‘IN THE SPRING-TIME, THE ONLY PRETTY RING-TIME’ (AS YOU LIKE IT, ACT V, SCENE III)

HISTORIC FINGER RINGS AT SPINK, LONDON – APRIL 2025

There’s something a little bit different amongst the lots of the latest Spink Coin sale, in the form of two historic finger-rings. Both are astonishing, recent metal detecting finds which, after working their way through the official Treasure process, have been cleared for sale on the open market. As both a jewellery enthusiast and a lover of a great story, I felt it right to take the time to tell the tales of these two rings. Through the lens of such small but mighty finds, we are able to uncover tales of craftsmanship, empire, trade, love, death, war and friendship. The intensely personal nature of a ring, and its historical (and continuing) use in ritual, has particularly captured my imagination and I’m sure will do the same for many others.

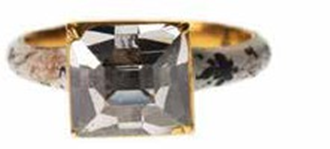

Last October, an email landed in my inbox which contained photographs of a Renaissance era gold ring, with what looked like a diamond set in the centre. It had been found by a metal detectorist back in 2023, in the small village of Fletching in East Sussex. He informed me that, following its submission for consideration as Treasure, the ring had been disclaimed and therefore he, and the landowner, were exploring avenues of sale.

With my interest fully piqued, I delved into researching the piece, which we decided to name The Wealden Ring, after the district in which it was found. Dating to around 1550- 1650, it is similar to other examples recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme, including The Selbourne Ring, found in Hampshire (sold at Noonans in 2023 for £7,440), and another unearthed in Staffordshire, which was acquired by the Stoke Potteries and Art Gallery in 2018.

Similar though they are in design and construction, both of these examples have rock crystal set into the bezel, whereas The Wealden Ring bears a flawless, table-cut diamond. In an age when lab grown specimens bolster their way into the jewellery market by force, a natural stone in such condition makes for staggering viewing. Due to the location of such expertise and trade routes, it likely made its way from an Indian mine, before arriving in France to be cut. Its gold purity of 19 carats is further evidence of this, as it aligns with the so called ‘Touch of Paris’ standard of 19.2 carats used on the continent, compared to England’s 22 – set by an Act of Parliament in 1576.

In a 1700s text by English Puritan divine Hannibal Gamon, titled The Goldsmith’s Storehouse, he writes that the very best diamonds “must be without any faults, both in corners and sides, clean cut without any nastiness, and of a good water crystalline, and shining clear, not yellow, bluish, or blackish or brown, but clear, and clean in all perfection.” I think it is no exaggeration to claim that the central stone of The Wealden Ring fulfils this decree.

“the very best diamonds must be without any faults and of a good water crystalline, and shining clear”

Another of the defining features of this ring are the tongue-shaped cells filled with enamel that surround the diamond. Now a blue-green colour, they were once an opaque white. One of The Wealden Ring’s closest comparable examples is a solitaire diamond ring found amongst the 1912 Cheapside Hoard of 17th Century jewels, now housed in the Museum of London (A14244). The Cheapside specimen also has white enamelling all the way around the band, as well as on the bezel, suggesting that it had been custom made for the wearer, as resizing after such decoration would not have been possible. The cuts of both diamonds are very similar too, with scissor-cut facets being used on both – even clearer when placed side by side.

Another layer of the history of the ring lies in its findspot, near Sheffield Green in Uckfield, close to Sheffield Park. Now a sprawling garden landscaped by Capability Brown and owned by The National Trust, it was once an important ancient estate.

It was mentioned in the Domesday Book, and had been owned by Dukes, Lords and Earls. Even Henry VIII came to Sheffield Park, in August 1538, when he was hosted by Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk. In the surrounding fields and farms, there were other residences that date to the Medieval period. At the time of production, this area was clearly attracting wealthy members of society, many of whom may have recently travelled over from nearby France, leaving us to only imagine who may have owned (and subsequently lost), the very special Wealden Ring.

But whilst the mystery about the Wealden Ring’s story remains hidden, the second of the two rings in the April sale has narrative abounding. Last summer, I completed a formal Treasure valuation for an early 18th century memento mori ring, which had been discovered in Alderbury, Wiltshire back in November 2021, once again by a metal detectorist. A museum was planning to acquire the ring, but the finder had decided to provide a third party market valuation of the ring to ensure that the reward was fair and representative. After sending off my researched valuation, I assumed the ring would eventually be placed in an institution, especially given that there was definite interest. However, just as we approached the consignment deadline for the upcoming sale, I received an email explaining that due to the increased valuation figure, the museum was now no longer able to raise the funds, and the ring had been returned to the finder to sell on the open market. The ring which I had viewed in the back rooms of the British Museum (and didn’t think I’d ever get to handle again!) had found itself in the Spink showroom in London, and back in front of me.

The ring, aside from any exciting provenance, is a beautiful piece of early mourning jewellery. The black enamel that envelopes the decorative floral motif of foliage and thistles is almost wholly intact – incredible for a ring that has been underneath the ground for over three hundred years. It has an oval shaped bezel holding a curious glass insert. With the use of non- invasive ultrasonic cleaning, I was able to clear the majority of soil from underneath the setting, making way for the gold beneath to gleam through. With no monogram or symbol below, I could deduce that it was highly likely a piece of textile or even plaited hair was originally placed behind the glass.

“Thanks to the lack of wear on the ring we are able to trace exactly who this ring was made in remembrance of.”

The inscription on the interior band reads: ‘Wm Hewer. arm. obt 3. Dec 1715. aet 74’, translating to ‘William Hewer, who died on the 3rd December 1715, aged 74.’ Thanks to the lack of wear on the ring, and its inclusion of all necessary specific details, we are able to trace exactly who this ring was made in remembrance of. William Hewer was a notable historic figure, both in his own right, and because of the close company he kept. On both sides of his family he had links to the Admiralty, the government department responsible for the command of the Royal Navy. His father had been their supplier of stationary, whilst evenly more importantly his maternal uncle, Robert Blackborne, had been at the centre of Naval affairs during the Interregnum.

“the kindness you are pleased to express towards me, is such that I want words to express my thankfulness…Living or dying, I shall remain to the end your faithful servant” (Hewer to Pepys)

In 1660, coincidently the same year that he began to write his renowned diary, a certain Samuel Pepys succeeded Blackborne as Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board, making him responsible for organising the Navy Office and completing other administrative duties. Blackborne had introduced the eighteen- year-old William Hewer to Pepys in July of that year, and he appeared to make a good first impression. Pepys wrote in his diary of Hewer (the first of countless mentions) that “Mr Blackburn’s nephew is so obedient, that I am greatly glad of him.” He would soon after become Pepys’s personal clerk, the start of a long and treasured partnership.

The two men worked closely together, both at the Naval Office but also in the domestic realm, with Hewer acting as manservant and confidant. When Pepys moved to the Admiralty in 1673, Hewer came too, before going on to become Chief Clerk the following year. Both were continually successful in their respective roles, and Hewer gained significant wealth from hard work and private trading ventures, greatly helped by his uncle’s involvement with the East India Company. In 1675, Hewer was worth the equivalent of nearly £2 million in today’s money, and owned property on The Strand in London, in Norfolk, and in the then-village of Clapham, where he had bought a ‘country retreat’ in 1688.

By this time, he had become MP for Yarmouth, Isle of Wight, Treasurer of Tangier, and a Special Commissioner of the Navy with particular responsibility for the accounts. The latter kept him particularly busy, as he was appointed to no less than twelve committees. His particular legislative interests lay in the encouragement of ship-building, helping the widows and orphans of London, and rebuilding St Paul’s Cathedral, after it was severely damaged by The Great Fire of London in 1666.

Reading through Samuel Pepys’ diary, as well as personal correspondence, one is truly able to get an idea of how much affection and respect the two men had for one another. Consistently Hewer is portrayed as dependable and trustworthy, as well as diligent and skilled in administrative tasks. When Pepys was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London, on a charge of selling naval secrets to the French in 1679, he wrote that he had received “all the care, kindness, and faithfulness of a son on this occasion, for which God reward [Hewer] if I cannot.”

Both men were imprisoned, following the overthrow of James II in 1689, on suspicion of having Jacobite sympathies and by consequence, treason. However, both were released on bail and never trialled. With Pepys heading into his latter years, he didn’t return to employment in public office. Hewer also turned his attentions away from his political work, and focused on his position as a prominent member of the East India board. At this point, he had funds enough to welcome Samuel Pepys into his Clapham Common home, where Pepys remained until his death in 1703.

“my most approved and most deare friend”

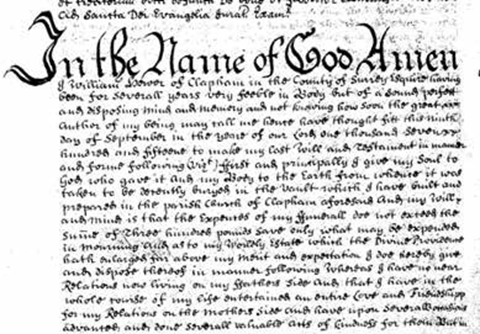

Being his closest companion, Pepys made William Hewer executor of his will, writing: “And I pray my most approved and most deare friend William Hewer of Clapham in the County of Surrey Esquire to take the Trouble as my Executor of Seeing this my Will performed”. He also left him “the said Summe of Five hundred Pounds as a very Small Instance of [his] Respect and most Sensible Esteeme of his more than filiall affection and Tendernesse Expressed towards [his] through all the Occurrences of my Life for Forty Yeares past unto this day”.

William Hewer was the custodian of the entirety of Pepys’ extensive book collection (including the famous diary), for which he had the responsibility of resolving its long term future. Without a wife or any issue, Hewer decided to leave the majority of his own estate to his godson, Hewer Edgeley. This was on the condition that he change his surname, which he did, becoming Hewer Edgeley-Hewer. His own will (pictured above) does not make specific reference to leaving money to make memento mori rings, as is often the case, only for the rather vague “mourning”, but given Edgeley’s already elevated position as heir, and the large size of the ring, I think the assumption that it belonged to him is a fair one.

If you would like to discuss any further details of the two rings, or to explore avenues of consignment, please contact Ella Mackenzie on [email protected]