Dr Richard Kelleher, Senior Curator of Medieval and Modern Money at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

DEFACED! MONEY, CONFLICT, PROTEST

A NEW EXHIBITION AT THE FITZWILLIAM MUSEUM, CAMBRIDGE,

11TH OCTOBER 2022 – 8TH JANUARY 2023

Defaced! Money, Conflict, Protest is the first major exhibition to display money which has been re-used as a canvas for political and social rebellion. Over the past 250 years Defaced! presents a history of protest through currencies that have been mutilated as cries of anger, injustice, mockery or despair. From the biting humour of a rare intact sheet of Banksy’s ‘Di-Faced Tenners’ to a unique coin commemorating the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, the exhibition showcases a new collection of defaced coins and banknotes recently acquired for the Fitzwilliam thanks to support of the Art Fund’s New Collecting Award, complemented by important loans from museums and private collections. The acts of defacement on show reveal the hidden struggles behind some of the major events of the past 250 years, as diverse as the French and American Revolutions, the suffragette movement, the Siege of Mafeking, the Spanish Civil War, the Nazi concentration camp system and occupation, the deadly sectarian Troubles in Northern Ireland, and the Black Lives Matter protests. Money is both a medium and a metaphor and its physical representations – coins or banknotes – contain layers of meaning that activists and artists have manipulated, challenged, dismantled and subverted for more than 200 years.

Changing values

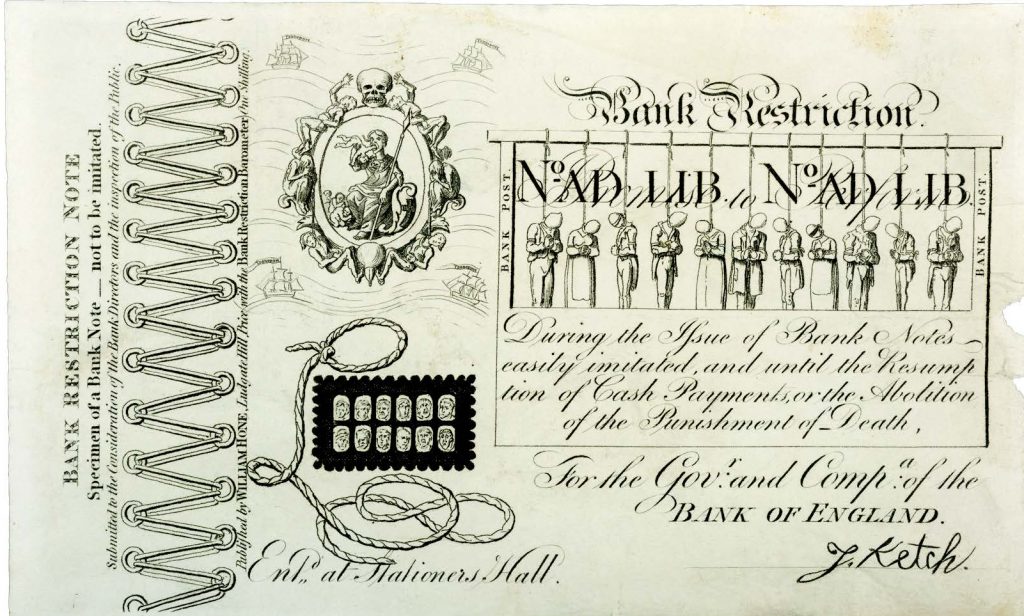

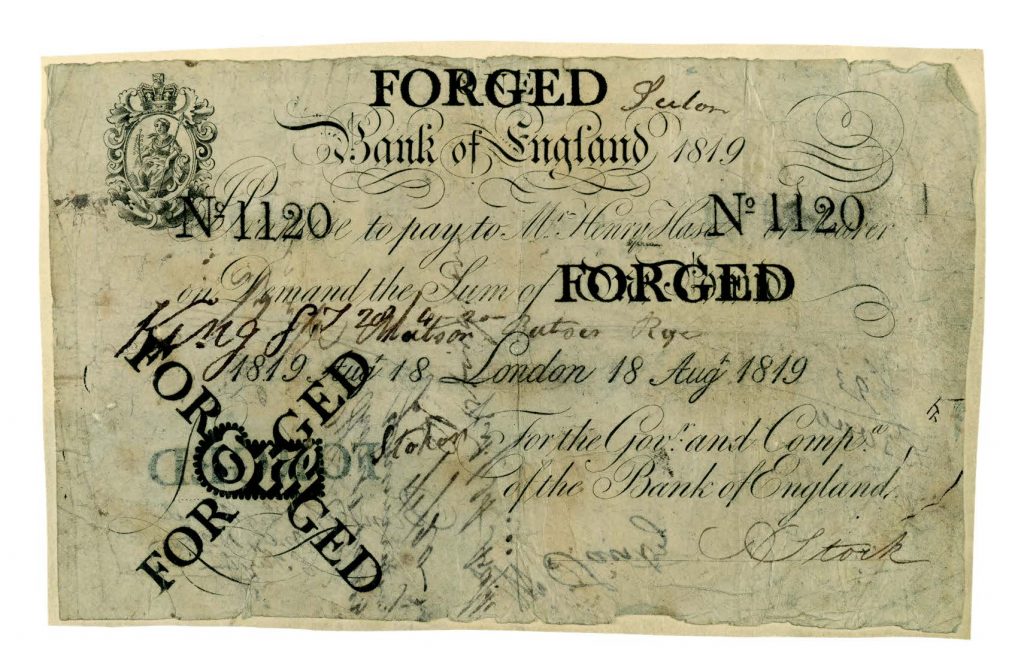

The first money / art crossovers appeared in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Unlike many modern artists, their makers were careful to avoid charges of counterfeiting or defacing legal tender and so created imitative forms of paper money that would not be mistaken for the real thing. One such piece was George Cruikshank’s 1819 Bank Restriction Note (Figure 1). Cruikshank was moved to devise this when he saw the grim scene of two women hanged near the Old Bailey in London. Their crime was ‘uttering’ (passing) forged £1 notes (Figure 2). He delivered a masterful deconstruction and remaking of the banknote as a powerful political statement. Printed on thin bank post paper, the note could be bought for a shilling. The root of the issue lay with the Bank Restriction Act, which was introduced as a financial expedient to support the wars against France. It aimed to keep gold out of circulation and available for government spending and commenced the first large issues of £1 and £2 notes. These low-value notes circulated down the social spectrum and into the hands of less wealthy and less well-educated people. For some, this unfamiliarity with paper money, combined with the fact that they could be so easily forged, led many to fall foul of the law, often unwittingly. In later life, Cruikshank described his Bank Restriction Note as ‘the most important design and etching I ever made in my life for it saved the lives of thousands of my fellow creatures’. He was clearly exaggerating the importance of his work, but the note was famous in its own time and is recognised today as ‘an example of formidably clever satire’.

Radical thinkers

Thomas Spence’s political tokens are well known in British numismatics – he was an important figure in English radicalism of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Growing up in poverty in Newcastle, he was a fervent believer in education as a means to liberation. Spence’s Plan championed land ownership reform, equality and the social dividend. He made use of published books and pamphlets, graffiti, songs, poetry, and an extensive series of political tokens to circulate his agenda, but in a society dominated by aristocratic landowning elites his advocacy of common ownership of land and equality of sexes were considered dangerously provocative. He was arrested for high treason and sedition and spent two periods incarcerated in Newgate jail. One seemingly unique piece is a halfpenny blank bought as part of Gavin Scott’s collection of politically defaced coins. One face shows Spence’s standard punched message ‘SPENCE’S PLAN’ but the other is rather more delicately compelling (Figure 3).

It shows an engraving of a small farm beside a river, the kind of pastoral idyll that Spence’s Plan promised to deliver. The imagery stands in stark contrast to one of Spence’s main series of tokens that depicts an abandoned village, accompanied by the words ‘One only master grasps the whole domain’.

(Above, Figure 3) Thomas Spence (1750-1814), copper halfpenny blank. Fitzwilliam Museum, Presented by Art Fund

For the Cause

A major enquiry which runs through the exhibition is how coins and banknotes have been used to support campaigns against unequal state power structures. Exhibits such as a ‘Votes for Women’ penny provide a powerful commentary on social inequality and the fight for rights and representation from the eighteenth century to the present day, including state violence against peaceful protest, equality and representation, the impact of industrialisation on the skilled working population, monopolies, anti-government and anti-Catholic sentiment, and contemporary protests around the BLM movement. A highlight of the collection is a unique penny stamped to commemorate the Peterloo Massacre. In August of 1819 a crowd of 60-80,000 people gathered at St Peter’s Field, Manchester to demand the reform of parliamentary representation. The grim events of that day are remembered on a uniquely-stamped George III cartwheel penny from the Fitzwilliam collection (Figure 4). The obverse reads ‘HUNT.AND.LIBERTY:’, alluding to the main speaker of the day, Henry Hunt. The reverse reads ‘PETERLOO MURDER AUG 16’, referencing the place and date of what came to be known as the Peterloo Massacre. ‘Peterloo’ was coined by the radical press in mockery of the famous charge of the Household and Union Brigades at Waterloo, but instead depicts the troopers, possibly drunk and certainly out of control, attacking civilians rather than French soldiers.

(Above, Figure 4) George III (1760-1820), copper penny, 1797 Fitzwilliam Museum, Presented by Art Fund

Poverty

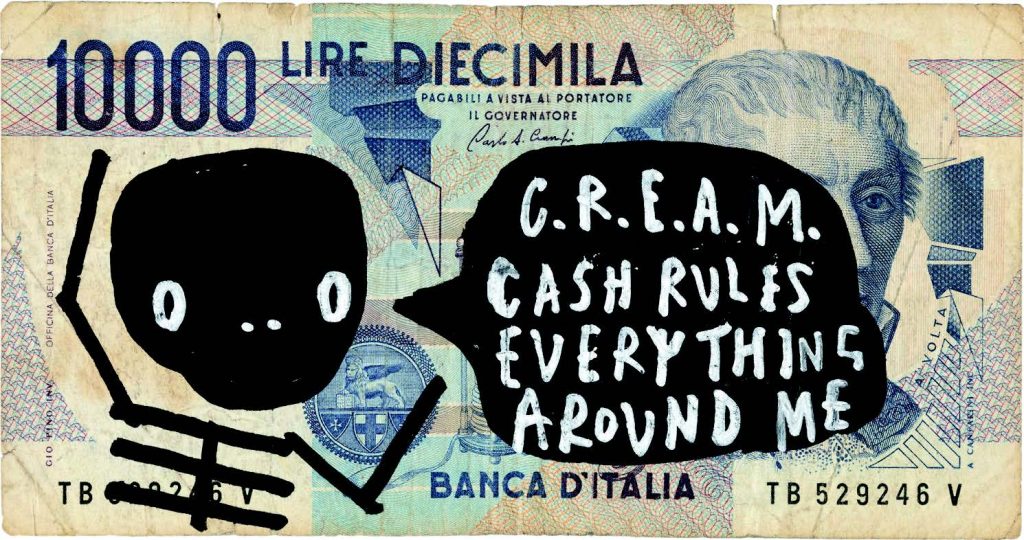

Money is the perfect medium to highlight issues of wealth distribution, including the chasm between those at the top and those at the bottom, and the effects on those living in poverty. Money – both as a physical and theoretical entity – has been used by activists and artists to highlight the links between government policy and the financial and banking systems. A room devoted to the theme of poverty and wealth inequality forms a hinge-point to the exhibition with the spectacular loan of the fragments of an exploded transit van detonated by the HSCB (Hoe Street Central Bank) as part of the Big Bang 2 project which bought up £1.2m of payday loan debt in Walthamstow, London. Other objects in this room include an Occupy George note, one of a series of five designs that used over- stamped infographics to communicate details about economic inequality in the USA. Other interventions are more satirical and not meant for circulation. An example is Skeleton Cardboard’s Dollar Baby which features his signature macabre skeleton figure and recites the chorus of the Wu- Tang Clan’s classic 1994 track (Figure 5).

War Machine

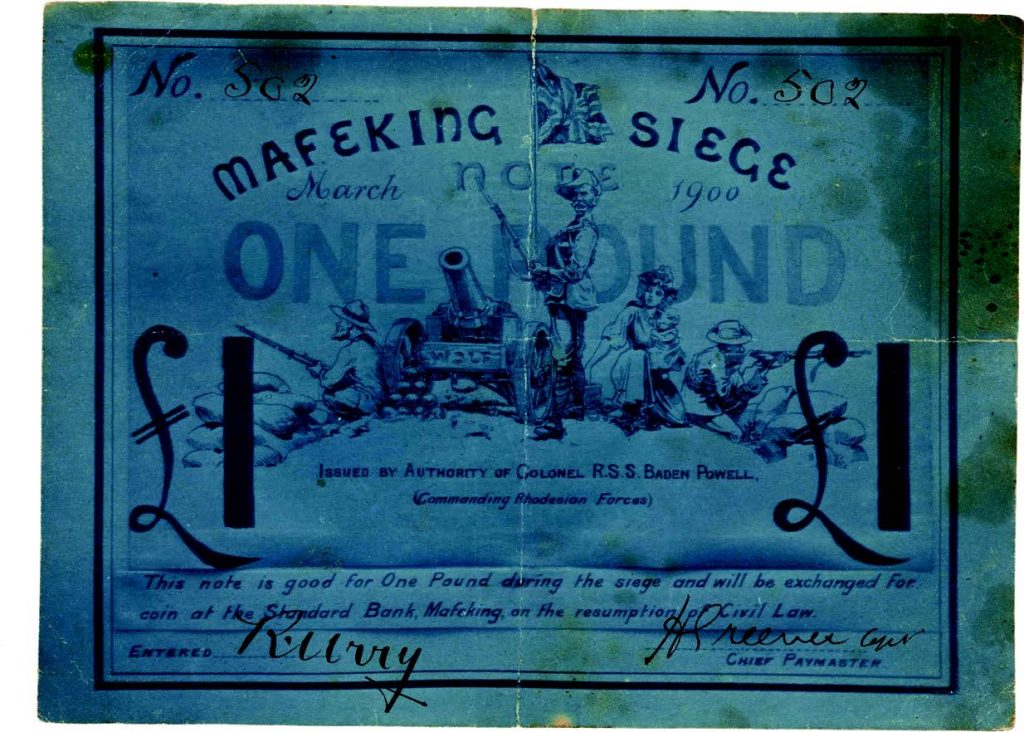

The monetary responses to, and consequences of, conflict are highlighted in the exhibition. The first looks at monetary and other objects that reflect the experiences of individuals caught up in war. These range from engraved coins from the Napoleonic Wars to loot taken in the Mahdist

War to WWI objects of commemoration. A section looks at emergency money with emphasis on the Siege of Mafeking and the Boer War – the siege of Mafeking notes designed by Baden-Powell remain a sought-after memento of this conflict. The exhibition will bring together, for the first time, the money from the siege (Figure 6), the sketches made by Baden-Powell for the notes, and the Wolf Gun itself, which was central to the design of the Mafeking £1 note.

Monetary material made for use in PoW, internment and concentration camps is also considered, and includes some of the token notes made as illusory incentives for inmates like this piece from Ravensbrück, the largest Nazi concentration camp for women, located north of Berlin (Figure 7). The final group of material contrasts experiences of occupation and resistance in WWII through notes made by the occupying power and those guerrilla and other groups who fought back or subverted the system using the symbolism of coins and notes

Extreme Ideology

Defaced! considers acts of defacement in extremism. It contrasts pro-Franco fascist and rival anarchist CNT coins made during the build up to the Spanish Civil War. Communist and fascist sentiments were also stamped on UK coins from the late 1930s with swastikas applied to Britannia’s shield or a hammer and sickle crudely stamped over her image. A wide range of rival sectarian stamps and slogans from Northern Ireland made during the 1970s to 1990s reveal the widespread use of coinage as a means of everyday intimidation, identity and affiliation. The majority of those in the collection show loyalist slogans such us ‘UVF’, stamped on Irish coins for the Ulster Volunteer Force. Republican examples are UK coins typically stamped with ‘IRA’. One example references a darkly sinister period from the Troubles: a two pence coin has been stamped ‘Smash H Block’ over the bust of the queen – ‘Smash the H Block’ was a particularly well-known slogan that supported political prisoners’ protests at Long Kesh / Maze prison. This defacement was made during the 1981 hunger strike in which ten Republican prisoners starved themselves to death. International interest was drawn when the leader of the strike, Bobby Sands, was elected as a Member of Parliament.

Money Art

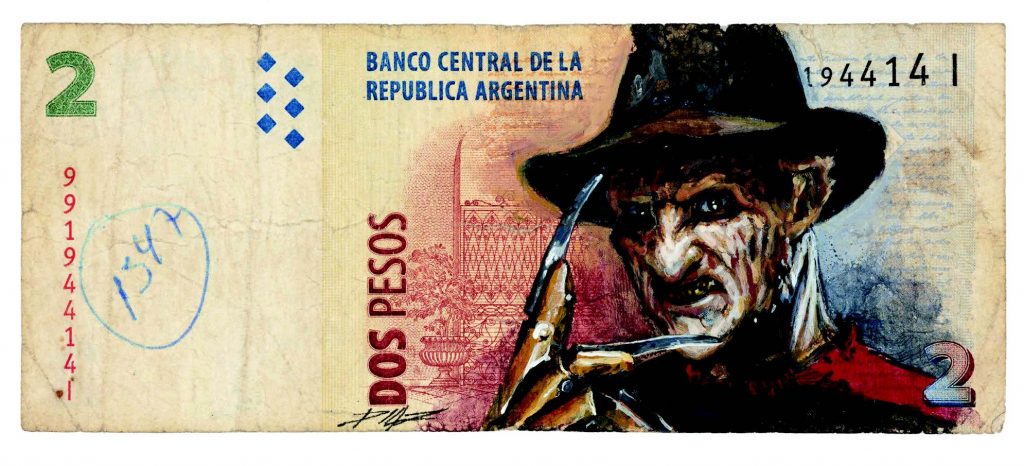

The final sections of the exhibition consider the role of money as a raw material, a canvas and an inspiration for artistic and political interventions. Artists like JSG Boggs and Akasegawa Genpei came into conflict with the law for their money art. Other artists, like Luis Orlando Ortega use worthless paper bills to make street art sculptures to sell. The illustrator Sergio Guillermo Diaz uses Argentinian banknotes as a canvas for his accomplished sci-fi, fantasy and horror portraits (Figure 9) – on this example Freddy Kreuger replaces the image of Lieutenant General Bartolomé Mitre. The two pesos note above was demonetised in June 2018 after periods of inflation and replaced by a coin. Diaz follows fellow Argentinian artist Ral Veroni, who began drawing on deflationary banknotes in 1994.

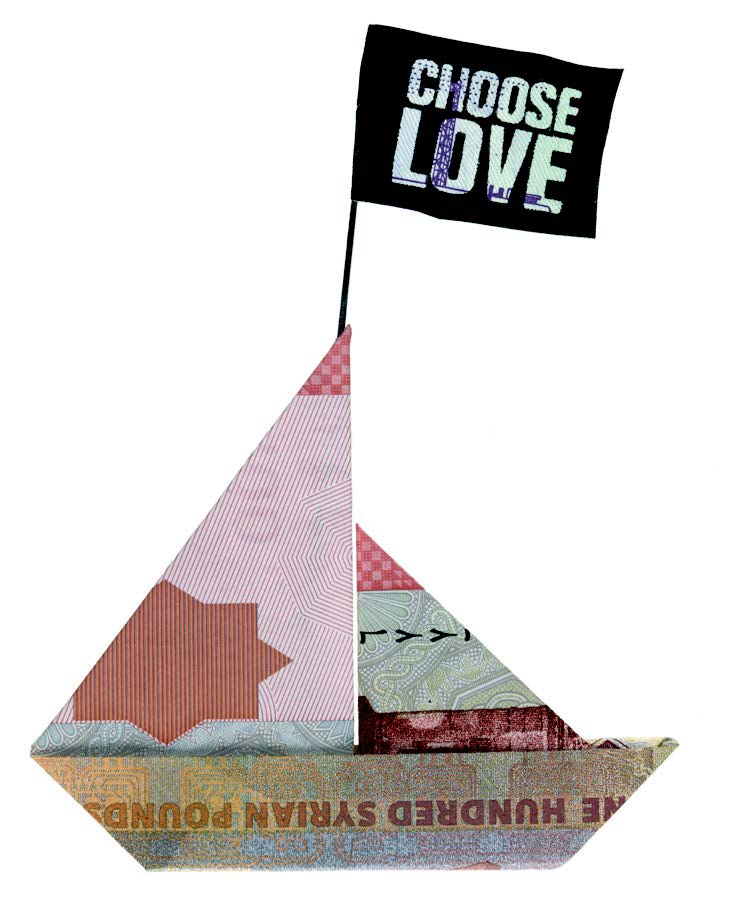

A section towards the end of the show focuses on a case study of money objects relating to the refugee crisis. It begins with the causes of displacement shown by Issam Kourbaj’s Hit Hard piece featuring holed banknotes and beaten coins, to the methods of transit, revealed by Aida Wilde’s Dream Boat II origami banknote made from a Syrian 100 pounds note. It concludes with notes from refugee camps in Greece, and the reception of refugees in host countries exemplified by the controversial ASPEN credit card given to asylum seekers in the UK.

The exhibition concludes by questioning the future of money defacement in an increasingly digital monetary environment. These ten objects are just a sample of more than 180 coins, banknotes, banners, artworks and other objects that will feature in the exhibition, which will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue edited by the author.

Kevin Clancy’s book Objects of War: currency in a time of conflict is available from Spink Books, www.spinkbooks.com, or by emailing [email protected].