Pen Hadow

IT’S NOT ALL WHITE AT THE NORTH POLE

PEN HADOW, BRITISH EXPLORER & CONSERVATIONIST

Alone on the Arctic Ocean, 1,500 kilometres from anyone, I lay in my tent in reflective mood, as the drifting sea ice headed southward from what had been my ultimate destination, 90º North.

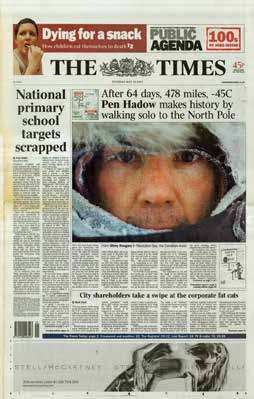

In 1989 I had decided to attempt to become the first person to trek, solo and without being resupplied, across the sea ice from Canada, the harder of the two classic routes (the other being from Russia), to the North Geographic Pole. To succeed on this singular mission had required the sacrifice of many things and an unrelenting focus to address the array of mission-critical subjects, issues and challenges. The process had involved building up 10,000 hours of experience travelling across the sea ice, and attempts in 1994 and 1998, before my eventual success on 19th May 2003.

As I drifted 70km from the Pole over the following nine days, waiting for the weather to improve to enable the pilots to land on my ice floe as originally planned, one aspect of my journey kept interrupting my thoughts. Of the 850 hours I had been on foot, hauling my sledge northwards, I’d spent over 30 of those hours swimming the stretches of open water between the ice-floes, towing my sledge-boat behind. So, it raised the question, How much of the rest of the Arctic Ocean’s perennial sea-ice cover was open water? And what would be the knock-on effects of sea-ice loss for the region, and for those living elsewhere in the northern hemisphere? … And had I just undertaken a journey or a voyage?!

The more common question, asked by so many is Why? Why do explorers commit themselves to such hazardous, demanding and seemingly pointless endeavours? Wally Herbert, leader of the British Trans-Arctic Expedition of 1968-69 – the first surface crossing of the entire Arctic Ocean by its longest axis, from Alaska to Svalbard via the North Pole, and arguably the most talented British polar explorer of all time – gave as good an answer as any, replying to the effect: ‘For those who need to ask the question, there’s little hope of understanding the answer.’ Ouch! Next question, please.

My view on the role of today’s explorer is that it’s never been more important or urgent in human history, if you accept that the natural world, the health of which our own existence depends on, is showing signs of stress and failure in response to our activities. And the explorer’s role? The more we can discover and share with others how the natural world’s resources, processes and ecosystems work, the better positioned the voting general public, and consequently our governments, will be to develop the sustainable relationship with the natural world that’s essential to our survival.

Herbert’s privately-organised 6,000 km, 15-month traverse of the Arctic Ocean with three sledging partners and their dog-teams, was completed only weeks ahead of Man’s first landing on the Moon, which says something about both the challenges to be faced on the ‘top of the world’ and how little was known about this minimally explored region. At the time, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson described it as “a feat of endurance and courage which ranks with any in polar history”. Herbert was later deservedly awarded the Polar Medal for his exploration work in both the Arctic Ocean and Antarctic regions, and was knighted in 2000.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the Polar Medal has a history of its own, firmly anchored in British polar exploration. It had formerly been known as the Arctic Medal, an octagonal-shaped medal first instituted in 1857 and was awarded only twice by the British Admiralty in the 19th century. First, to ‘all ranks’ engaged in Arctic expeditions between 1818-1855, including some to discover the fate of Sir John Franklin and his crews aboard HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (1845-47), all of whom died in their quest for a route through the Northwest Passage.

The second wave of awards was to all ranks aboard the British Northwest Passage Expedition’s Pandora (1875) led by Allen Young, together with the officers and crew aboard the British Arctic Expedition’s HMS Discovery and HMS Alert, commanded by George Nares (1875-76).

Until 1968, the Polar Medal was presented to anyone who participated in a polar expedition endorsed by the governments of any Commonwealth country. Since then the rules governing its presentation have been revised, with greater emphasis placed on personal achievement. A total of 880 silver and 245 bronze medals have been issued for Antarctic expeditions; and another 73 silver medals for Arctic expeditions. For those conferred the award a second or third time for subsequent expeditions, ‘clasps’ are received instead, with Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce sharing the record of four clasps.

the medical researcher and sledging partner to Robert Swan and Sir Ranulph Fiennes; and the wildlife cameraman and photographer, Doug Allan.

Most recently it has been used widely to reward the personnel of United Kingdom and Commonwealth government research programmes, whether by land, sea or air. Thus recipients have largely been the government funded scientists and field guides of the British Antarctic Survey who ‘over prolonged periods of time and in harsh conditions have advanced knowledge of the polar regions’.

My fascination for things polar was the product of a powerful cocktail of childhood influences. As a child I’d been looked after by an elderly Enid Wigley, whose first charge 50 years earlier had been Peter Scott, the only child of Captain Scott himself. In Scott’s last letter to his wife, written as he lay dying in his tent with no hope of surviving, he hoped Kathleen would “Get the boy interested in the natural world, there are some schools that see this as more interesting than competitive sport.” In later life, Peter went on to set up the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust based at Slimbridge, and the world’s largest membership organisation for the protection of the natural world, the Worldwide Fund for Nature (aka WWF). He also became television’s pioneering presenter of the natural world with his BBC programme, Look. After 26 years, he eventually handed on the baton … to the young David Attenborough!

Much of what Enid absorbed while living with the Scott family she passed on to me, notably the personalities and stories of Antarctic exploration who collectively we referred to as the ‘Antarctic Boys’ – Ernest Shackleton, Douglas Mawson and Adrien de Gerlache. I also share the benefits with Peter of a childhood regime involving being urged outdoors as much as possible with the minimum of clothing in the autumns, winters and springs ‘to inure us to the cold’. Peter endured this for 5 years in southern England. I lasted only for 3 years in Perthshire because when frostnip was spotted on my face, my mother thankfully pulled the plug.

My polar life began in earnest in 1989 with a baptism-of-fire unsupported 70-day sledge-hauling journey across the sea ice between the islands of Svalbard’s archipelago to photograph polar bears ‘in the wild’. I never looked back …

For me, the cumulative effect of having had to swim repeatedly from ice floe to ice floe on my way to the North Pole led to a Damascene moment, as I lay drifting in that tent. I felt an overwhelming sense of responsibility to study, and share with the wider world, the scale, rate and likely impacts of this sea-ice loss due to global warming. I soon began work developing what became the £6.5 million international marine research and public engagement programme, Catlin Arctic Survey (2008-2012) which investigated some of the causes and consequences of sea-ice loss. The Surveys generated £90 million worth of media coverage worldwide on behalf of the otherwise unknown, unseen and unheard wildlife of the Arctic Ocean. The story was spreading and the science was getting done. But while the scientific research was imperative, it had no obvious end – and events were now fast-overtaking the Arctic Ocean if anything was to be done to protect its ecosystem.

In 2017 I sought to demonstrate how accessible the international waters of the northernmost Arctic Ocean had become to commercially-operated vessels due to the rapid melting of the sea ice in the summers.

Our two 50-foot sailing vessels became the first ever to enter these waters without icebreakers, eventually reaching as far as 80º 10’ North.

While we also undertook scientific research to investigate the nature and state of the region’s unique marine ecosystem, the voyage led to two invaluable insights. That the Arctic Ocean’s sea-ice cover, commonly perceived as a lifeless surface feature, urgently needs to be understood for what it is – a floating ice-reef ecosystem upon which a complex web of plants and animals depend for their survival.

Secondly, that the observed loss of sea-ice is therefore not only a geophysical phenomenon with major consequences for global ocean and atmospheric circulation, but is also the loss of a unique floating ice-reef habitat, with major consequences for its dependent wildlife. Imminent disruptive, damaging and destructive commercial activities urgently needed to be controlled to minimise any additional direct human pressures on this super-vulnerable ecosystem.

Will a time come when there is no sea ice in the summers? Yes, probably by 2050 at the latest. Is it possible the sea water and air temperatures will be so warm that no sea ice will return in the winters. Well, yes. Possibly as soon as 2100. Hmm. And what wildlife are we thinking of, exactly? The world’s second largest animal, the 100,000kg Bowhead Whale, and the world’s only seabed-feeding whale, the Gray Whale; seal species including Harbour, Ribbon, Bearded, Spotted, Hooded and Ringed; all three subspecies of Walrus; the world’s largest dolphin, Orca; the spiral-toothed Narwhal (the source of the mythical unicorn); the most sophisticated communicator of all whales, the Beluga Whale; and one of the world’s ultimate apex predators, the Polar Bear. And these are just the mammals! How does a marine protected area ensure all the current species, depending on the sea ice for all or part of their life cycle, are saved? It doesn’t. It can’t. Protecting the area from direct human activities will not save the sea-ice habitat – only by reducing our greenhouse gas emissions can sea-ice formation be restored.

So what is the point in creating a protected area? Well, the alarming likelihood is this region will become the refuge of last resort for hosts of marine animal and plant species currently living far away to the south as ocean temperatures continue to rise. With some species already tracking northwards to these cooler waters, the North Pole’s international waters are now becoming an ultima refugium for wildlife, an Arctic Ark, if you like, offering a similar service to that of Noah’s Ark). This is why the international community should prevent all additional and avoidable disruptive, damaging and destructive direct human activities from even starting in the Central Arctic Ocean – to minimise the stressors on wildlife in its desperate efforts to survive. These waters are likely to be the last hope for a myriad of species and, likely as not, the human race, which depends on the planet’s biodiversity and the health of its oceans for its oxygen, fresh water and processing of waste.

As seen from space, Earth looks to be a blue planet, with Antarctica’s ice sheet and the Arctic Ocean’s sea-ice cover providing the white colouring around our Poles.

But human induced climate change is rapidly melting the North Pole’s sea ice, turning the region from white to blue. Together we are literally changing the face of our planet as seen from outer space. And so our 90North ocean conservation advocacy unit was founded to provide the leadership to create the world’s largest marine protected area. At the highest level, it will offer a unifying and universal symbol of the global community’s commitment to creating a sustainable future for our biosphere.

For further information, or to support 90North’s work, please text 07970 619 161 or visit www.90northunit.org; and for Pen Hadow’s speaking services visit www.penhadow.com