THE CASE OF THE NAXOS COIN

By Tim Wright

Masterpiece

Coin auction catalogues are a delight, even if they quickly consume our bookshelves. Beautifully presented, sometimes even in hardback, they’re not out of place on the proverbial coffee table. Whilst the photography is always stunning; the real art is in the descriptions of the lots. There are few that are not one of the best-known examples in a condition invariably described as Extremely Fine, apart from obvious flaws. Any provenance is trumpeted in all its biographical glory, and where it is thin, it is substituted by an extensive description of the type: the artistry, the engraver, the historical backstory and more. Invariably, it is concluded that the lot in question is a Masterpiece, which then lives up to its name and sells for stratospheric sums at auction, thus encouraging even more superlatives the next time.

“Not every highly priced coin is a masterpiece, even if real masterpieces are extremely expensive given the laws of supply and demand.”

Coin dealers and auction houses may be forgiven a degree of grade inflation and poetic license, but behind these words are two important questions: What constitutes a numismatic masterpiece, and how does this relate to the price placed on it by the market? Some might argue that the definition of a masterpiece is that it is priceless. Others may suggest that those who know the price of everything know the value of nothing 1. Both make for witty aphorisms but do not reflect reality that price reflects perceived value. Not every highly priced coin is a masterpiece, even if real masterpieces are extremely expensive given the laws of supply and demand.

Six years ago, I witnessed something extraordinary at one of my first ancient coin sales. Not yet familiar with the dynamics of the auction room, I was immediately absorbed in the rapid passage through the lots. After a while, the pace changed, and everyone’s attention was focused on the dual between the remaining two bidders. When the coin hammered for more than £500,000, there were gasps and applause; collective relief that the market was in rude health. Dealers began to recount stories of their encounters with this coin type: the dealers, collectors, museums and auction involved in its long history. That coin was the illustrious 460 BCE Tetradrachm from Naxos, Sicily.

I was intrigued. I read through the auction catalogue and went online to find other examples of this type also selling for high prices. The descriptions reinforced the idea that this was a special coin of great beauty and rarity, with an historic pedigree that furthered the allure. I bought a worn copy of Herbert Cahn’s eighty-year-old book on the coins of Naxos2 , and with my schoolboy German was able to appreciate his die-study of the entire series. I decided to track down every known example and, where possible, visit, view and hold them in hand.

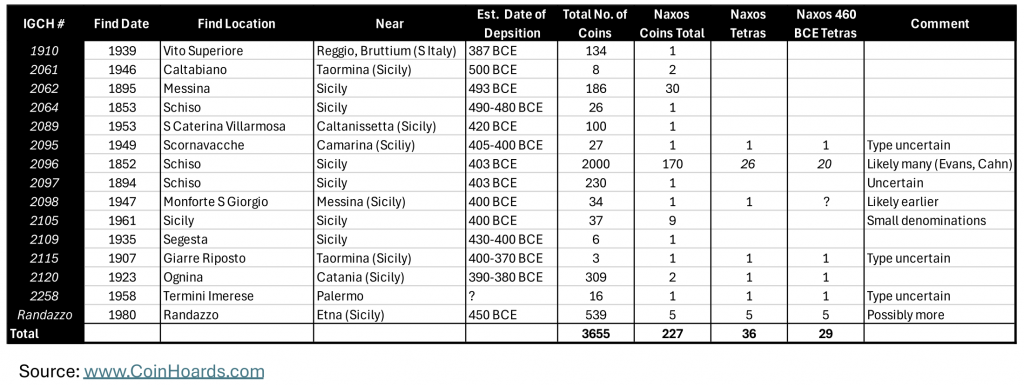

Rarity

A Masterpiece is usually singular. As far as we know, there is only one version of the Mona Lisa. In the case of coins, there are a few like the Aetna Tetradrachm where there is but one known example. In most cases thousands of coins3 were struck from a die-pair, of which tens or hundreds have survived mainly through hoards. Due to the excellent work of the American Numismatic Society (ANS), the Royal Numismatic Society (RNS) and others, we have a consolidated view of these4. Fifteen hoards have yielded over two hundred Naxos coins, including around thirty examples of the c. 460 BCE tetradrachm [Fig. 1]. Most of these are concentrated in the hoards of Schiso from 1880 and Randazzo in 1980. Regrettably not all hoards or finds are documented, and Cahn’s work identified almost twice this number, half of which were in museums5.

“Eighty years after Cahn the museum examples have grown to thirty-two, but this has been outstripped by those in private collections”

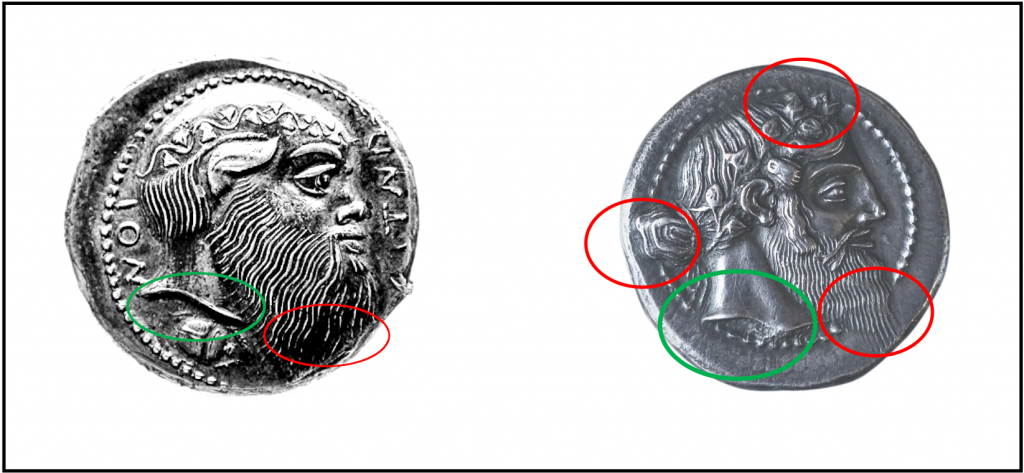

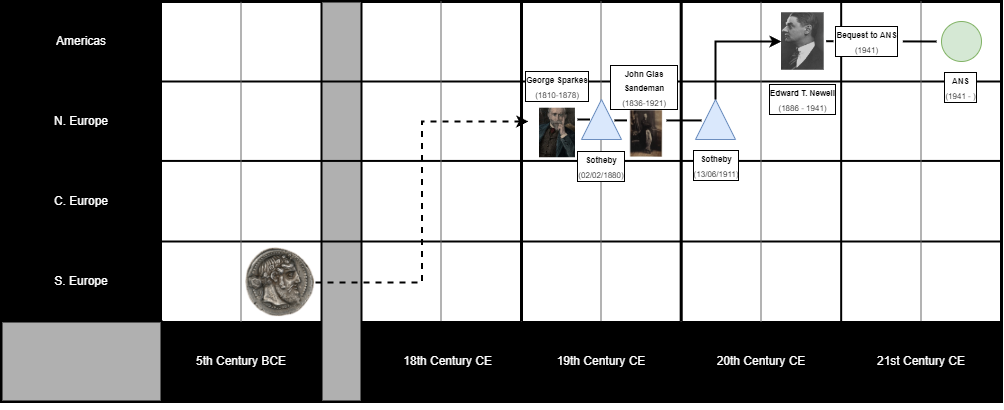

Eighty years after Cahn the museum examples have grown to thirty-two, but this has been outstripped by those in private collections, producing a total of sevent-yeight [Fig. 2]. For most, if not all, it is possible to gather information on their history of ownership, price at auction, and condition. As we will see, condition is an important driver of price paid, and there is a broad spread of quality in terms of the known examples. This is partly due to the progressive appearance of a die-break during the production process [Fig. 3], which Cahn puts down to issuers not wanting to substitute the die6. So, considering rarity as a factor, perhaps it is the engraved die that should be considered the potential masterpiece?

Art

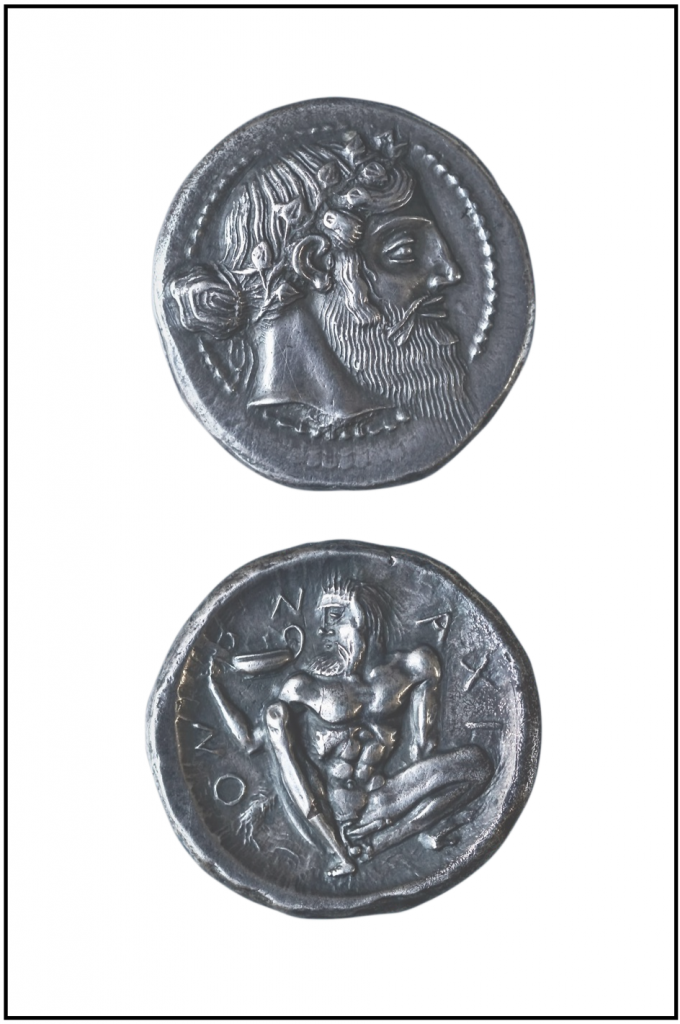

If we turn to the coin itself, we are immediately struck by its extraordinary artistry [Fig. 4]. The obverse portrays Dionysus, the god of wine, hardly recognisable but for his give-away garland of ivy. The image is all the more distinct for the control exerted over this fun-loving deity, with a neatly groomed beard, whiskers and moustache and the most serious of expressions. The image has been described as the severe Dionysus.

The reverse portrays his companion Silenus crouching naked, with a brazen erection and drinking from a wine cup or kantharus. The innovation here is in the complexity of the pose; the balance achieved, and the perspective provided through foreshortening. Cahn highlights the transition from an archaic to a classical style. The work is attributed to the Aetna Master, the engraver of the singular surviving coin found only in the KBR (Belgium National Library). The key similarities noted are the truncated neck (almost statue-like) and the image breaking through the beaded boundary [Fig. 5].

We can only speculate as to the intentions of the engraver, and what he sought to convey to his audience. At one level, he was maintaining continuity with the patron-God of Naxos, as found on earlier drachma coins, and adding Silenus, images of whom on broken pottery are strewn across the remains of the city7 . Yet there was a message in the radical change of style: either he was delivering on a very specific brief of his client (the issuing authority of Naxos), simply showcasing his virtuosity as an artist, or perhaps something of both.

History

Without contemporary narrative, it is questionable whether we can even describe material culture as ‘art’8. In the case of Naxos, we have three types of sources to draw on to understand the historical context for the Naxos coin: classical writers, archaeological remains, and the coins themselves. Naxos features in the accounts of Thucydides, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Polynaeus, Pliny the Elder and Pausinius, all but two of whom were writing centuries after the key events. The archaeological remains were only excavated in the 1960s from among the citrus groves of Giardini in the Schiso peninsula. Cahn’s study identified around six hundred surviving examples of a hundred of such coin types.

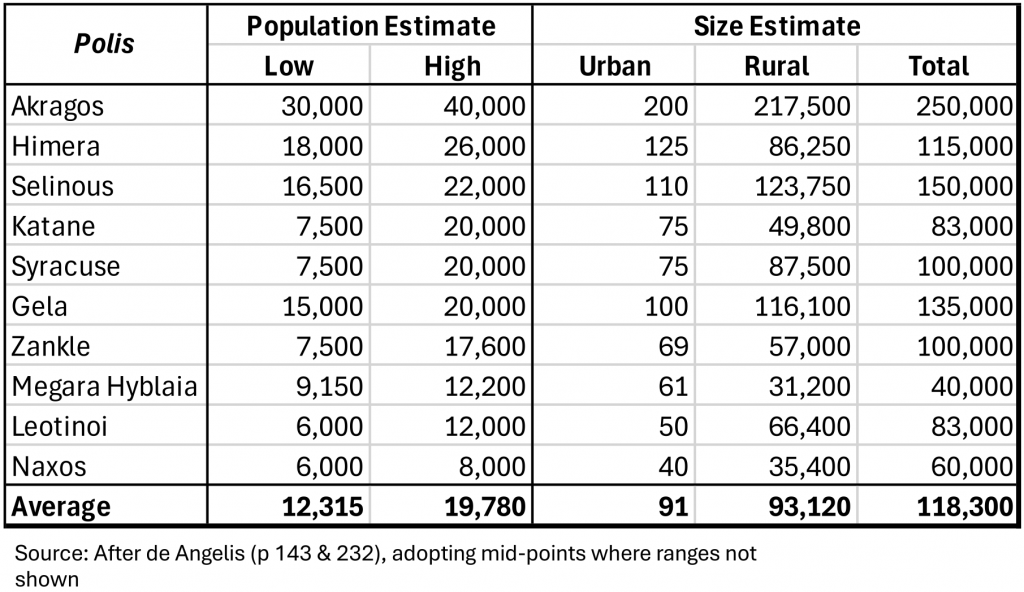

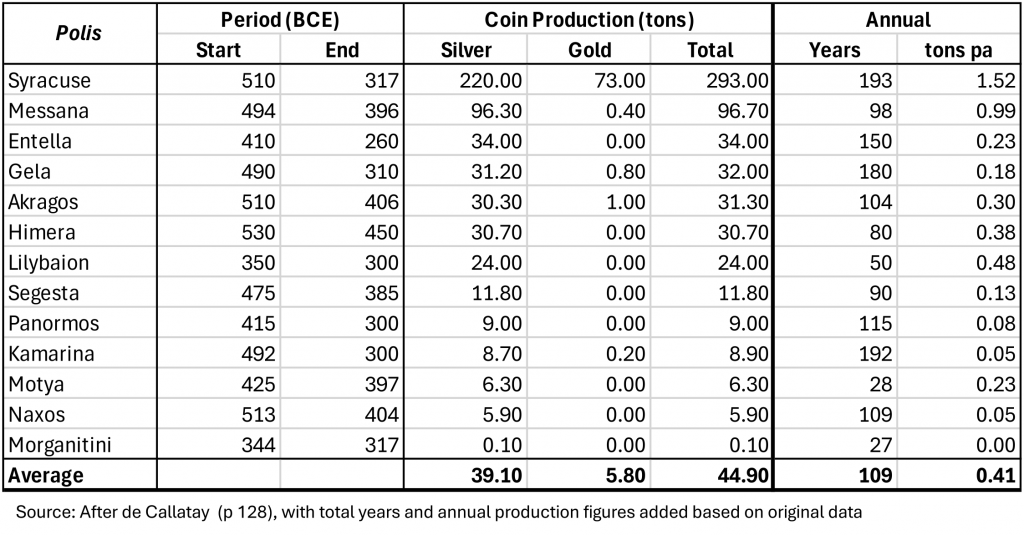

The classical sources tell us about the city’s foundation under Theokles, as the first Greek settlement in Sicily in the late-eighth century BCE. The city started as a small settlement of ten hectares expanding to forty, which were destroyed and rebuilt with the addition of some dockyards for trade. The city was repeatedly occupied, with its citizens exiled and then allowed to return, although ultimately defeated and enslaved. Its population made it the smallest of the Greek Poleis, at 6-8,000 [Fig. 6], matched by one of the lowest estimated levels of coin production [Fig. 7].

So how do we reconcile ‘little Naxos9’ with its huge impact numismatically? Thucydides tells us that the city’s status as the first in Sicily was recognised through the creation of an altar of Apollo Archeaetes, where delegations from other cities made sacrifices before leaving for the Greek mainland10. This made the city important, so we may speculate that when its population returned from their enforced exile, they wanted to produce a coin to reflect that rebirth.

Economics

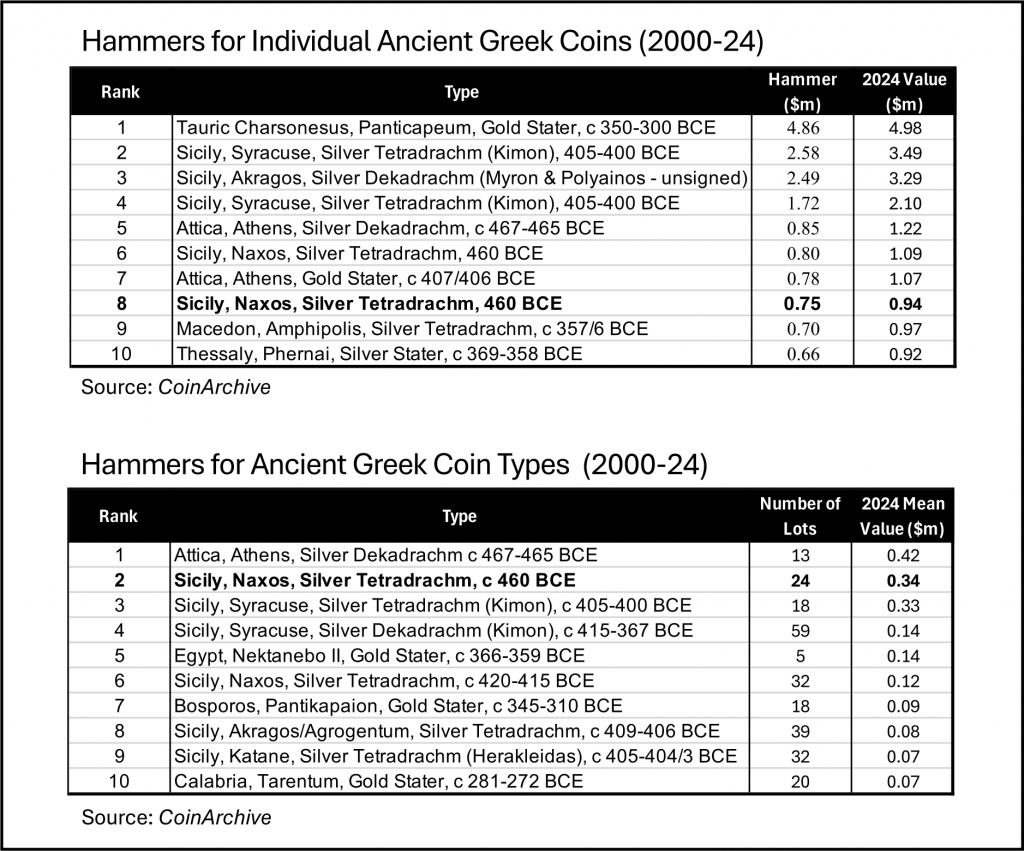

The rarity, artistry and historic backstory of the Naxos coin helps to explain why it is considered both a masterpiece and has achieved extraordinary prices at auction. How does this compare with other ancient Greek coins and has this changed over time? A simple league table of the highest selling ancient Greek coins places the Naxos coin eighth in the rankings, but if we remove one-of-a-kind coins and focus on those selling more than ten examples, the Naxos ranks second only to the Athenian decadrachm [Fig. 8].

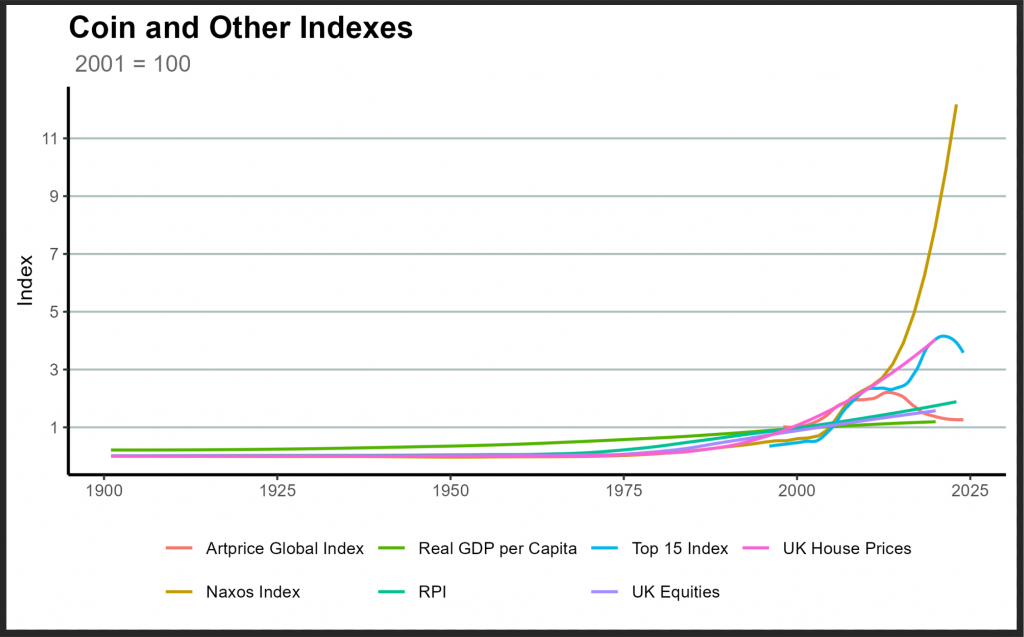

Two hundred years ago, gentlemen collectors could afford to buy the Naxos tetradrachm for around £5-6, roughly £500 in today’s money; at the time a fifth of an average annual wage or a sixtieth of an average house price. Gentlemen or not, today’s collectors have been priced out of the market as the cost has risen to over £400,000: twelve times the average wage and one-and-a-half times the average house price. Collecting of this type has reverted to modern princes, millionaires or even billionaires (see Fig. 12). Like art and other collectables, ancient Greek coins have experienced massive asset inflation [Fig. 9].

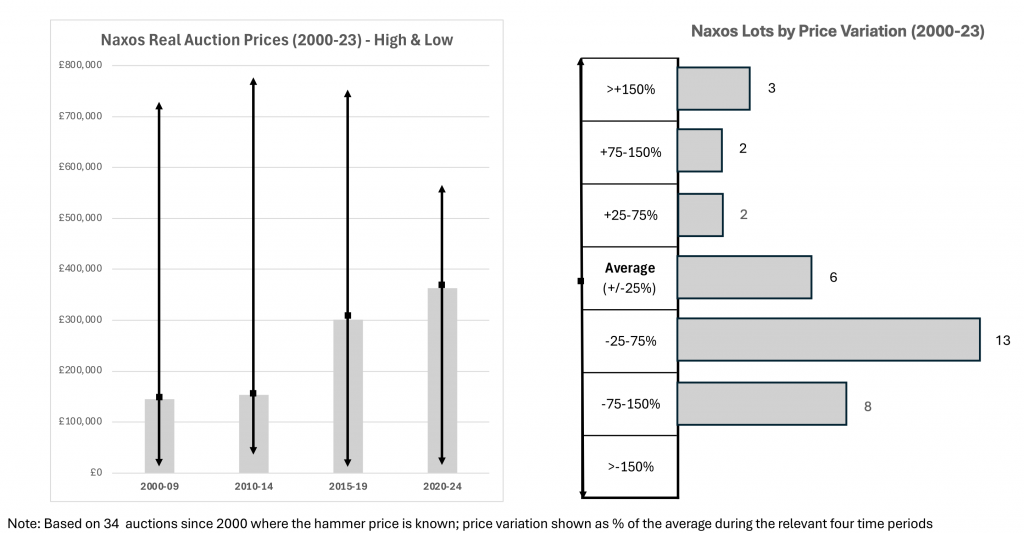

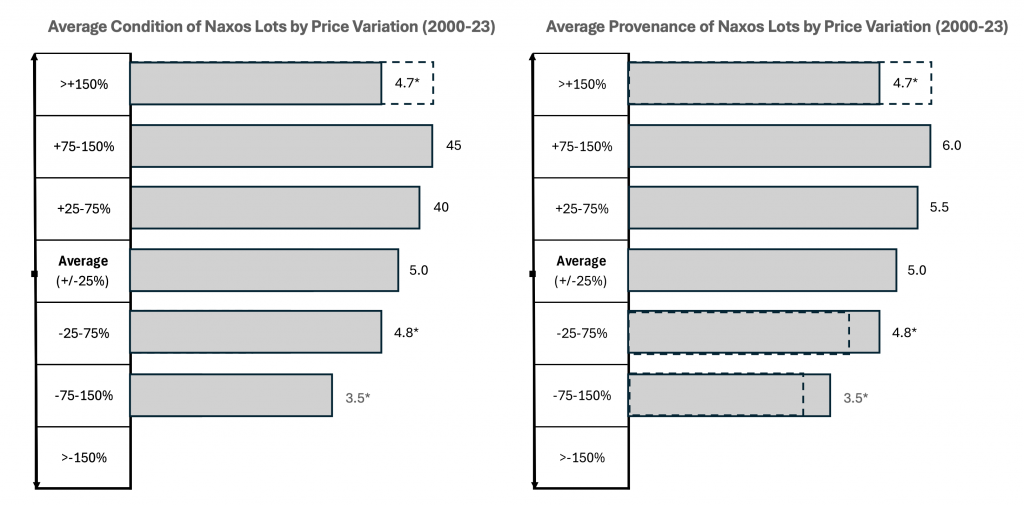

The principal drivers of price have therefore been the desirability of different coin types, no doubt influenced by their artistry and historical backstory, as well as the rising tide of the market. But even for any given Naxos coin at points in the market, there is substantial in the auction prices achieved [Fig. 10]. Such variations appear to be driven principally by condition, but also by provenance, with the latter becoming increasingly important given the scrutiny the regulators place on illegal looting and trafficking [Fig. 11].

Provenance

Whilst the Romans clearly valued and collected Greek antiquities, there is no firm evidence that they collected ancient coins from this period, despite the habit of Augustus giving ancient tokens to dinner guests11. The real mania for collecting started in the early-Renaissance, with the likes of Petrarch buying from peasants tilling the fields12. The audience were princes, who added these to their cabinets of curiosities13. Of greatest interest were coins depicting Roman emperors who could provide inspiration for their successors14. Greek coins surely followed, although it would not be until the eighteenth century that we find explicit reference to the Naxos coin, possibly because of earlier attribution to the Cycladic Island of the same name15.

Figure 12. Collectors: Aristocrats, Industrialists & Financiers

Torremuzza (1727-1794)

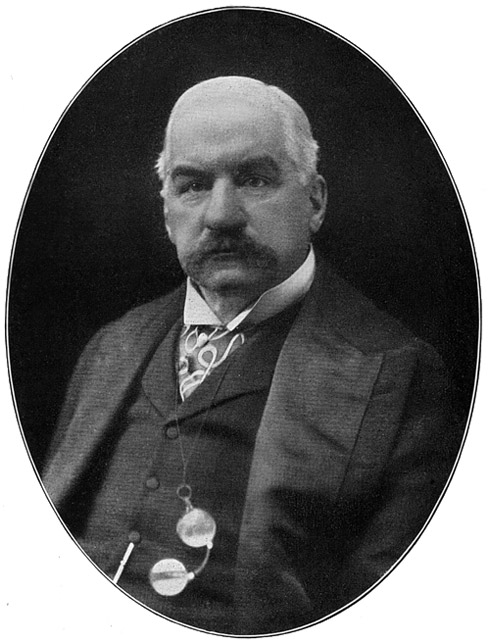

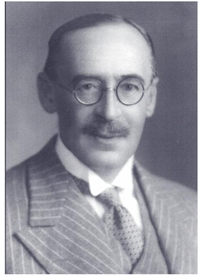

Coin collecting has been described as the ‘Hobby of Kings’. Beyond the inspiration of Roman Imperial forebearers, we can only speculate as to the motivation for collecting and the impact of coins like the Naxos tetradrachm. The desire to impress courtiers and guests with taste, wealth and power may have played a part16. Such motivations would continue to play a part in the new aristocracy of industrialists, oil tycoons, and financiers from the nineteenth to twentieth centuries [Fig. 12].

The nineteenth century also saw a democratisation of ancient coin collecting, to include ‘gentlemen collectors’ drawn largely from the professions and the clergy [Fig. 13]. No doubt there was an element of emulating the ‘princes’ but the mainstreaming of numismatics likely reflects the influence of education, not least the Grand Tour, which increasingly became available to the upper middle classes17. As the habit of collection spread, we also see the travels of the Naxos tetradrachm, from Sicily and Europe to North America [Fig. 14].

Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Figure 13. Collectors: Clergy, Physicians, Lawyers & Architects

Crime

Last year, the headlines regarding the owner of a London auction house being arrested in New York sent shockwaves through the numismatic community18. Eight months after his arrest, the British coin dealer has confessed to knowingly trafficking and misrepresenting a Brutus Eid Mar gold aureus, a Naxos tetradrachm and a number of Alexander decadrachms from the Gaza Hoard19. The Naxos coin was purchased from a known tomboroli (tomb-raider) in Sicily and then auctioned with a false provenance. Recently, the coin was also recovered as part of a group being smuggled into the US and has since been repatriated to Italy along with other looted artefacts.20

We know from the exposé of the Medici Conspiracy that there is a highly developed system for looting, transferring, laundering, selling and collecting antiquities21. Thus, what we see with the Naxos coin is almost certainly the tip of the iceberg in terms of illegal activity. As mentioned previously, only a limited number of Naxos coins have been documented among hoards, the latest of which was the Randazzo Hoard of 198022. The fact that at least twelve of the additional examples identified since Cahn have only recent or no provenance reinforces the probability that all these came to market illegally. It is likely that most examples have been looted, although only the most recent activity is considered truly in violation of local or international rules (see Fig. 2 for the additional examples found).

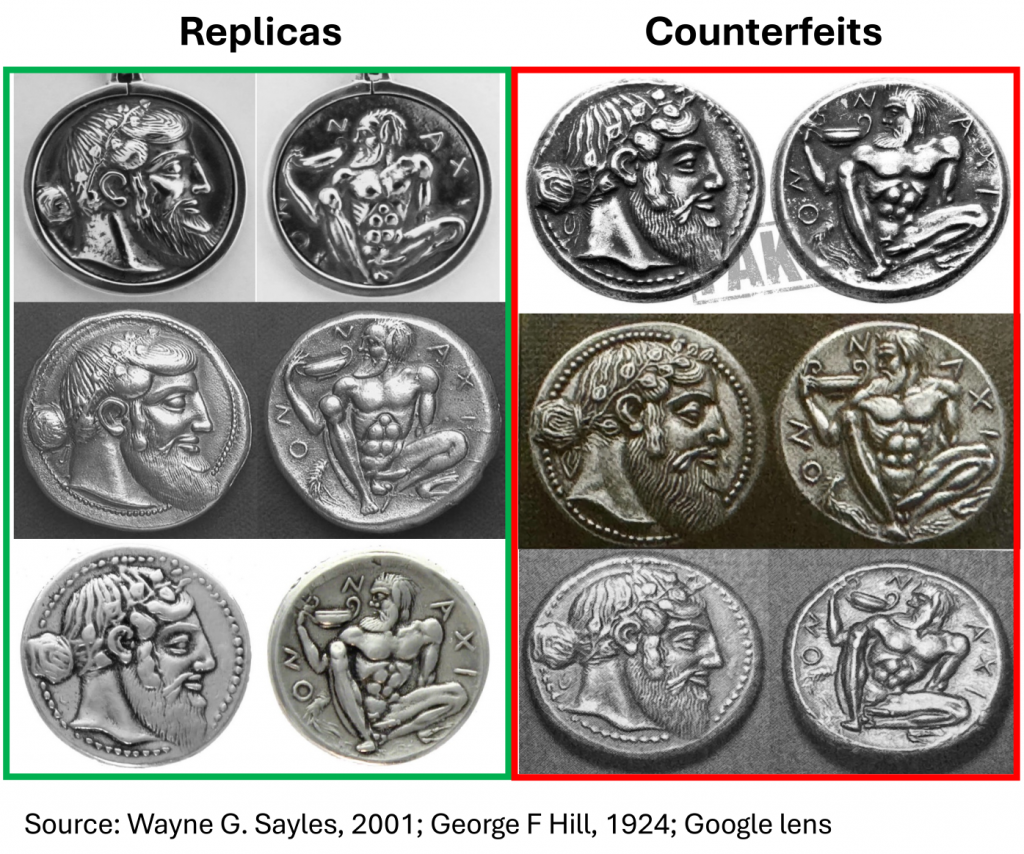

Forgeries go back to the Renaissance but have only really been produced at scale since the time of Wilhelm Becker (1772-1830). There is often some ambiguity in that some purport to be simply replicas, aimed at the mass-market who could not afford to buy an example [Fig. 15]. Most however seek to deceive, as counterfeiters represent their coins as genuine. Others have also produced forgeries since and have protested their innocence23. Like falsified provenance, counterfeit forgeries have precipitated much greater caution.

Naxos Masterpiece?

Holding a Naxos tetradrachm in-hand is a tactile experience. Such opportunities are rare and are to be savoured. Whether at a pre-auction viewing or an appointment-only visit to a museum, there is always a sense of anticipation. With suitable reverence you pick up the Naxos tetradrachm and are immediately struck by how chunky it is. In the tray it is a familiar size, comparable to a modern British pound, Euro or US quarter dollar, or even an ancient Roman denarius or Greek stater. In hand, it is two-to-three times heavier and much thicker. It is a three-dimensional object, with surface contours and elevated edges beyond the punch of the die. As with all struck coins, there are imperfections along its edges, often with cracks, either from the initial strike or subsequent wear. There’s pleasure in simply handling this wonderful object, touching its edges, experiencing its texture, and rotating it between finger and thumb.

Its rarity, beauty and value all contribute to the idea that this 17g piece of silver is indeed a masterpiece. It is its impact, intended or otherwise, that truly defines it as such. Like a pebble being thrown and sending ripples through water, we can only speculate as to the intentions of the Aetna Master and the Naxians. It has certainly left an impression, a testament to an engraver’s virtuosity. Most likely buried during the turmoil that accompanied the city’s demise, it was unearthed centuries later and came to be appreciated by generations of collectors, who continue to pay astronomical prices for this most special of coins. Such a prize has made it the subject of criminal counterfeits, looting, trafficking and false provenance.

For me, it is this dynamic aspect that brings this precious object to life: the stories, personalities, journeys, discoveries and intrigues, and of course high-stakes auctions. They all contribute to give the Naxos coin agency24, and it is this that assures its place as a numismatic Masterpiece.

Dr Tim Wright is an amateur numismatist, based in London and France. He published ‘British Celtic Coins: Art or Imitation’ last year with Spink. His research into the Naxos Masterpiece will be the subject of a lecture at the Royal Numismatic Society on 21st January 2025.

- Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan, 1892: Cecil Graham asks, ‘What is a cynic?’, to which Lord Darlington replies ‘A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing’ ↩︎

- Herbert A. Cahn, Die Münzen der Sizilischen Stadt Naxos, 1944, Verlag Birkhäuser Basel ↩︎

- Callatay, F. de, 2022, La Production Monétaire en Sicilie a l’Epoque Grécque. Une vue d’ensemble quantifiée grace nouveau site web silver, Magistor Optima : Scritti in onore di Maria Caltabiano per i suoi 50 anni di studi numismatici, Citta de Sole Edizioni ↩︎

- CoinsHoards.com ↩︎

- Cahn. pp 115-116 and 152-154 ↩︎

- Cahn, p 42 ↩︎

- Lentini, M. C and Blackman, D. J, 2009, Naxos di Sicilia – L’abitato coloniale e l’arsenale navale – Scavi 2003-2006, Messina, Regione Siciliana Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione ↩︎

- Bradley, R, 2009, Image and Audience: Rethinking Prehistoric Art, Oxford ↩︎

- Finley, M. I, 1979, Ancient Sicily, Revised Edition, London, Chatto & Windus ↩︎

- Thucydides, 1843, History of the Peloponnesian War, translated by T Hobbs, Bohn, 6.3.1 ↩︎

- Suetonius, Divus Augustus, 75; Margaret Ellen Mayo, Collecting Ancient Art: An Historical Perspective in Wealth in the Ancient World, Kimbell Art Museum, 1983, p 28 ↩︎

- Petrarch, Letters on Familiar Matters, Trans. Aldo S Barnardo, NY Italica Press, 2005, p 57 ↩︎

- Roberto Weiss, The Study of Ancient Numismatics During the Renaissance (1313-1517), Numismatic Chronicle, 1966, Volume 8 (1968), p 179 ↩︎

- Alan M Stahl, Numismatics in the Renaissance, Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 69, No. 2, 2008, p 223 ↩︎

- Private correspondence with Jonathan Kagen; see also his Notes on the Study of Greek Coins in the Renaissance, International Symposium, Berlin, 2011, pp 57-59 ↩︎

- Owen Hopkins, The Museum: From its Origins to the 21st Century, 2021, p 47-62 ↩︎

- See, for example, Jeremy Black, The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century, 1992 ↩︎

- See for example, Artnet News, September 11, 2023; Antiques Trade Gazette, 11 September 2023; Coins Weekly, 23 May, 2024 ↩︎

- Court Papers from the Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of New York, Criminal Term (August 2023) ↩︎

- Alvin L Bragg, Manhattan District Attorney, Press Release, February 2, 2023 ↩︎

- Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini, The Medici Conspiracy, 2006 ↩︎

- Arnold-Biucchi, C, 1990, The Randazzo Hoard 1980 and Sicilian Chronology in the Early Fifth Century BC, Numismatic Studies No. 18, The American Numismatic Society, New York ↩︎

- Wayne G Sayles, Classical Deception, 2001 ↩︎

- Alfred Gell, Art and Agency, 1998 ↩︎

By Tim Wright