Olivia Marshall

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SHAH JAHAN DIAMOND

Readers may recall mention of the ‘Shah Jahan’ Diamond during our interview with Anthony Spink in issue 34 of the Insider last year. The diamond in question, which appeared in a 1985 Christie’s sale in Geneva, is a pink-toned 56-carat table cut of a ‘spectacular’ nature. The head of the Indian family who brought the diamond to auction, who was by then very elderly, had once been a senior advisor to the Aga Khan, a spiritual leader of the Ismaili branch of Shiite Islam. This man had inherited the magnificent stone from his own father, and it is assumed the stone was passed down through many generations of the family, appearing to have departed India with the Persian invasion in the mid-eighteenth century; when the diamond failed to sell at the auction, it was privately sold to a European family. It is clear from many years of research into the stone that it is a strikingly unique specimen which covers an immense history – but what makes the Shah Jahan diamond so special?

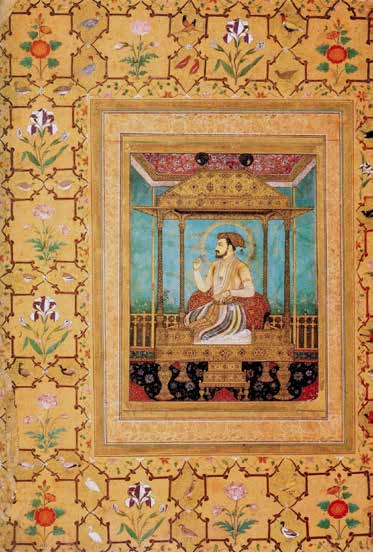

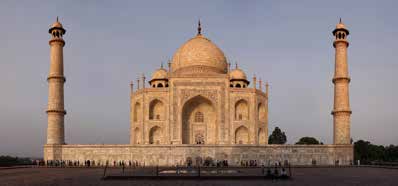

Shahab-ud-din Muhammad Khurram, who went by the shortened name of Shah Jahan, was the fifth Mughal emperor, notably known for his contribution to Mughal architecture – including the commission of the spectacular Taj Mahal, which was commissioned in 1632 to house the tomb of his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal (and also the tomb of Shah Jahan himself). The diamond is attributed to the emperor as far back as 1860, after French jeweller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier claimed in 1642 that it formed part of the Great Table diamond which studded the Shah’s throne during his reign (from 1628 to 1658).

Although people long accepted this story, it has since been proven otherwise. In the late 1960s leading Canadian gemmologists discovered that the infamous Great Table diamond had in fact been cut into two gems, the Darya-I Nur and the Nur ul Ain, proving that the pink diamond in question could not have formed part of the Great Table and dispelling the long-believed myth.

However, the diamond was found to have an equally interesting history of its own – and one not altogether different from that which was once assumed. After being examined by specialists at the Institute of Geological Sciences, the diamond was linked to a painting which is displayed in the Freer Gallery in Washington, which depicts Jahangir Shah (fourth Mughal emperor and father of Shah Jahan) wearing a bracelet which contained a similar stone, of a table cut. Furthermore, a corresponding miniature was found in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum which illustrates Shah Jahan holding a turban ornament called a sarpech, made of gold and bejewelled with a cushion shaped emerald and, below it, a familiar octagonal diamond. Despite the naturally ‘miniature’ dimensions of the piece, when examined closely it has been found to almost perfectly resemble the diamond under discussion – in fact, the resemblance is uncanny. Could this be our stone?

This is no ordinary diamond, and could not easily be mistaken with another. Jobbins and Harding, who examined it at the Institute of Geological Sciences, wrote in The Journal of

A Shah Jahan gold Mohur, sold by Spink

Gemmology in 1984 that it is of a distinctly pink colour, which may be graded as ‘fancy light pink’, despite the conditions under which it was examined not being ideal. An excerpt from the journal, entitled ‘A Brief Description of a Spectacular 56.71 carats Tabular Diamond’, gives the following analysis:

‘The upper surface is step-cut, and the very large table facet (approx. 27.5 x 19mm) extraordinarily smooth and well-polished with an adamantine lustre. However, it is not plane, but slightly curved as shown by the slightly distorted reflections of window frames … the cutting of the rear facets especially may appear crude, but when the stone is viewed in subdued lighting it displays an extraordinary ability to pick up any available light and reflect it brilliantly.’

It was also noted that the corners next to the drill holes appear to have been ground away, and that there was evidence of earlier drill holes due to marks along the edge of the diamond, suggesting that these attempts had failed, possibly due to fracturing. So the stone may have weighed more before the holes were drilled – for context, at the time of the 1985 Christie’s sale in Geneva, the unmounted table cut weighed 56.71 (metric) carats. These drill holes may have been added to allow a piece of wire or cord to be passed through, so that the jewel could be worn as a pendant. It is also possible that the drill holes originally allowed the diamond to be sewn into a turban or piece of clothing – what a statement that would make in the local pub!

It was towards the end of the 1990s that the then owners of the Shah Jahan diamond entrusted it to Spink to find a suitable buyer. Spink explored possible purchasers for this rare and extraordinary diamond carefully and discreetly, and arranged a private transaction. Shortly after that, the diamond appeared in the exhibition “Treasury of the World” at the British Museum, which exhibited the Al-Sabbah collection of jewelled arts of India of the Kuwait National Museum. The Shah Jahan diamond had therefore found a home worthy of it, in arguably the most important collection of Indian Jewellery in the World, thanks to Spink.

This fascinating background to one of the world’s great gemstones is yet another part of Spink’s rich archival history, and one which may still have further secrets to be uncovered.