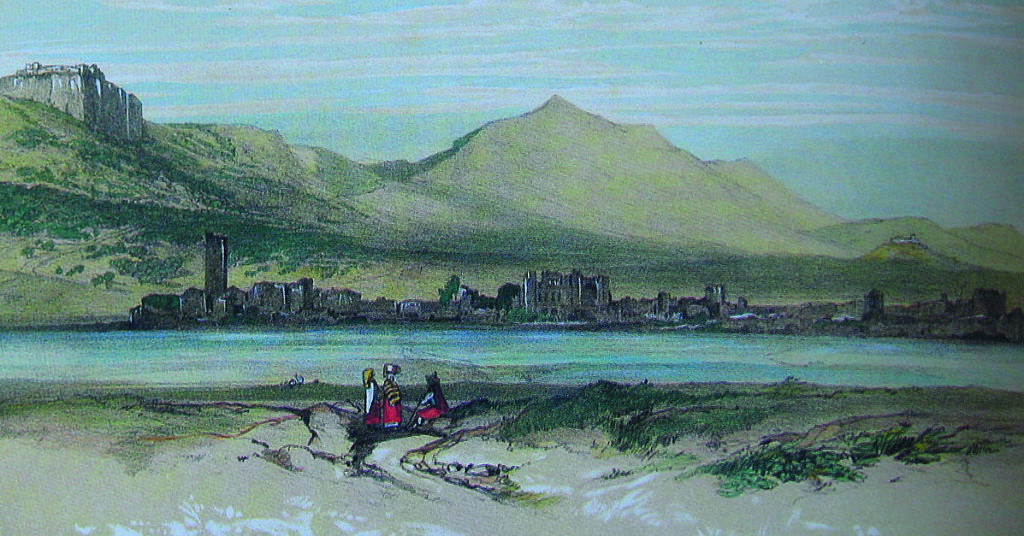

The romantic garden of Ninfa, just 65 miles south of Rome, was created by the Caetani family almost one hundred years ago, and lies among the eloquent ruins of a small but affluent medieval town, which in turn grew out of Roman and papal settlements, and passed to the Caetani in the early fourteenth century. Their family history marks every stretch of the Tyrrhenian coastland – from Pisa, Rome, Cisterna, Ninfa, and Sermoneta and on down to Fondi, Gaeta and Naples. In the family history Domus Caietana, the ninth-century Anatolio, Lord of Gaeta, is the first of the Caetani to gain regional prominence. By the thirteenth century, the Caetani were a powerful Latium dynasty, with two family popes, several cardinals and considerable military prowess. They held sway over the entire Pontine region to the south of Rome.

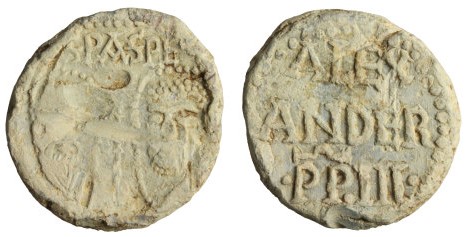

The history of Ninfa is therefore almost a history in coins; whether in display cabinets or lying deep in the pockets of the ordinary man coins have spoken in the course of history of the power and authority of sovereigns, emperors, popes, anti-popes and even a minor cardinal here or there. Most civilisations have been affected by the actions of those entitled to be ‘minted’, so to speak, or by the volatility of their coinage in terms of economic value. The medieval relationship between empire and papacy in the minting of coins, indeed in the exercise of power, was often fraught, and few of Italy’s dynastic families can have been more affected by that relationship than the Caetani, who were never far removed from the actions of those whose heads appeared on the portrait coins of their times.

Pliny the Younger, writing in the first century, records the existence of a small Roman temple dedicated to the water nymphs, close to an abundant spring at the foot of the Lepini hills. By the end of the Roman Empire, with the Appian Way in disrepair and repeatedly flooded by the famous Pontine marshes, the stretch between Cisterna and Monte Circeo was abandoned and ‘re-sited’ inland, a few meters above sea level, at the foot of the Monti Lepini and passing close to those alluring spring waters. A settlement inevitably grew up there, travellers rested, watered their horses, and paid a toll. The spring waters were dammed and harnessed for milling and other purposes. Ninfa ceased to be an imperial possession in the eighth century, when the Holy Roman Emperor Constantine V (718–775) made a gift of it to Pope Zacharias (741-752), one of the earliest popes in whose honour a coin was minted.

The little town grew in size and in commercial importance. Mirroring Rome, seven churches were built, the most imposing of which was Santa Maria Maggiore, whose ruins date from the tenth century and are imposing to this day. Holy Roman emperors were often at odds with the papacy, the Holy See being twice occupied by the Caetani. In 1118, Giovanni da Gaeta succeeded Paschal II to become Pope Gelasius II. Persecuted by Emperor Henry V (1086–1125), whom he fruitlessly excommunicated, Gelasius lasted just one year as pope, dying in exile in 1119. In 1159, the elected pope, Alexander III (c. 1100–1181), escaping from the Roman supporters of Emperor Frederick I’s anti-pope Victor IV, took refuge in Ninfa where he was formally consecrated on 20 September 1159 in Santa Maria Maggiore. Frederick, or Barbarossa as he was known (1122–1190), took his revenge and wrecked the town, but it rose up again, adding further to its fortifications. Alexander died in 1181.

Caetani history gives way now to Benedetto Gaetani (1235-1303), whose family had settled in Anagni, between Gaeta and Rome. In 1294, succeeding the hermitic St. Celestine V, he was elected pope and took the now notorious name of Boniface VIII. A competent canon lawyer and patron of the arts, he founded the Rome University of La Sapienza and renewed the Vatican Library. His pontificate, however, was mired by constant disputes with Philip IV of France (1269–1314).

His provocative Bull Unam Sanctam (1302), an extreme affirmation of papal supremacy, led to the humiliating circumstances of his arrest in Anagni in September 1303, and the pillaging of his palace by Henry’s forces. Outraged and shaken, the elderly Boniface died a month later. Always controversial, he was perhaps the last of the medieval emperor-popes.

In his lifetime, the opportunist Boniface heightened the power of his family through territorial expansion. Notable was his personal acquisition of burgeoning Ninfa, of which he then made a gift to his nephew Pietro Caetani in 1301. Pietro’s iconic 40-metre tower, which still stands tall over the garden today, and Ninfa’s double girdle of fortified walls, were not enough to save the town from being ruthlessly sacked in 1381 against a background of schism, papal wars and inter-family territorial disputes.

For five fallow centuries, during which Ninfa’s ghostly ruins almost vanished in a growing forest of vines and thickets, an incubator of the dreaded malaria, the dynastic feuds carried on. A simmering rivalry between the Caetani and Colonna families was followed in 1499 by a drama of potentially crippling consequences – the confiscation of all Caetani properties by the Borgia pope, Alexander VI.

Happily these were restored by Pope Julius II in 1504, soon after his accession. In spite of this confrontational climate, the Caetanis increased their influence, particularly in the Pontine region. The impregnable Castle of Sermoneta is today’s enduring monument to the family’s medieval power.

This lush Pontine heartland of the Caetanis, essentially the Sermoneta estates, peaked with a boundary of over 100 miles. From ancient times, though, there remained one colossal challenge, namely the marshes. Successive attempts were made to restore what Pliny described as the ‘blossoming landscape’ that existed at the time of the Volsci tribal settlers in 500 BC. For centuries, Roman emperors, including Trajan, vainly sought the means; then, with Ninfa a papal possession, popes tried their hand, including Boniface VIII and Sixtus V who died of malaria in 1590 after a visit to the marshes. The seventeenth and eighteenth century dukes of Sermoneta were likewise unsuccessful. Only in the twentieth century was the challenge met, and the genius behind it was Gelasio Caetani (1877-1934). Cultivated and resourceful like so many of his family, Gelasio was a trained engineer who worked in his early career with several American mining companies. He used his knowledge of explosives to devastating effect during the war with Austria, between 1915 and 1917. The war over, he now turned those same skills to devising a plan for the marshes. The reclamation work, which included the use of explosives to create a series of drainage canals, was carried out in collaboration with armies of labour, some immigrant, provided by the Italian State. It was completed in the early 1930s.

Palaces and strongholds associated with the Caetani remain – in Rome, Cisterna, Sermoneta and Fondi. Looking back, though, the Caetani story is not just one of power or survival. The twentieth century alone produced a generation of Caetani steeped in the arts, in scholarship and in music. One calls to mind two of Gelasio’s brothers – Leone (1869–1935), the renowned Islamist scholar, and Roffredo (1871–1961), a gifted composer, and last duke. Gelasio is remembered for many things, among them his extraordinary vision in clearing the ruined medieval site of Ninfa and, with his English mother, laying out the unique garden we see today and planting the first cypresses and roses. Within three decades Ninfa was to capture the imagination of musicians, artists, poets and gardeners from all over the world.

Opinions have always differed as to whether the appeal of Ninfa, its enchantment or incanto, relies more on its natural and environmental advantages, in particular that life-enhancing supply of water, or on its spectacular ruins – a fine double girdle of fortified walls, a castle, a town hall (now a villa), churches, and an array of private homes to the 2,500 inhabitants of the town at its medieval peak. At every turn a new and absorbing vista: exquisite plantings in the Caetani tradition, lavender-lined walkways, roses climbing into the heights of 100-year-old cypresses, ruined walls and towers no longer crushed and obscured by vegetation but adorned by complementary planting of the highest order, bursts of spring blossom and brilliant contrasts between light and shade on the best of many sunny days. There is no easy answer, but one simply cannot imagine Ninfa without these foundational elements.

Duke Roffredo’s daughter Lelia, last of the Caetani heirs, died without issue in 1977, having set up a foundation to own and manage all her country estates, including Ninfa. Designated a Natural Monument by the Italian State in 2000, Ninfa’s greatly reduced boundaries, once threatened by hostile armies, contend these days with the press of tourism – some 65,000 visitors a year from all over the world. The incanto, however, remains. Ninfa is open to the public for a limited number of days between April and October.

For more information, and to arrange special group visits, please go to: www.fondazionecaetani.org

Esme Howard is a nephew of Donna Lelia Caetani, a former member of the general council of the Roffredo Caetani Foundation that owns Ninfa, and founder and coordinator of the International Friends of Ninfa (UK).

Bibliography

Charles Quest-Ritson Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World (Published by Frances Lincoln, 2009)

Lauraine Dennett: An American Princess: The Remarkable Life of Marguerite Chapin Caetani

(Published by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017)