LEAMINGTON TENNIS COURT CLUB AND ITS FOUR VC'S

When the club opened on 29th December 1846, its name was ‘The Tennis Court Club’. It sat among the town’s many attractions which made Leamington a popular holiday and retirement venue.

Leamington had fine houses, hotels with nightly Masters of Ceremonies, theatres, clubs, societies, archery, rowing, cricket, point-to- point racing and hunting and, of course, the spa waters. The Leamington Courier recorded weekly the aristocratic arrivals.

The Club, which was compared to Whites and Boodles, held to earlier Georgian values – for example being open until 2am, then having fines rising until 8am. Drinking, smoking, billiards and cards prevailed, and it listed some prominent names among its membership

Hon Colonel George Cathcart

(later General Hon Sir George Cathcart GCB)

He was born in Renfrewshire, son of William Cathcart, 1st Earl Cathcart. After receiving his education at Eton and in Edinburgh, he was commissioned into the Life Guards in 1810. In 1813 he went to Russia to serve as aide-de-camp to his father, who was Ambassador and military commissioner. George Cathcart was present at the battles between the Russian and the French armies in 1813 and he followed the Russian army through Europe, entering Paris in March 1814.

When Napoleon returned in 1815, Cathcart served as aide-de-camp to the Duke of Wellington and was present at the battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo. After the war he was commissioned in the 7th Hussars, and promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1826. He then joined the 57th Regiment in 1828, the 8th Hussars in 1830 and the 1st Dragoon Guards in 1838. Cathcart was promoted to colonel in 1841.

In 1852 to 1853, as Governor of the Cape of Good Hope, he granted the first constitution to the colony, ended the 8th Cape Frontier War and crushed the Basutos. In 1853 he was appointed Adjutant-General to the Forces.

He chaired significant meetings of the Club, before being called up at the start of the Crimean war, appointed to command the 4th infantry division. The British government gave him a “dormant commission” which meant that if something were to happen to Lord Raglan, Cathcart would take command.

General Cathcart’s death at Inkerman: he took command of the 1st Brigade for the Battle of Inkerman and was shot through the heart while charging up a hill with a company of men from the 20th Regiment of Foot on 5th November 1854.

Lieutenant-General James Thomas Brudenell,

7th Earl of Cardigan, KCB (1797 –1868)

Lieutenant-General James Thomas Brudenell, joined LTCC in 1847 when the 11th Hussars were billeted in nearby Coventry. He was the officer who commanded the 11th Hussars Light Brigade during the Crimean War. He led the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava.

Throughout his life in politics and his long military career he characterised the arrogant and extravagant aristocrat of the period. His progression through the Army was marked by many episodes of extraordinary incompetence, but also by generosity to the men under his command and genuine bravery. As a member of the landed aristocracy he had actively and steadfastly opposed any political reform in Britain, but in the last year of his life he relented and came to acknowledge that such reform would bring benefit to all classes of society.

In 1823 while he was in Paris, Brudenell met and fell in love with Elizabeth Johnstone, the wife of a Captain Johnstone, who had left her husband. The pair eloped and set up house at Versailles. In June 1824 Captain Johnstone started the divorce process; Brudenell did not offer any defence and did not appear at the court hearing. Johnstone was awarded £1,000 (equivalent to £100,000 today) in damages. After the trial, Brudenell offered to ‘give satisfaction’ to Johnstone, by fighting a duel. Johnstone was reported as saying, “he has already given me satisfaction: the satisfaction of having removed the most damned bad-tempered and extravagant bitch in the kingdom.” She and Brudenell were married – she was promiscuous, extravagant and bad-tempered and the marriage was a disaster. There were no children born to the couple.

In 1854 the Crimean War broke out; the 57-year-old Cardigan was sent out in command of a cavalry brigade in Major-General Lord Lucan’s division. When the cavalry camped outside Balaclava, Lord Lucan lived alongside the men while Cardigan dined and slept aboard his luxurious yacht in the harbour. Cardigan led the Light Cavalry into the ‘Valley of Death’ in the charge of the Light Brigade; he was the first in and the first out of the attack on the Russian guns and was unscathed.

He insisted on being regarded as a hero for the rest of his life. After the war he lived at Deene Park, his Northamptonshire seat, where he died from injuries caused by a fall from his horse on 28th March 1868.

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Duberly

He served in the Crimean campaign of 1854– 55 with the 8th Hussars, including the battles of Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman and Tchernaya, affairs of Bulganak and M’Kenzie’s Farm, and siege of Sebastopol (Medal with four Clasps, and Turkish Medal). Served in Rajpootana and Central India in 1858–59, including the capture of Kotah, reoccupation of Chundaree, battle of Kotah ke Serai, capture of Gwalior, actions of Kooudrye and Boordah (Medal with Clasp).

The Charge of the Light Brigade October 1854 – a troop of the 8th Hussars, under Captain Duberly, had been detached to act as escort to Lord Raglan.

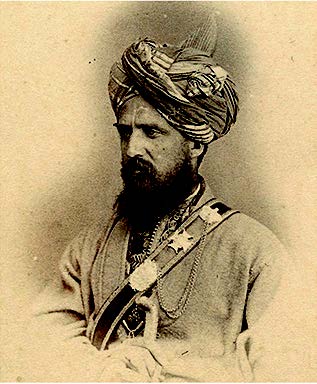

PIC Title - Captain Henry Duberly,

Paymaster of the 8th (The King’s Royal Irish) Light Dragoons (Hussars) and Mrs Fanny Duberly, 1855.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Forrest, 4th Dragoon Guards, wrote of Fanny’s conduct in the Crimea, “They say she is not actually a ‘bad one’ but that she behaves in the most extraordinary way, riding and walking about with anybody, giving men every encouragement to flirt with her, but when the gentleman becomes rather too ardent in his admiration, she suddenly says ‘why you must forget that I am a married woman. I shall tell my husband of this, and we shall have such a laugh.’ They say that she has played this trick to several.”

Fanny Duberly led one of the most dashing and dangerous lives of the mid-nineteenth century. In 1854, while still in her early twenties, Fanny accompanied her husband Henry and his regiment to the front lines of the Crimean War to fight the Russians. Considered the first female ‘embedded reporter,’ Fanny’s eye- witness account of the horrors of the Crimean War includes the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade. After having survived bullets, cholera and shipwreck, Fanny and her husband next saw action in India. In 1857 Fanny rode more than two thousand miles through the deserts of India alongside Captain Duberly and his troops during the suppression of the Sepoy Revolt.

Lieutenant Colonel Unett of 3rd Light Dragoons

Long term club committee member Captain Unett led the ‘Greys’ squadron of HM 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons at the Battle of Chillianwallah, Second Sikh War, on 13th January 1849.

Chillianwallah was an iconic battle for the British cavalry for widely differing reasons. Unett’s charge with his squadron of the 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons on the left flank was held up as a paragon. The squadron was mounted entirely on greys. From Unett’s squadron of HM 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons of 106 men, only 48 were in the saddle at the end of the battle. Commanders at the Battle of Chillianwallah were Major General Sir Hugh Gough against the Sikh general, Shere Singh. Size of the armies at the Battle: 12,000 British and Bengalis with 66 guns against 35,000 Sikhs with 65 guns.

On the regiment’s return to England, Captain Unett and Lieutenant Stisted, both wounded in the battle, were presented to Queen Victoria to be congratulated on their conduct.

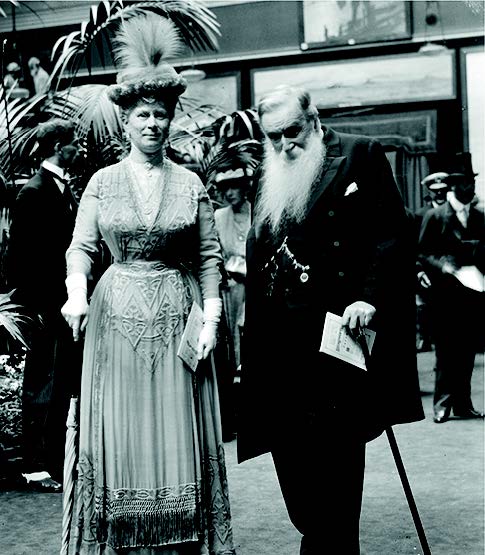

General Sir Dighton Macnaghten Probyn, (1833–1924)

VC, GCB, GCSI, GCVO, ISO, PC

In 1857 the squadron of 2nd Punjab Cavalry which Probyn commanded was frequently referred to as Probyn’s Horse. (It is now part of the Pakistan Army and officially designated as 5 Horse.) Probyn was ‘Mentioned in Despatches’ many times for his actions.

Probyn was 24 years old when the following deeds took place for which he was awarded the VC:

‘At the battle of Agra, when his squadron charged the rebel infantry, he was some time separated from his men, and surrounded by five or six sepoys. He defended himself from the various cuts made at him, and before his own men had joined him had cut down two of his assailants. At another time, in single combat with a sepoy, he was wounded in the wrist, by the bayonet, and his horse also was slightly wounded; but, though the sepoy fought desperately, he cut him down. The same day he singled out a standard bearer, and, in the presence of a number of the enemy, killed him and captured the standard. These are only a few of the gallant deeds of this brave young officer.’ Despatch from Major-General James Hope Grant, KCB, dated 10th January 1858.

In 1872 the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, appointed him as one of his equerries. He was in later life an ornament of the Victorian age, being Keeper of the Privy Purse. This was an important position as the Prince and Princess were both profligate in spending. Probyn was totally devoted to the Princess, then Queen-Empress, building gardens for her at Windsor Castle and Sandringham House. The Queen returned the devotion, carrying round a knife with her to cut open his collar when he occasionally had seizures.

His VC sold at auction on 24th September 2005 for £160,000.

Probynabad, a town in the Punjab province of Pakistan with large farmlands owned by the regiment, is also named after him.

MAJOR GENERAL SIR CHARLES CURETON KCB

(1826–1891)

He served in the First Anglo-Sikh War, and was present at the battle of Aliwal on 28th January 1846, receiving the medal and clasp. In the Second Anglo-Sikh War he was aide-de-camp to his father until the latter’s death at the battle of Ramnagar in November 1848. He took part in the passage of the Chenab River on 2nd and 3rd December, in the battle of Gujrat on 21st February 1849, and in the pursuit, under Sir Walter Gilbert, of the Sikh army, the capture of Attock, and the occupation of Peshawar, receiving the medal and clasp. Cureton served in the north-west frontier campaigns of 1849 to 1852, including the operations against the Baizai (1849), and the Mohmand Expeditions (1851– 2), receiving the medal and clasp. On 4th May 1852, he was appointed second in command of the 2nd irregular cavalry. He took part in the suppression of the Sonthal rebellion in 1856, and in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. He served against the Sealkote mutineers and took part in the action of Trimu Ghat, also against the Gogaira rebels. He raised and commanded PIC – Cureton’s Multani cavalry, and continued to command it after it became the 15th Bengal cavalry. He served with it, and had charge of the intelligence department throughout the campaigns in Rohilkhand and Oude in 1858 and 1859. He was 11 times mentioned in despatches published in general orders and received the medal and brevets of major and lieutenant-colonel. He served in the north-west frontier campaign of 1860, and on 2nd June 1869 was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB), military division. For five years, from 22nd October 1879, Cureton commanded the Awadh division of the Bengal Army. He was promoted to be Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), military division, in May 1891. On joining LTCC, in 1872 his address was ‘Hampton Court’! He visited the club many times.

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB

(1833-1885)

Also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, or Gordon of Khartoum, General Gordon saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in the British Army. However, he made his military reputation in China, where he was placed in command of the ‘Ever Victorious Army’, a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname ‘Chinese Gordon’ and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British. Li Hongzhang, the governor of the Jiangsu province said, “He is a glorious fellow! … With his many faults, his pride, his temper, and his never-ending demand for money (to pay his soldiers in order to prevent looting) – but he is a noble man, and in spite of all I have said to him or about him, I will ever think most highly of him … He is an honest man, but difficult to get on with.” During his time in China, Gordon was well known and respected by friend and foe alike for leading from the front and going into combat armed only with his rattan cane (he always refused to carry a gun or a sword). During his time with the Ever Victorious Army, Gordon had won 33 battles in succession.

Back in Britain in 1865, Gordon commanded the Royal Engineers’ efforts around Gravesend, Kent, to erect forts for the defence of the River Thames. He was much involved in charity work, trying to ensure that homeless boys he found begging on the street did not go hungry while attempting to find them homes and jobs. Every year, Gordon gave away about 90% of his annual income of £3,000 (equivalent to £333,000 in 2022) to charity.

He entered the service of the Khedive of Egypt in 1873 (with British government approval). After meeting Gordon in 1874, the Khedive Isma’il had said, “What an extraordinary Englishman! He doesn’t want money!” He later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the local slave trade. Exhausted, he resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

A serious revolt then broke out in the Sudan, led by a Muslim religious leader and self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. In early 1884 Gordon was sent to Khartoum with instructions to secure the evacuation of loyal soldiers and civilians and to depart with them. In defiance of those instructions, after evacuating about 2,500 civilians he retained a smaller group of soldiers and non-military men. Besieged by the Mahdi’s forces, Gordon organised a citywide defence that lasted for almost a year and gained him the admiration of the British public, but not of the government, which had wished him not to become entrenched. Only when public pressure to act had become irresistible did the government, with reluctance, send a relief force. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

Copies of Tennis the Leamington Way are available at £70 each. Please contact the author for further details by emailing [email protected].