Spink London, 27th November 2025

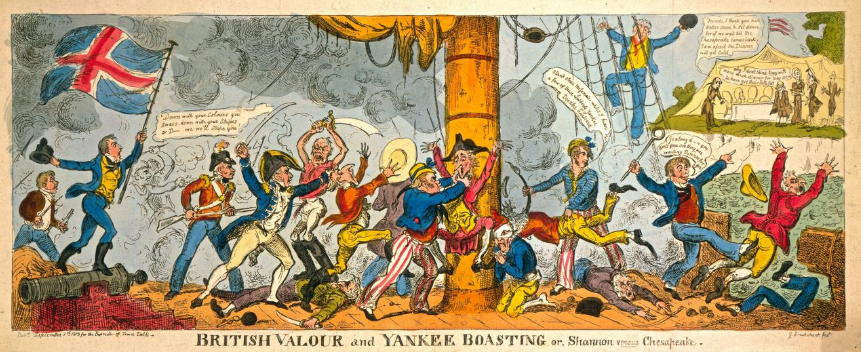

Looking forward to our Autumn and Winter auctions of Orders, Decorations and Medals here at Spink, one of my personal highlights of the November sale will be a Naval General Service Medal with clasp ‘Shannon With Chesapeake’ which was awarded to Boy 1st Class John Robinson. It is one of the rarest (and most desirable) clasps to be found on this campaign medal and it commemorates a famous battle between the Royal Navy and the United States Navy which occurred off the coast of Boston on 1st June 1813. This is the story of that action and, whilst holding this medal in one’s hand, it is not hard to imagine what the recipient thought and felt that famous day.

“Throw no shot away. Aim every one. Keep cool. Work steadily. Fire into her quarters – maindeck to maindeck, quarterdeck to quarterdeck. Don’t try to dismast her. Kill the men and the ship is yours.”

– Captain Philip Bowes Vere Broke to the men of HMS Shannon just before going into action against the U.S.S. Chesapeake: fifteen minutes later, Chesapeake had surrendered, her Captain was mortally wounded, and Broke had won a stunning victory against the American vessel.

Provenance: Glendining’s, June 1938.

16 men of this name are noted upon the Medal Roll, all with single-clasp medals. Some 42 ‘Shannon with Chesapeake’ clasps were issued, this being the only example claimed by a Boy 1st Class.

John Robinson was born circa 1792 and joined the Royal Navy on 7th September 1808 with his first ship noted as HMS Shannon, the 38-gun Leda-class frigate aboard which he was to serve for the next five years and led to his participation in perhaps the most famous single-ship action of the Napoleonic Wars, and certainly of the War of 1812. Shannon, launched in 1806, was commanded by Captain Philip Broke, an officer known for his intense scientific passion for gunnery: he designed his own sights for the maindeck guns and even personally arranged for the addition of some smaller carronades to the usual complement so that his midshipmen could practice with them rather than with the much larger, heavier standard pieces which they would struggle to operate. The entire crew was additionally trained to be proficient in using ‘small arms’ (musket, pistol, cutlass, and boarding pike) and given hypothetical scenarios involving the defence of – or attack on – their ship, seeing how the officers and men would react and work together as a team. It was things such as this, together with Broke’s frequent live-firing exercises against floating targets, that quickly led Shannon to become a crack ship full of confident officers and sailors, Robinson included in their number.

After a few years of service in home waters, in the summer of 1811 Broke and Shannon were ordered to the North America station, arriving at Halifax on 24 September that year. On 5th July 1812 he took command of a small squadron and was given instructions to operate off the east coast of the United States: from then, over the course of the next year until June 1813, Broke and Shannon saw plenty of action in chasing, fighting and capturing a number of smaller American warships, privateers and merchantmen. However, their ultimate test was yet to come.

Patrolling off Boston, Broke was eager to bring the 38-gun U.S.S. Chesapeake (moored in Boston harbour and under the command of Captain James Lawrence) to battle: indeed, Broke was so keen to fight that he famously issued a written ‘challenge’ to Lawrence which (in an abridged form), read:

‘As the Chesapeake appears now ready for sea, I request you will do me the favour to meet the Shannon with her, ship to ship, to try the fortune of our respective flags. The Shannon mounts twenty-four guns upon her broadside and one light boat-gun; 18 pounders upon her maindeck, and 32-pounder carronades upon her quarterdeck and forecastle; and is manned with a complement of 300 men and boys, beside thirty seamen, boys, and passengers, who were taken out of recaptured vessels lately. I entreat you, sir, not to imagine that I am urged by mere personal vanity to the wish of meeting the Chesapeake, or that I depend only upon your personal ambition for your acceding to this invitation. We have both noble motives. You will feel it as a compliment if I say that the result of our meeting may be the most grateful service I can render to my country; and I doubt not that you, equally confident of success, will feel convinced that it is only by repeated triumphs in even combats that your little navy can now hope to console your country for the loss of that trade it can no longer protect. Favour me with a speedy reply. We are short of provisions and water, and cannot stay long here.

Though Lawrence did not actually receive the challenge, by coincidence he took Chesapeake to sea on the very morning that the note was being delivered to him by a boat manned by a discharged American prisoner: at 5.30 p.m. on 1st June 1813 the stage was set. Both sides were equally confident of victory, with ships of almost identical armament and tonnage: Chesapeake‘s crew was greater by almost 50 men, but Shannon‘s crew were better-trained and led and it was this fact which would soon prove decisive.

As Chesapeake bore down on Shannon, the British sailors observed that their opponent was flying no fewer than three American ensigns and a further flag at the foremast displaying the words ‘Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights’; on seeing this, one of Shannon‘s crew approached Broke and said: “Mayn’t we have three ensigns, sir, like she has?” Broke responded, with exceptional sang-froid: “No – we’ve always been an unassuming ship.”

Shannon and Chesapeake opened fire just before 6pm at a range of only 115ft, with Shannon‘s aftmost starboard 18-pounder hitting Chesapeake‘s forward gunport; the American vessel was moving faster than Broke’s ship, and as she ranged along Shannon‘s side the British gunners inflicted enormous destruction due to their precise and methodical gunnery. The Americans returned a brisk fire, but failed to do as much damage with the maindeck guns as Chesapeake was heeling over; much of her heavy shot struck the water rather than hitting Shannon. Captain Lawrence now saw that, as he was moving faster than Broke, he needed to slow down and ordered a brief turn into the wind to reduce speed – a dangerous manoeuvre as this would present Chesapeake‘s vulnerable stern to Shannon‘s broadside. Then things started to very quickly go wrong for Lawrence.

As this move was being carried out, another deadly accurate broadside from Shannon caused havoc: Chesapeake‘s quarterdeck was swept clear of officers and men, both helmsmen being killed at the wheel and indeed the wheel itself being shattered by fire from a 9-pounder which Broke had specifically installed on his quarterdeck for that very purpose. At almost the same moment as the American ship lost the ability to steer, her fore-topsail halyard was shot away and the yard dropped: she now turned even further into the wind and stopped, before making sternway towards Shannon, all the while still presenting her vulnerable, unarmed stern and being pummelled by British cannon fire. Chesapeake‘s port stern quarter hit Shannon‘s starboard side and became hooked on one of her anchor flukes: she was now trapped, at an angle where few of the American guns could bear but Broke’s men could sweep the length of Chesapeake with an horrific raking fire. An open cask of musket cartridges just behind Chesapeake‘s mizzen mast exploded and when the smoke cleared Broke, who had been keeping an intense and ever-watchful eye on the ebb and flow of the battle, decided it was time to make the decisive strike and board his battered opponent. Lawrence, too, ordered his men to board at the same time, but the bugler he had detailed to sound the appropriate signal was nowhere to be found and his cry went almost unheeded. By now, the American captain was the only officer on the upper deck – two of his Lieutenants had been wounded and carried below – and as the senior unwounded Lieutenant, William Cox, appeared from the lower deck he found Lawrence struggling to stand upright: he had been hit by a British musket ball and the wound was mortal. It is believed that, as Cox helped Lawrence below to the surgeon, he cried out: “Tell the men to fire faster! Don’t give up the ship!”

In contrast to the loss of leadership and confusion on Chesapeake, Broke and the men of Shannon were superbly organised and ready to go: the British captain led 20 men across onto the American frigate’s quarterdeck in the face of some resistance (both Broke’s purser and clerk being hit and killed by musket fire), but swiftly despatched their opponents and then realised there were no American officers left in that part of the ship. Neither were any Americans to be seen on Chesapeake‘s maindeck, either being killed by Shannon‘s gunfire or having deserted their posts to take refuge below the waterline. However, two of Lawrence’s lieutenants now returned from below and rallied a number of sailors who launched a counter-attack: this drove Broke and his men back towards the quarterdeck but British reinforcements arrived and, as both American officers fell with cutlass wounds (one of them mortal), their valiant attempt to reclaim their ship ended in failure and resistance around Chesapeake‘s stern and maindeck finally collapsed with many sailors again fleeing below, leading Lieutenant Cox to exclaim: “You damned cowardly sons of bitches! What are you jumping below for!?”

While all this was going on, battle continued between the fighting-tops of the two ships with the men stationed in them sniping at one-another and upon those on the deck below: astonishingly, Midshipman William Smith (in command at Shannon‘s fore-top) stormed Chesapeake‘s fore-top via the yard-arm and killed all their opposite number. However, at this moment the wind picked up and the two vessels broke apart, with Chesapeake being blown around Shannon‘s bows: this left the British, with Broke at their head and some 50 in number, stranded aboard the enemy vessel. Fortunately, resistance had mostly collapsed and Broke was confident victory was his: he personally led a charge against the last element of the visible American crew on the forecastle. Whilst in hand-to-hand combat, he was identified and set upon by three sailors: Broke killed one, but the second hit him with the butt of a musket and the third cut him across the head with a sword, flinging him to the deck. Just as the American sailor went in for the kill, he was in turn bayoneted by a Royal Marine and, at the sight of their gallant captain going down, Shannon‘s crew launched themselves in a final, frenzied melee which captured this last bastion of American defence, killing all those in their way. The time had now come to hoist British colours over Chesapeake‘s ‘Stars and Stripes’, an act symbolically undertaken by Broke’s First Lieutenant, George Watt – tragically however, as he did so one of the gun crews aboard Shannon mistook this in the smoke for the re-raising of the American flag as an act of defiance: the gun was fired and Watt fell dead, hit by British grapeshot in the moment of victory.

According to Shannon‘s log, the short but bloody battle had lasted a mere 10 minutes; Lieutenant Provo Wallis’s watch said 11 minutes, and Broke claimed 15 minutes in his official despatch. Whatever the case, it had been a remarkable and triumphant victory for the Royal Navy at a time when the ‘senior service’ was losing far too many single-ship actions against the fledgling U.S. Navy. However, the ‘Butcher’s Bill’ was correspondingly high – especially considering the time elapsed from opening shots to final surrender: Shannon had lost 23 men killed and 56 wounded; Chesapeake‘s casualty list included at least 48 killed (including four lieutenants; the Master; and most of her officers) and 99 wounded – including Captain Lawrence, mortally. With Broke also dangerously wounded, command of Shannon became the responsibility of Lieutenant Wallis (who, incidentally and impressively, was the last survivor of the battle when he died in 1892 as an Admiral of the Fleet just a few months short of his 101st birthday) and Lieutenant Falkiner and his prize crew took command of Chesapeake; both ships arrived at Halifax on 6 June to a rapturous welcome which included victory dinners, balls, patriotic songs, and general celebrations. Robinson must have felt a great deal of pride to be so feted as one of Shannon‘s gallant crew.

After repairs and a brief cruise, Shannon departed for England on 4 October, arriving at Portsmouth on 2 November: Lieutenants Wallis and Falkiner were promoted Commander and Broke was showered with gifts and honours including a Baronetcy (‘of Broke Hall’), the Freedom of the City of London, a Naval Gold Medal, and a 100-guinea sword – though due to his dangerous head wound he never again saw active service. Robinson had been raised from Boy 1st Class to Landsman (29th September 1813) and departed Shannon in November of that year to join the 22-gun sixth-rate HMS Comus; in May 1814 he removed to the 36-gun frigate HMS Granicus and was finally discharged from the Royal Navy on 26th October 1815.

As a point of interest, Shannon remained afloat until 1859, when she was finally broken up. Two of her sister ships, HMS Unicorn and HMS Trincomalee, still exist to this day as museum ships in Dundee and Hartlepool respectively. Chesapeake entered the Royal Navy as HMS Chesapeake but was sold out of service in 1819. Large parts of her timbers where then used to build a watermill at Wickham, Hampshire, which also still exists and is called the ‘Chesapeake Mill’. Somewhat bizarrely, as a watermill Chesapeake is the most originally-preserved of the original six frigates of the United States Navy!

John Robinson’s Naval General Service Medal will be offered in our auction of Orders, Decorations and Medals at Spink London on 27th November 2025, and carries an estimate of £8,000 – £12,000. For further information please contact Robert Wilde-Evans, [email protected].