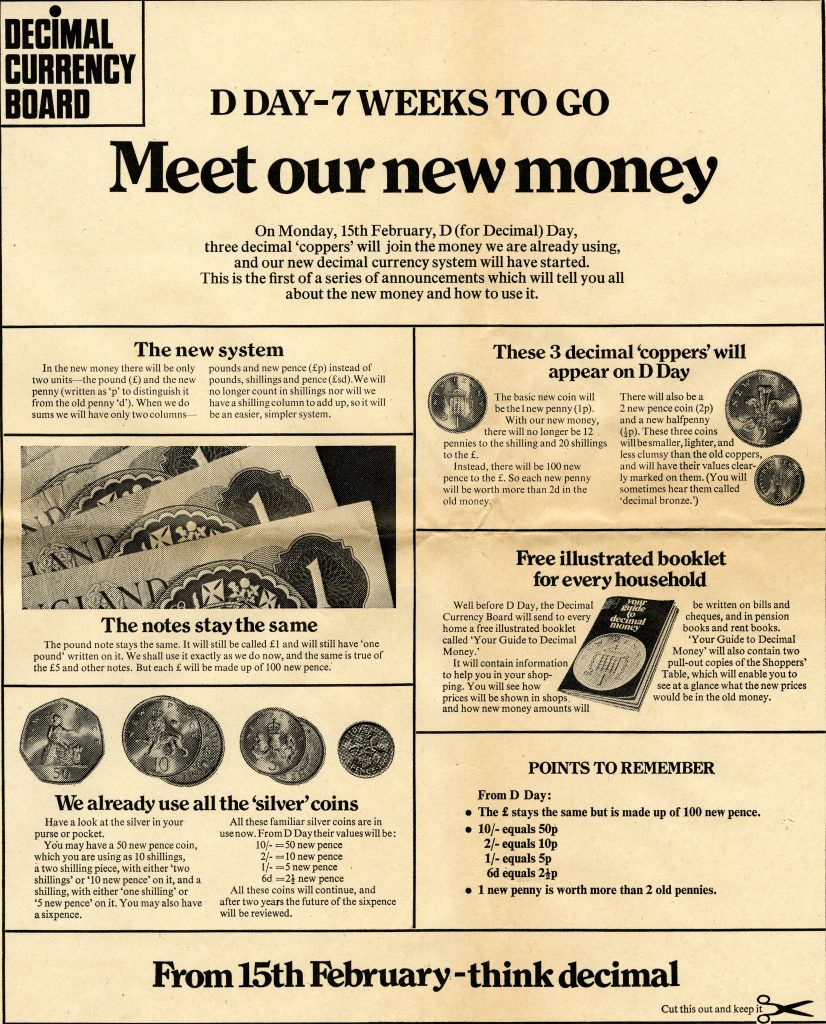

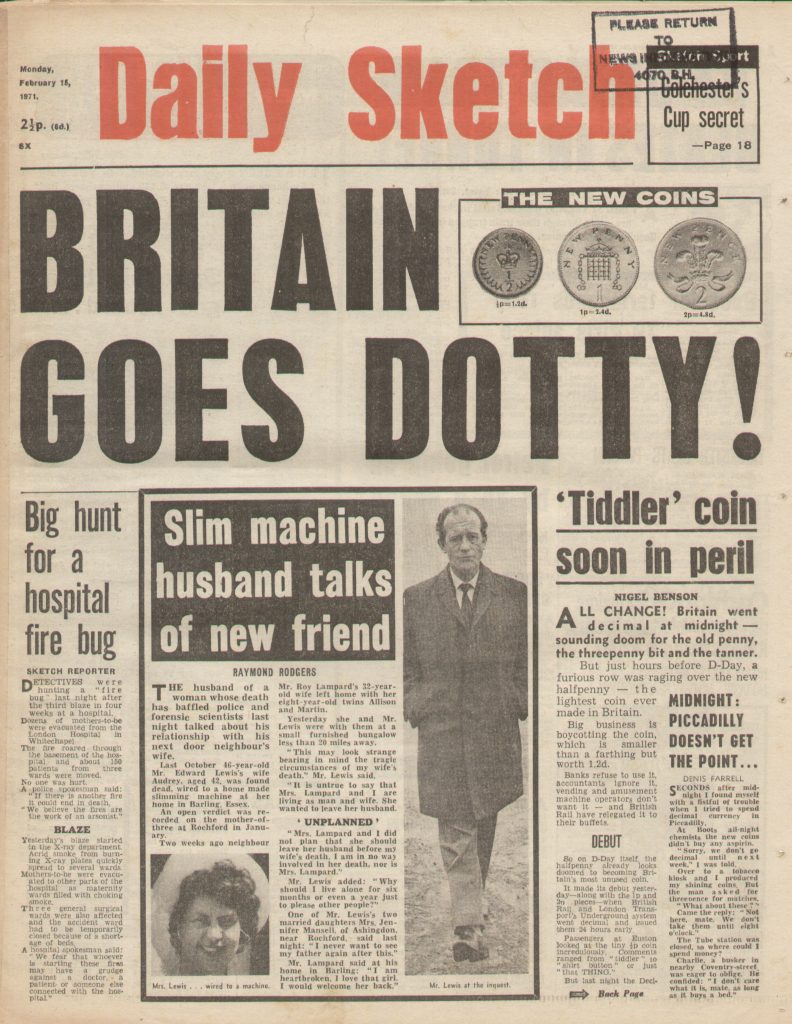

The currency system itself, though, remained intact, or at least for a period of time. The nation’s money was still made up of 12 pennies to a shilling and 20 shillings to a pound, meaning a pound contained 240 pennies. Calculations were carried out across three columns, pounds, shillings and pence, successive generations of school children having to wrap their heads around its complexities. But the forces of modernity had the system in its sights, and after a number of current and former colonies and nation states – notably India, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand – announced they were going decimal in the late 1950s the pressure for Britain to follow suit became irresistible. This would be the first existential threat to the coinage during Elizabeth II’s reign. A thousand years of tradition was to be swept away, and the government had genuine concerns that a change of such magnitude would be met with widespread hostility. It consequently embarked upon one of the most all-encompassing publicity campaigns ever visited upon the population of Britain. A pamphlet explaining the changeover was posted through every door in the country and conversion charts were prominently displayed in banks and post offices, and formed the basis of card games as well as being printed on all manner of different media. As that other D-Day approached, Decimal Day, 15th February 1971, television programmes and newspapers joined the barrage of publicity directed at informing and allaying the anxieties of the nation. When the day itself came, though, there was no rioting in the streets, the fabric of Britain was not irreversibly damaged and those who emotionally clung to the old system became in time as irrelevant as flat-earthers.

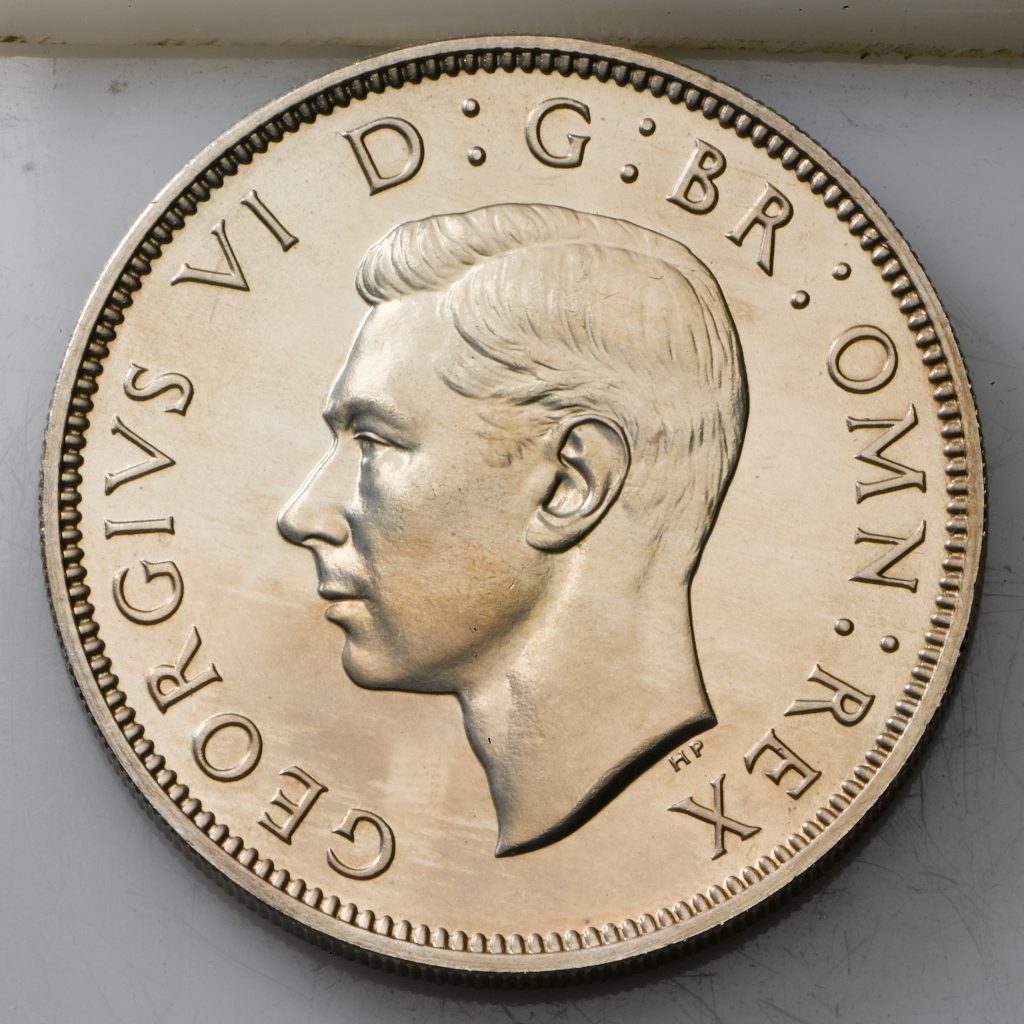

1950 florin.

An extended period of transition was provided for in the changeover, aspects of which were still being played out into the 1990s. Florins and shillings, which had been redenominated as ten pence and five pence coins respectively, were removed from circulation in 1993, the consequence of a change in size of the initial decimal ten and five pence pieces. This provided an unlooked-for moment of numismatic significance in making Elizabeth II, almost certainly, the only monarch to have coins bearing her effigy alone in active circulation. The transition also embraced the sixpence, which had a brief new lease of life as a two and half pence coin in the 1970’s while the halfpenny did not long survive into the decimal era, succumbing to inflationary pressures in 1984. Another aspect of the inexorable increase in prices, specifically with respect to raw materials, propelled the coinage into a further retreat from any sense of intrinsic value. During the 1980s the cost of bronze in one and two pence pieces started to make them uneconomic to produce, the response to which was to make them out of copper-plated steel from 1992, and 20 years later the same fate befell the five and ten pence coins (although this time cupro-nickel was replaced with nickel-plated steel).

These developments partly reflected a period of transition from one currency system to another and partly a natural evolution as the coinage responded to the prevailing economic forces. A feature decimal coins could not reproduce was the familiarity and longevity that generated nicknames, such as tanner and bob. A misguided media-inspired effort to force the name ‘the Thatcher’ onto the one-pound coins produced from 1983 fell on an unreceptive British audience, missing the central point that such terms are by their nature organic.

At the beginning of Elizabeth II’s reign, coins used by over 100 million of the earth’s population, covering about 13 million square miles of the planet’s surface, required changing to feature her portrait. Through the following 70 years the continuous mass production of banknotes, coins and postage stamps mean her image must surely be ranked as the most printed and struck in history. A reasonably significant contribution to these numbers was the extended British family of nations of which she was head of state. Some following independence chose new symbols and individuals to appear on their currencies, but the coinages of Cananda, Australia and New Zealand continued to carry her portrait until the end.

If decimalisation could be seen as a home-grown threat to the coinage, albeit strongly influenced by international trends, the prospect of the Euro was a challenge with its origins quite firmly grounded in Europe. Through the 1990s there was growing pressure for Britain to join the single currency. Under the chancellorship of Norman Lamont sterling tracked the European Exchange Rate Mechanism and when the coinage element of the single currency was being designed Britain, as a member of the European Union, played its role in commissioning artwork. As matters transpired, Britain declined the invitation to join the single currency when it was introduced in 1999 but, for those countries that did, it meant the end of their national systems of coins and banknotes, the franc and lira, the mark and the peseta amongst others being abolished. Sterling remained, and alongside the production of British coins at the Royal Mint there was at the time the somewhat incongruous sight of Euro cents being struck for Ireland.

Coins have been issued for special occasions for centuries but a notable way in which the British coinage changed during the reign of Elizabeth II was the increase in the number of commemorative coins, particularly in the last 30 years. The occasional releases to mark Elizabeth II’s Coronation in 1953 and the death of Winston Churchill in 1965 gave way from the 1990s to multiple issues every year and, following the extensive programme for the London 2012 Olympic Games, the rate further advanced. This trend met an undoubted domestic and international demand and, as a means of celebrating modern British culture, the coinage has taken on themes such as literature, music and science, that have broadened its appeal to new audiences.

Almost coincident with the rise of the commemorative coin market has been that of the trade in bullion coins. In light of the popularity of one ounce gold coins, such as the Krugerrand, Britain sought to establish a presence from 1987 with the Britannia range and this, in turn, has led to a sizable increase in the numbers of precious metal coins emanating from the Royal Mint. The desire for coins in gold and silver in ever-increasing quantities has led to the exotic sight of kilos of gold being made, worth tens of thousands of pounds in intrinsic value alone.

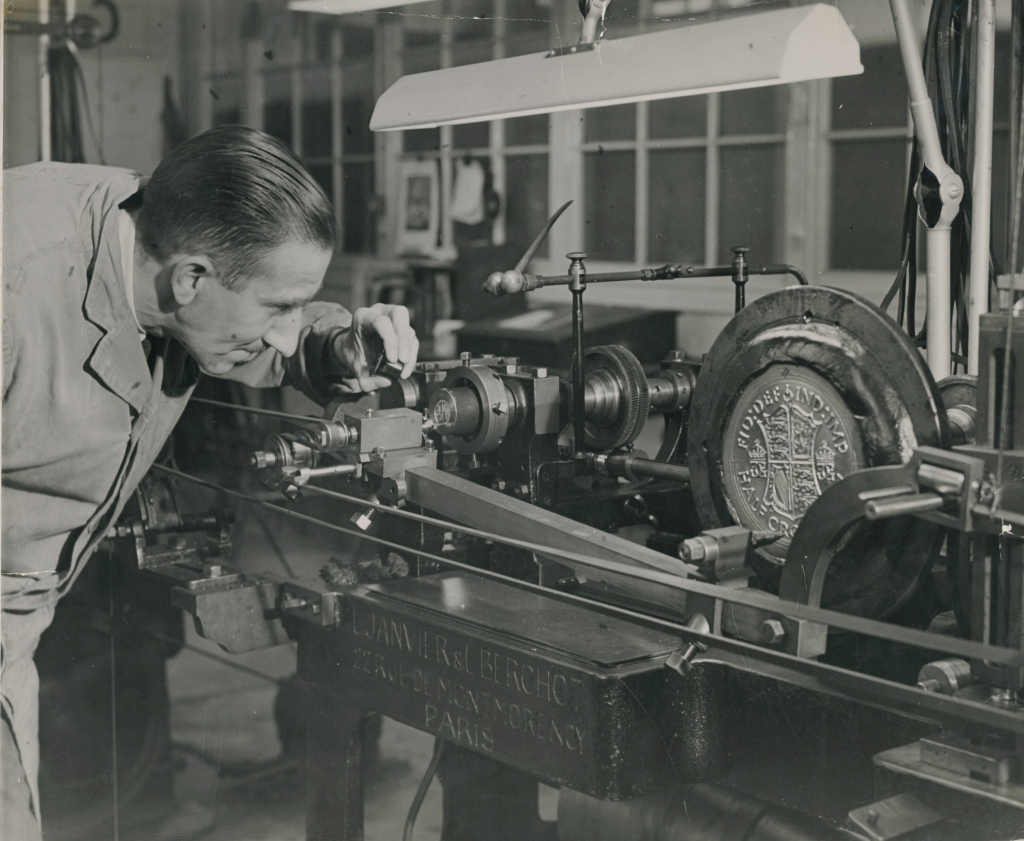

Advances in technology perhaps more than any other single factor have been the most defining force of change to the coinage during the reign of the late Queen. These have come in two principal forms covering manufacture and usage. At the start of the 1990s the technology used to make the tooling in the coin production process was in origin and design nineteenth century. Three-dimensional pantographs built by the French company Janvier, some approaching their 100th birthday, sat at the heart of this process. It typically took several hours to cut a reduction punch using these machines and the nickel-faced electrotypes mounted on them would take a few days to produce. This mechanical process therefore took about a week to generate the first in the required sequence of master coinage tools. Then in the 1990s computer-controlled scanners were introduced which negated the need for making the electrotypes and at the same time programmable cutting machines removed the need for the reducing machine. Within the last decade this innovation was itself replaced by tools being cut using lasers based on artwork generated by three-dimensional design software, which does not require the preparation of a physical model at all. The digitisation of the tool-making process has, as a result, massively reduced the time involved and required coin designers at the Royal Mint to retrain from being engravers in metal to designers on-screen.

The other aspect of how advances in technology have impacted the coinage relates to usage and the advent of digital forms of payment. For many years credit cards, like banknotes before them, did not threaten a precipitous demise in use of cash but little by little an erosion was taking place. Looking at usage over the course of the 70 years of the late Queen’s reign there is a discernible trend, but this was accelerated by the Coronavirus pandemic and also by the extension of contactless payments for smaller amounts. Today no self-respecting teenager would leave home without a mobile phone which doubles as a means of payment as well as the countless other functions it performs. An additional factor must be the post-millennial generation becoming wage earners – the generation which grew up with computers as a basic necessity of life, and in this digital reality they absorbed much less of an emotional let alone functional connection with cash. Surveys by the Treasury and other bodies reveal that many millions of people in Britain still regularly use coins and banknotes, but the trend of decline is a reality and is something that was never a serious consideration on Elizabeth II’s accession in February 1952.

In a book about the redesign of the coinage in 2008, Sir Christopher Frayling wrote the following.

‘A well-known designer said to me recently ‘everyone has three things in their pocket or bag: keys, mobile phones and coins. Keys have remained much the same for hundreds of years, mobile phones are redesigned every month, while coins are somewhere between the two – nearer keys than phones.’

This probably remains broadly true with respect to design, but over the course of the last 30 years the presence of coins in our pockets and bags has almost certainly declined. In the 2000-year history of coinage in Britain, the reign of Elizabeth II will be remembered as exceptional. It was witness to serious threats, major changes of design and function and, most importantly, to an advancement in technology that has led to a seemingly irreversible shift in behaviour away from the mass use of physical currency.

Dr Kevin Clancy FSA

Director of the Royal Mint Museum

Dr Kevin Clancy is a historian who, over the last 30 years, has written and lectured extensively on the history of the Royal Mint and the British coinage. He has been Director of the Royal Mint Museum since 2003, playing a central role in shaping the future of the Museum as a charity through its education, publication and exhibition programmes, including the creation of a permanent exhibition on the history of the Royal Mint at the Tower of London and at the Royal Mint Experience. His publications include Designing Change (2008), A History of the Sovereign: chief coin of the world (2015), The Royal Mint: an illustrated history (second edition, 2016) and Objects of War: currency in a time of conflict (2018). He has edited books on the history of Britannia (2016), the decimalisation of Britain’s currency (2021) and the library of Sarah Sophia Banks (2023). Since 2003 he has been Secretary to the Royal Mint Advisory Committee on the design of United Kingdom coins, official medals and seals. Between 2016 and 2021 he served as President of the British Numismatic Society.

By Dr. Kevin Clancy