“If I do nothing else with my life I will make it solo, with no re-supplies, to the North Pole.” These are the last words my father heard as he died in my arms. The words had just welled up unexpectedly from a place deep inside, but my father and I both knew this is was the sort of thing he had been working towards. I needed him to know he had successfully handed me the baton, and that I was not going to stop until it was done, whatever the cost. If ever there was an unbreakable commitment, a vow even, it seemed to me that this was one.

My father, Nigel Philip Ian Hadow, had been idiosyncratic in the way he had approached parenthood, essentially driven by the idea, I have since thought, of preparing me for the ambitious future that had somehow escaped him, despite his myriad gifts. Let me give you an idea of what I mean. And I should preface what follows by saying he was the kindest, funniest and most supportive father a boy could have hoped for. My life course received a heavy nudge early on in the proceedings when I found myself in the care of the same person who five decades previously had been governess to Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s only child, Peter.

One of the letters discovered alongside Scott in the tent in which he and his colleagues had died on their return from the South Geographic Pole was to his wife, Kathleen. In it he urged her to “Get the boy interested in the natural world, there are some schools that see this as more interesting than competitive sport.” He also urged that he be “kept in the fresh air”. These dying requests led Kathleen to take on the soft-spoken Welsh teenager, Enid Wigley, to assist in providing a quasi-Spartan regime for Peter over the following five years. By my father’s account, it had led to some marked physiological, and most likely psychological, effects.

Some years later my grandmother, Sylvia, hired Enid to look after my father when he was a youngster, and he became familiar with the stories emanating from Enid’s time with the Scott household. Peter went on to become an Olympic sailor, a talented wildfowl artist, an innovator of camouflage paint designs for British warships, the founder of the Wildfowl & Wetland Trust and later the world’s largest-membership environmental organisation, the WWF (also designing its giant panda logo), and he was the first television presenter of natural history (BBC’s Look), handing over to David Attenborough. Sir Peter was arguably the first global environmental figure. Sir David is perhaps the second.

So it was that in her seventies, Enid’s services were secured by my father to “give me the Scott treatment”. Unfortunately for me, we lived on the edge of the Ochil Hills in Glendevon near Geneagles (Perthshire, Scotland). Now the winters up there were a wee bit fresher than those young Peter experienced in southern England. I mention this because part of the regime involved building tolerance to the cold, so throughout the autumns, winters and springs I’d find myself outdoors on our farm with less and less clothing for longer and longer periods. It was only when my mother spotted frost-nip on my face that she was able to bring an end to the cold-proofing process … three years later.

And so it came to pass, in 2003, that I was to make my third solo attempt, without resupply by aircraft, from Canada, the harder of the two classic routes, to the North Geographic Pole. The route from Russia’s northernmost point on Komsomolets Island in the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago involves a longer distance, but with the region’s sea-ice drifting pole-wards, the actual distance is in effect similar to that from Canada. But as this sea ice is drifting away from the coast, the ice floes experience negligible compressional forces, so hardly any pressure ridges are formed. On a guided expedition I led from the Russian coast, I only had to remove my skis five times over 60 days. From the Canadian coast, taking one’s skis off five times an hour, 12 hours a day for 30 days is the norm, so large and frequent are the pressure ridges (4,500 of them, to be precise, in 2003). Simply put, they make for utterly exhausting work, worryingly slow progress north, and an unremitting test of mental resilience to the nth degree. In addition, by approaching the Pole from the Canadian side, the closer you are to the Pole, the faster the sea ice is flowing against you, thereby acting like an airport travelator in the wrong direction.

I had failed in 1994, and I had failed again in 1998; although I now see these not as failures, nor even as temporary setbacks, but the essential experiences I needed to find the keys to unlock the doors to eventual success. Over the last 100 years, most expeditions attempting to reach the North Geographic Pole, from both the Russian and Canadian coasts, have failed by the criteria they originally set themselves. For example, if three people set off with the intention of three resupplies by air (thereby making their sledge loads smaller and lighter to haul), two might reach the Pole and claim success, though the third person may have been airlifted out, thanks to an additional fourth aircraft intervention, with freezing cold injuries (FCIs) – or they simply wanted ‘out’ from all the privations, suffering, and an increasing conviction that the Pole was unattainable.

On my first attempt in 1994, my approach had been to take two of everything I felt essential. The trouble was, everything was mission-critical. So my all-up sledge weight had been 175 kilograms – almost impossible to haul across even level ice floes, but not quite. Any pressure ridges involved shuttling smaller loads up and over before the sledge could be hauled up the 45º slopes of chaotically jumbled ice blocks. The following year I set up the first guiding service to the North Pole from Canada in a deliberate strategy to build up the body of experience I realised I needed. After all, the Arctic Ocean and its sea-ice surface posed a number of entirely unique technical challenges to the sea-ice traveller. So while a supremely positive and resilient mindset would be essential, technical skills and operational experience were going to be equally essential. As Malcolm Gladwell proposed in Outliers, for those in specialist areas who train in the order of 10,000 hours, world-class performance tends to follow. Since first conceiving of my solo without resupply by the harder route in 1989, it happened that by 2003, I had spent close to 10,000 hours travelling on the Arctic Ocean. I had secured that critical body of experience that simply cannot be obtained from books, films, lectures, and personal briefings from generous-minded fellow explorers alone.

To reach my start point on the edge of the Arctic Ocean from London involved four scheduled flights followed by two charter flights, each heading ever further north. The final of these was to the uninhabited Ward Hunt Island (83º 05’ North), which lies off northern Ellesmere Island, it’s Canada’s northernmost coastline. To reach the North Geographic Pole from here I’d be setting off from one of the world’s northernmost ‘beaches’ and making my way across 770km of constantly-drifting, partially-frozen ocean surface to 90º North – the point marking the axis of our planet’s rotation in the northern hemisphere. I spent two weeks undertaking my final preparations in the remote Nunavut settlement of Resolute Bay (74º 30’ North) on the northern shore of the Northwest Passage.

Most of my focus was on reducing the weight of my sledge to its eventual 117 kilograms, plus a 15kg backpack. Long ago I’d discovered that cutting one’s toothbrush in half is a false economy. If you’ve ever tried cleaning your teeth with half a brush, you’ll know what I mean – you end up not cleaning your teeth. Over 75 days that can cause serious dental issues which are then compounded by the extreme oral environment, such as the thermal cycling my teeth had to endure, with one moment -40ºC air being drawn over them, and the next, a cup of +80ºC tea washing over them, followed immediately by another inhalation of -40ºC air. Add to this the differential rates of contraction in response to temperature for teeth and for fillings, and throw in some iron-hard nuts or chocolate bits, and you can see the stresses on just this part of your anatomy. Lose a filling, or crack a tooth, and 75 days can feel just a little longer – I had both, despite having all my fillings replaced to mitigate against this risk. And these were just two of the 164 risks I had listed, each with an assessment of the likelihood and scale of impact, the mitigations I could take to minimize the risk, and the actions necessary if they occurred.

When later commissioned to write my account of the expedition by Penguin Books, I wrote 32,000 words in the first eight days. The book required 120,000. All good, until I showed the 32,000 words to my editor. “Terrific writing, Pen” he said, “but so far you’ve only shared with us your three days in the hut on Ward Hunt Island before you set off!” All I can remember now of those tense three days alone in the world’s most remote abode, aside from the asthmatic breathing sound the tiny wooden hut made as the wind-gusts struck, and the dread of a polar bear locking onto the smell of my cooking and ripping off the scantily secured door, was the sheer enormity of the challenge I had set myself for the next 75 days: the monastic-like privations ahead; the resilience necessary to get through all the dark and desperate moments; the relentless obsessive drive needed to wake up on schedule, prepare for the day ahead in extreme cold, and then commit to taking down my single-layer shelter and setting off each day; and somehow to keep going, just keep going …

It is appropriate to acknowledge at this point that as with any pioneering feat at the bleeding edge of one’s specialism, such a solo attempt was built upon the talents and commitment of my predecessors. Britain’s Sir Ranulph Fiennes introduced the concept of unsupported expeditions to the North Pole (ie no resupplies, no personnel insertions/extractions, and the use of only human-power – so no snowmobiles, dogs etc), though four of his five attempts were with a sledging partner. Japan’s Naomi Uemura had been the first to ‘solo’ the North Pole in 1978, employing seven resupplies and a dog-team from Ward Hunt. France’s Dr Jean-Louis Etienne also made it ‘solo’ with only five resupplies and no dogs in 1986 from Ward Hunt. Meanwhile, Norway’s Borge Ousland had made it truly solo (i.e. without resupply by aircraft) from Severnaya Zemlya on Russia’s northernmost coast in 1994.

Between 1990 and 2002, there had been approximately 15 solo unsupported attempts from Canada (including two by myself) by well-known adventurers, professional polar guides and special forces personnel, most pulling out in the earlier stages of their attempt. But by 2001 Japan’s Hyoichi Kono had made it ‘solo’ with just one resupply to the Pole. The clock was ticking if I was to be the one to push through this final performance barrier, though many in the polar community had come to see the challenge as likely impossible. World-leading high-altitude mountaineer Reinhold Messner, who had been the first person to solo Mt Everest and later made an unsupported attempted to the North Pole from Russia (partnered with his brother), quickly withdrew when he realised that sea-ice travel presented challenges quite unlike those of mountains and declared the first solo unsupported North Pole journey comparable to making the first solo ascent without oxygen of Mt Everest by the harder of the classic routes.

On 17th March 2003, after waiting three days for the winds to drop and the -40ºC air temperature to freeze the open water areas, I struck out northwards towards ignominy, success or death. There is no way I can convey what it’s really like. It’s a complex interaction of emotions, situations and decisions that produces an intensely internal personal experience. So while the outside observer is left with the basic constituents of ocean surface conditions, the weather conditions, the daily progress north, one-line (or even one word) daily operational summaries and the (very real) possibility of disaster at any moment, it’s an entirely different thing out on the ice.

For the first few days I’d looked to do at least six sledging sessions of 75 minutes, with a 10 minute break between each session for a cup of tea from one of my two thermoses and a handful of mixed nuts, chocolate drops, and salami slices from my ‘sledger’s nose-bag’, then build this up to at least nine sessions a day as soon as possible. I knew I should plan to cover only 110km in the first 20 days, leaving 660km to cover with the remaining 45 days of supplies. This requires real confidence in the viability of the plan.

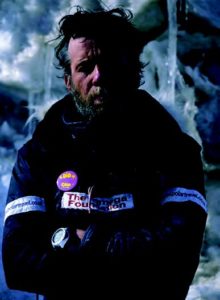

Of the cumulative 850 hours I spent hauling my sledge, 30-40 hours were spent fully dressed inside my immersion suit as I swam the open water sections between the ice floes, towing my sledge behind. The first 35 days saw ambient air temperatures ranging from -28ºC to -46ºC, but by the final 10 days it was more like -3ºC to -15ºC. Any temperatures warmer than -20ºC were ‘positively touristic’ if not uncomfortably sweat-inducing given my work rate across the sea ice. However, over the years I’d also realised that if the wind took effective temperatures to below -70ºC, it was much more likely I’d make a mistake, and I’d also be dramatically less able to recover the situation due to being on the cusp of what would rapidly become terminal hypothermia.

Entirely alone, with any assistance potentially 10 days away subject to the weather, in a complex and hazardous environment, while constantly pushing myself far beyond my own known limits on several fronts to push back a little further what was known to be humanly possible, is a rare and privileged space to occupy. No mistakes could be made at any scale at any time for 75 days. For those first few days, I just wanted to survive and quietly find my routine. My mind lived on a knife-edge for the next month, with the relentless pressures – big and small – exerted by the oppressive cold on my human frame, processes and systems, often frightening to overcome. They took their toll.

By Day 46 around 87º 30” North, I was heading for mental burnout. I know because I made my first mistake and it was a potentially life-ending one. I misjudged the ice thickness and broke through without my immersion suit. Only a well-rehearsed mental drill saved me. On Day 54, having just passed 88º North, while trying to find a way off one ice floe onto another, I came across the ski and sledge tracks of a previous year’s expedition. Absolutely extraordinary! Until it dawned on me that not only was that basically impossible for very many reasons … but that they were my own tracks. So intent on finding a way off the floe, I had not realised I had moved through 180º while working my way around the edge of the floe! By Day 62, my brain was struggling to cope with the cumulative stresses of the journey, despite being so tantalizingly close to my final destination. I couldn’t even add 8+5+3 in my head as I skied along. I needed to reach the Pole as soon as possible, to finish the job – but then again, not push on and bring about the very misjudgements I feared could yet finish me. Always a balance. Keep calm. Don’t blow it now.

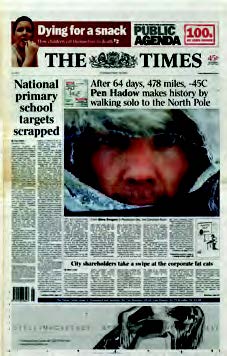

Over the final three days I was sledging round the clock for three days and nights to minimize the effect of the southward drifting sea ice on my progress over the ground (ie seabed) to the Pole. If I stopped for too long, I’d never reach the Pole but be carried backwards faster than I could make up for. But my time had finally come to succeed. At 09.54 GMT on 19th May, 64 days after setting off, I stood at 90º North. And how did I feel? I felt utter, utter relief that I had finally done it. My mission had taken 15 years since its inception in 1989. Three attempts. And one vow. All for this one precious private moment. I felt on top of the world!

And where has all this led, you may ask? My 25 years travelling on the sea ice and those repeated swims in the Arctic Ocean between the floes opened my eyes to the North Pole region’s rapidly diminishing floating ice-reef ecosystem and the wildlife that depends upon this habitat. My rest-of-life mission, delivered through our 90North Unit ocean conservation charity, is to catalyse the process to create the world’s largest wildlife reserve – the North Pole Marine Reserve – for the entire area of international waters in the Central Arctic Ocean through an international treaty.

A selection of Pen Hadow’s solo North Pole collection of items will be offered for sale in our Orders, Decorations and Medals auction, to be held at Spink London on 8th and 9th December 2020. For further information please contact Marcus Budgen, [email protected].