PART 3 FROM JAMES I TO JAMES V

“He also issued gold coins which he named the demy and the half-demy, based on the English half- and quarter-noble and approximately equal in size, though of slightly reduced fineness”

Introduction

This article continues the story of Scottish money with a survey of the intriguing coin is- sues of the first five Jameses, starting with James I who succeeded Robert III as king in 1406.

James I (1406-1437) pays another ransom to the English

James I was the third son of Robert III, one of his brothers having died in infancy while the eldest died in suspicious circumstances in 1402 after being detained by his uncle, Robert, Duke of Albany. The latter had been regent to Robert III and was one of the most powerful members of the Scottish royal family. James, with his entourage, had fled the country, aged 11, been captured by the English and then confined to a series of English castles includ- ing relatively comfortable Windsor Castle and the distinctly less appealing Tower of London. In all he was in English captivity for 18 years and, unsurprisingly, his uncle acted as regent in his absence, until the Duke’s death in 1420 when he was succeeded by his son Murdoch.

Yet another hefty ransom was eventuallyVpaid for James’s release, comprising the huge sum of £40,000 English pounds (not, it should be noted, devalued Scottish pounds). It is possible a small amount of this was paid with silver mined after 1424 in Tyndrum in the Highlands but most was also paid from increased – and thus unpopular – taxes paid by the major landowners. The ransom appears not to have been paid in full, however.

James I met a premature end when, after alienating too many Scottish nobles, heVwas assassinated in Perth in February 1437 by a cabal including Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl. His wife Joan was wounded but escaped along with his infant son James who survived to continue the Stewart dynasty.

Billon makes its first appearance

James I increased the value of the groat from 4d to 6d Scots but at the same time issued a much debased “silver” penny called a billon, a term used for an alloy of a base metal, usually copper, and silver. The silver content was generally below 50% of the total and numerous billons were is- sued by James and his successors between 1424 and 1603, with varying levels of silver content.

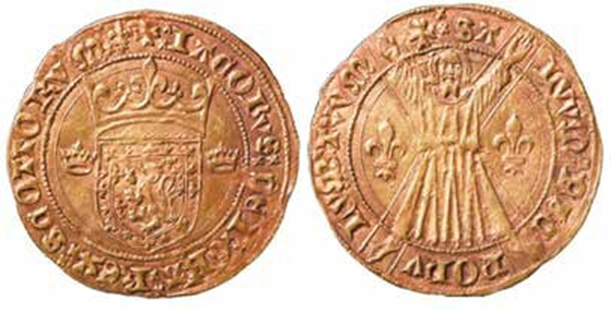

He also issued gold coins which he named the demy and the half-demy, based on the English half- and quarter-noble and approximately equal in size, though of slightly reduced fineness. They equated to 9s and 4s 6d Scots. These should be added to the lengthening list of names for Scottish coins, so far including pennies, groats, nobles and lions.

James II (1437-1460)

James II was seven when he was crowned king of Scotland. He was married at 18 to the 15-years- old Mary of Guelders (a duchy mostly in eastern Netherlands but named after the German town of Geldern). Between them they had seven chil- dren, six of whom survived to adulthood. He seems to have been more popular than his father despite personally carrying out the brutal murder of William Douglas, 8th Earl of Douglas in 1452. He also came to a premature end, however, in an unfortunate accident when a cannon exploded in the siege of the English-held Roxburgh Castle during his campaign to rid Scottish territory of an English army.

James II issued gold coins too, both a demy worth 9s Scots and a lion, worth 10s. He continued to issue billon groats and half- groats – these were now worth just 12d and 6d Scots respectively reflecting the continuing devaluation of the Scottish pound. This exacerbated inflation in Scotland which was already affected by a persistent trade deficit with both England and other countries in Europe.

James III (1460-1488)

James III came to the throne as a child aged just eight, with his mother acting as regent. She was an astute ruler and was able to avoid new con- flicts with England by using the offer of sanctu- ary to the English king Henry VI to re-establish Scottish control over Berwick-upon-Tweed. Un- fortunately she died in 1463 leaving the bishop of St Andrews and other members of the Kenne- dy clan to seize full control. They were however usurped by Robert, Lord Boyd and his clan but that too did not last. James III assumed control, married the 13-years-old Margaret of Denmark in 1469 who brought with her a substantial dowry of 60,000 gold guilders.

This was not paid in full but her father Christian I, king of both Denmark and Norway, had pledged the Orkney and Shetland islands in lieu of the gold and this extended Scottish control of those island groups which now passed permanently to the Scottish crown. This, with the final subjugation of the Lord of the Isles and his Hebridean possessions in 1476, enabled James III to complete the map of modern Scotland. Despite these successes he was not popular and was killed in the Battle of Sauchieburn in 1488 by a rebel army of Scottish nobles that included his 15-year-old son, who emerged from the battle as James IV.

More coinage confusion

In 1460 one Scots pound was valued at just five shillings sterling (i.e. four Scots pound to one English one). James III introduced yet more coin types with yet more unfamiliar names. The first of his new coins was a gold rider, initially worth 23s Scots. It was presumably so-named due to the depiction of James III on a gallop- ing horse, wielding a sword and facing right. Naturally there was also a half-rider and even a quarter-rider.

The rider was followed by the gold unicorn, worth 18s Scots but rising gold prices during the later reign of James V caused its value to increase first to 20 and then 22 shillings. The unicorn is one of the heraldic symbols of Scotland and two of them are to be found crowned and chained as supporters on the royal arms of Scotland. According to the British Museum, the unicorn became the coin favoured by Scottish kings when making gifts to foreigners, as in 1503 when James IV gave 100 unicorns to Lord Dacre, the English ambassador.

Another new coin type – the plack

James III also introduced a billon plack (billon is an alloy of base metal and silver with the silver content usually below 50%). The “plack” is an- other long-vanished name derived from Flemish coins known as “placke” or “plecke”. This one was worth 4d. Confusingly there was also a sil- ver penny worth 3d! A farthing (quarter penny) appeared in 1466 as the first copper coin in Scot- land. Like most other coins it was recognisable by its weight and metal content rather than any denomination actually expressed on it.

Copper coins were known as “black coins” in contrast to silver and billon which were “white” in comparison. The issue of copper coins was profitable for the king, unlike the rare metals gold and silver, coins that often contained more valuable metal than their ostensible face value. Placks and half-placks seem to have been counterfeited fairly regularly and their silver content was sometimes so low that they looked more “black” than “white”.

The first “lifelike” portrait – a silver groat

James III issued a silver groat in 1484 with a much more lifelike portrait of the king on it, the first time an attempt had been made to produce a realistic image of the monarch on a Scottish coin (and somewhat earlier than any equivalent English attempt). At different times during his reign groats of varying sizes and fineness were issued, worth between 6d and 1s 2d, a sad decline from the 4d of the first groats of David II over 100 years earlier. The devaluation certainly made for further confusion in the marketplace.

James III silver groat

James IV (1488-1513)

James IV was a well-regarded king with a good governance record, and a multi-lingual patron of the arts and sciences (he spoke Latin, French, German, Italian, Flemish, and Spanish, as well as English and Scots Gaelic). However, he faced op- position for arranging a truce with Henry VII of England and again with his subsequent marriage in 1503 to Henry’s daughter Margaret Tudor.

When Henry VIII succeeded his father in 1509 relations deteriorated. This culminated in 1513 when James led a Scottish force against England in support of Louis XII of France’s campaign against England. James’s army invaded Northumberland but at the battle of Flodden Field, which turned out to be disastrous for the Scots, his army was routed and he was killed, leaving his one-year-old son to accede to the throne as James V.

The first home-mined gold from Leadhills

James IV continued to issue gold unicorns worth 23s Scots as well as a gold lion or crown worth 13s 4d Scots. He became the first Scot- tish king to benefit from home-mined Scottish gold, albeit having to import foreign miners to improve extraction rates. The gold came from the lead mines of Crawford Muir (Leadhills) in Lanarkshire although the mines only became famous in James V’s reign when sufficient gold was produced to create the Scottish Regalia.

James IV’s silver coins, divided between the initial heavy coinage and the later light coinage, saw the weight of the groat reduced and its value fell from 14d (1s 2d) to 12d (or 1s) Scots. More billon placks were issued, still worth 4d Scots each.

James V (1513-1542)

James V was crowned at the age of 17 months, thus requiring a regent to be appointed to run the country during his minority years. He was able to take full control in 1528 at the age of 16. The first regent was his mother, Margaret Tudor, but after her remarriage in 1514 the role passed to his cousin John Stewart, Duke of Albany, a grandson of James II. Given his an- tecedents he was a credible rival for the throne and had been a fierce opponent of Margaret Tudor, who was widely distrusted given her En- glish connections, to the extent that he mount- ed an army to challenge her position as regent. Margaret ended up in exile in England while Albany was instrumental in renewing and reinforcing the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France. To this end he pledged James V’s hand in marriage to a French royal bride.

At the very end of James V’s reign in 1542 a period of renewed conflict with England erupted, known to Scottish historians as the “rough wooing” (a phrase coined much later by Sir Walter Scott) and elsewhere as the Eight (or Nine) Years War. The conflict arose because of the attempt by Henry VIII to force the Scottish parliament to approve the marriage of the four-year-old Prince Edward (the future king Edward VI) to Mary Queen of Scots. She had ascended to the Scottish throne in 1542 when only six days old but Henry’s efforts were unsuccessful. Additional motives included Henry’s desire protect the English Reformation following his break with Rome and his belief that the Auld Alliance had become a threat to restore Catholicism.

The gold ducat “bonnet piece” makes history

James V continued to issue gold unicorns of 21 carat fineness, valued first at 20 shillings Scots and later at 22s. He may also have struck a so- called “eagle crown” though no examples of the coin have survived. A crown worth 20s did however appear alongside the unicorn. His most memorable gold coin was however the ducat. Some of these coins were minted from Scottish gold from the Crawford Muir mines.

This was a new and uniquely designed gold coin introduced in 1539, famous for two reasons: it was the first Scottish coin to bear its year of issue and it carried a unique portrait of the king wearing a hat rather than his crown. It weighed 88 1/3rd grams and worth 40 shillings Scots and was immediately dubbed the “bonnet piece”. 2/3rd and 1/3rd ducats worth 26s 8d and 13s 4d respectively were also issued.

“The name derives from the Latin and meant literally “the duke’s coin”

The ducat was originally a Venetian coin first issued in 1284 but its use spread across Europe, meeting the need for a unit of account in international trade, displacing in some regions the “florin” of Dutch origin. The name derives from the Latin and meant literally “the duke’s coin”.

The first bawbee also makes history

James V was also the first to issue bawbees. This name has lived on in folk memory even though the coin itself was a humble billon piece, worth 6d Scots (or ½d English sterling) and circulating alongside the billon plack worth 4d.

The origin of the word is disputed. The most widely accepted version is that it was named after Alexander Orrok, the Laird of Sillebawby, who was appointed the Master of the Mint in 1538. Sillebawby was a farm to the north of Burntisland in Fife, named on modern maps as Balbie Farm (and said to be pronounced “bawbee”).

An alternative origin offered by Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1895) is from the French “bas billon” meaning debased copper money. Either way, the bawbee has entered the vernacular as a word meaning a halfpenny, or more generally something of very little value, not necessarily a coin. The bawbee may yet get a new lease of life if it becomes the name of an independent Scotland’s new currency, as advocated by some, possibly with tongue in cheek!

Conclusion

The Scottish economy had developed only slow- ly during the reigns of James I to James V but the pace of change began to accelerate as we move into the mid-16th century. The next article will look at the complex and often beautiful coins of Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1567) and those of her successor James VI (1567-1625) who be- came James I of England in 1603. The Union of the Crowns prompted many changes to the coinage of both Scotland and England.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Spink, Noonans, Stacks-Bow- ers, Davissons Ltd and other firms for the use of images of coins they have handled.

By Jonathan Callaway