This is the tale of the making of a groat in Cork. It is one of three Irish coins known from the second reign of Henry VI, all of which are Cork groats. The first specimen to be identified was offered for sale in London in 2016 (1); a second, from the same obverse die, was identified subsequently in the collection of the National Museum of Ireland. The third specimen, discussed here, is from different dies to the others, with a unique feature that bears contemporary witness, perhaps more eloquently than any other object, to one of the most convulsive events of medieval Irish history. I have had the privilege to study it in collaboration with Gregory Edmund, coin specialist at Spink, to whom I am also grateful for highlighting the apt Latin phrase with which this article concludes.

In the following, primary sources in English, in particular Warkworth’s Chronicle and excerpts from letters of the Irish Parliament and Richard III, are quoted in the original Middle English. Primary source material in Hiberno-French from the Statute Rolls of the Irish Parliament is quoted in translation. Quotations from the Irish Annála (Ríoghachta Éireann, Connacht, Uladh, Loch Cé, some contemporary but others collated later from primary material) are translated from Irish.

1. How it all began

On 1st May 1169, Maurice Fitz Gerald, the son of the constable of Pembroke castle, stepped ashore in Ireland at Bannow Bay in County Wexford. He had sailed from Milford Haven as part of the advance guard of Cambro-Norman adventurers who came at the invitation of Diarmat Mac Murchada, to support him in his contention for the high kingship of Ireland; (2) one of the “pirates whom he [Diarmat] brought with him from the east, to spoil Éirinn”, in the opinion of the Annála Loch Cé. (3) Maurice’s two eldest sons, Thomas and Gerald, were the founders of what would become the great Anglo-Irish earldoms of Desmond (Deas Mumhan/South Munster) and Kildare respectively.

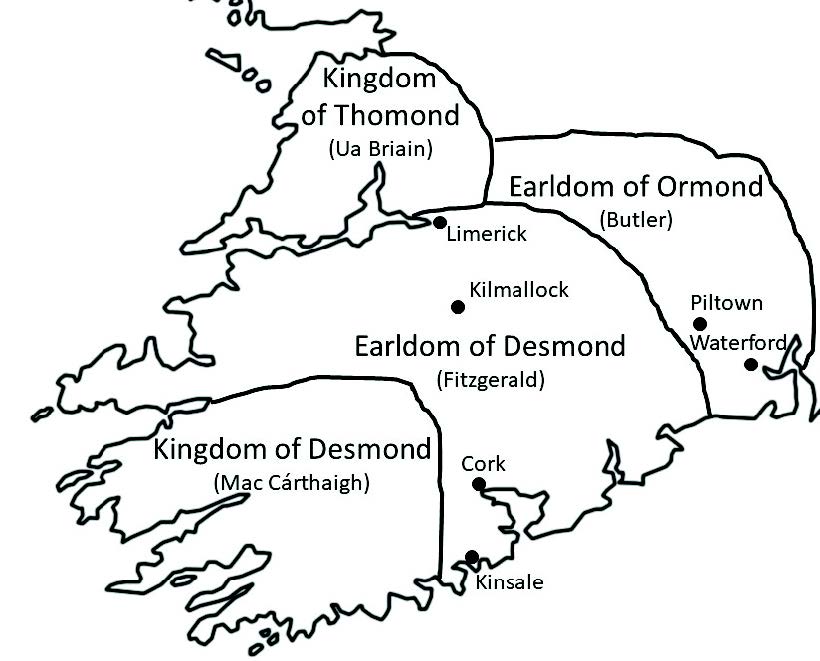

The earldom of Desmond was established around a landholding that Thomas received from King John in 1199 in the vicinity of Kilfinnane (4), less than five miles from Kilmallock, in the south of what is now County Limerick. It was the most western, and gaelicised, of the Anglo-Irish earldoms, and developed customs and practices that straddled Gaelic and Anglo-Norman traditions. Its power was sustained by a large standing army supported by the Gaelic tax of coinnmheadh, or ‘coyne and livery’, the levying of free board and billet for large bodies of troops on the local population. The third earl Gearóid (d. 1398) was a noted poet in Irish and French. By 1460, the earldom spanned a region of Munster indicated approximately by Figure 1, comprising parts of the modern counties of Limerick, Cork and Kerry.

The earldom was bordered to the south west by the Gaelic kingdom of Desmond of the Mac Cárthaigh, who had checked the initial Fitzgerald expansion decisively at the battle of Callan in 1261 (5); to the north across the Shannon by the Gaelic kingdom of Thomond (tuadh Mumhan/north Munster) of the Ua Briain, the descendants of Brian Bóramha, the victor of Clontarf; and to the east by the earldom of Ormond (oirr Mumhan/east Munster) of the Butlers, the bitter hereditary rivals of the Fitzgeralds, who alone amongst the major Anglo-Irish families took the Lancastrian side in the War of the Roses. As the power and influence of the Yorkist Desmonds grew, the Ormonds shared in the Lancastrian disaster of the battle of Towton in March 1461. Their fifth earl James was attainted with treason and beheaded in its immediate aftermath, and the family was stripped of their land until 1470.

2. The “Most Excellent of his Tribe”

In 1462, Thomas Fitzgerald succeeded his father as the seventh earl of Desmond, and in August that year, was made constable of Limerick castle for life. (6) The same summer John Butler, the younger brother of James, landed in force in Waterford in the hope of re-gaining the Ormond earldom; he and his forces were met at Piltown (Baile an Phuil/Town of the Blood) by the Desmonds under Fitzgerald, where Desmond and York prevailed, the river ran red, and Butler was “himself scomfuted put to flight et to rebuke.” (7)

Rewarded for his loyalty by Edward IV, in April 1463 Fitzgerald reached the height of his power when he was appointed Lieutenant (Lord) Deputy of Ireland, (8) the fourth and last of his house to hold the office, replacing William Sherwood, the English-born bishop of Meath. (9) Because of his western upbringing, he had an unusual (for a Lieutenant Deputy) appreciation of, and sympathy for, the concerns of regional Ireland, and he broke with the Palecentric, eastern-facing focus of his predecessors in office. A core stimulatory component of his policy was the great decentralisation of mint activity he instituted from 1463-5, extending the right to coin from Dublin to Waterford, Limerick, Galway, Trim and Drogheda; with Cork possibly following, in a demi-monde of tolerance, during his lifetime. While it was in his direct personal interests to pursue this policy – given his positions of feudal authority over three of the regional mint locations – it was also undoubtedly in those of the neglected regional populations he represented.

In 1465, he mitigated draconian parliamentary restrictions on the expression of Gaelic identity within the Pale by legalising, and promoting, trade between the Gaelic and Anglo-Irish communities in Munster (10). And he brought forward a truly visionary plan to establish an Irish university in Drogheda (11), anticipating, at least in design, the foundation of Trinity College Dublin by over a century. This year marked his apotheosis. He suffered a serious military defeat in Offaly in 1466; (12) and worse, in a major political blunder, he imposed coinnmheadh on the people of the Pale, arousing resentment and suspicion in the political heart of the Lordship.

It would be wrong to deify Fitzgerald, the battle-hardened, imperfect, political son of a brutal age and a warlike house. However, it is clear that he possessed unique, unifying qualities of leadership, genuine cross-community respect and support, and a humanist Renaissance spirit. From the Gaelic perspective of the Annála Ríoghachta Éireann, he was “the most excellent of his tribe [the Anglo-Irish] in Ireland in his time…for his hospitality and chivalry, his charity and humanity…his bounteousness in bestowing jewels…on the…[Gaelic] poets” (13); while from the Annála Uladh “the learned relate that there was not ever in Ireland a Foreign youth who was better than he” (14). The Anglo-Irish parliament and council deemed him “right faithfull et true” in a letter to the king, and lauded him for his “Reule manhode wisdom & gouernaunce” in suppressing rebellion “without eny hurt off eny person” (15). Under the guidance of his enlightened policies, the first tentative steps were taken down a long road that is still being trodden by the communities of Ireland today; the road to a shared future of respectful co-existence, founded on economic and cultural exchange to mutual benefit, within a society supportive of learning and the arts. With counterfactual naivety, one might conceive of an alternative Ireland, where the brave initiatives of Fitzgerald’s short tenure were allowed to mature and develop under his unifying leadership; another Ireland in which the road yet to be travelled was shorter, and not so drenched with blood. But it was not to be. The terse final entry of the Annála Ríoghachta Éireann for 1467 reads: “An English Justiciary came in Ireland, and Thomas was replaced, and the ruin of Ireland came thereafter.” (16)

3. The English Justiciary

John Tiptoft, the earl of Worcester, was born to a prominent Lancastrian family in 1427, and studied theology at University College Oxford. His first wife was a Yorkist, and he shifted his allegiance as the power of Richard of York waxed through the 1450s. He was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1456, but in 1457 he departed for Italy, remaining there until 1461, perhaps in a deliberate attempt to avoid the great instabilities of those years of the War of the Roses. While there, he devoted himself piously to religion, and to the enthusiastic study of the merciless tenets of ancient Roman law at the University of Padua. On his return to England he was appointed Constable of the Tower and Lord High Constable by Edward IV, the latter position giving him the scope to demonstrate a notable penchant for torture and summary execution. He was made Lord Chancellor in January 1464, and on the 26th of that month he appointed Sherwood as Lord Chancellor of Ireland. However, the day before in Ireland, Fitzgerald had appointed his kinsman the earl of Kildare (who, confusingly, was also named Thomas Fitzgerald), to the same post, in an appointment confirmed by the Irish parliament. The result was a dangerous dispute, which had to be resolved by Desmond and Sherwood appearing before the king (17). Edward retained Desmond as his Lord Deputy, and made him lord of the manor of Trim (18) (where the mint would open soon after, perhaps not coincidentally). It is reasonable to infer that the affair created (or deepened) ill will between Fitzgerald on the one hand, and Tiptoft and Sherwood on the other, the latter emerging as the leader of the small faction in Ireland opposed to Fitzgerald. Tiptoft was re-appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1465, though due to concerns elsewhere was unable to take up the post, so Fitzgerald was retained until late in 1467, when Tiptoft arrived in Ireland.

He soon summoned a parliament in Drogheda in the north of the Pale, which Fitzgerald attended, by Desmond accounts with letters guaranteeing safe passage. There Tiptoft attainted both Thomases with treason, for “alliance, fosterage and alterage [altradh/nursing] with the Irish enemies of the king”. (19) Kildare managed to escape, to plead his case successfully before Edward IV; but Desmond was seized from a friary (20), in violation of sanctuary, by Tiptoft’s men on 15th February. They dragged him, protesting his loyalty and innocence, to the scaffold, and struck off his head. Then they struck off the heads of two of his sons, the older of whom was thirteen. (21) As he followed his father and brother to the block, the younger requested that care be taken of an abscess, from which he suffered on his neck, in his decapitation. (22)

4. The Doom of Desmond, and the Judgement on the Justiciary

“Great and uncountable was the loss in that place, though the numbers slain were few”, (23) wrote the Four Masters in their assessment, from a Gaelic perspective, of the Battle of Kinsale in 1601; but they could as well have written it, from the perspective of both communities, of the site of Fitzgerald’s execution. “The hearts of the men of Ireland and of their wives were broken”, was the lament of the Annála Connacht. The event would shake and fracture the Lordship to its core, and weave a weft of woe with few parallels through the fabric of Ireland’s history, a scarlet strand that threaded the fates of generations. Despite the restoration of Thomas’s land and titles to his son James by Edward in August 1468, it wrought the slow, creeping, inexorable doom of the House of Desmond. The breach with the crown, brought about by its representative, was too great to be mended; for in the words of Richard III, Fitzgerald had been “extorciously slayne and murdred by colour of the lawes…ayenst alle manhode, reason and good con-science.” (24) That this befell the Anglo-Irish leader most sympathetic to, and respectful of, the Gaelic community, and, nominally at least, for that very reason (25), only compounded the disaster. For decades, Fitzgerald’s Desmond successors would assert the right not to be summoned to parliament, or to be required to enter walled towns, granted them by Edward IV in token of atonement; and they rose in outright rebellion repeatedly. They aligned themselves ever more closely to the Gael, and were to initiate the strategy of continental agitation for intervention in support of their cause, which, for the Gael, was to be brought to calamitous fruition at Kinsale. The sectarianism which followed the English Reformation heightened tensions with the crown to an unsustainable degree, and the House of Desmond fell in final ruin in 1583, with the fugitive death of Gerald, the fifteenth and last earl, whose head would adorn London Bridge (26) after one rebellion too many. There followed the Plantation of Munster, by Protestant colonists from England and Wales on seized Desmond land in 1586, priming a sectarian powder keg that would explode in an orgy of violence in the War of the Three Kingdoms.

This mischief accomplished, Tiptoft devalued the Irish coinage by half, and caused it to be marked with an unmistakeable new design, the reverse radiant sun of his “Doubles”. The outcome was economic chaos and great hardship for the Pale, by which, quoth the parliament in 1470, the “people are so greatly impoverished… that many of [them]…are like to perish from want”. (27) Meanwhile, in the immediate Desmond response to the execution, Gerrot Fitzgerald, younger brother of Thomas, “of his haughty will and malice prepense” mustered the Desmond host and marched across Ireland to rampage through Meath and Kildare, where they “with banner displayed in manner of war…over[ran], burned, wasted and destroyed the King’s faithful subjects inhabiting therein”. (28) Tiptoft appears to have withdrawn to Dublin in the face of this onslaught, forsaking the Pale to the swords and fire of the raging zenith of Desmond might. It is probable that the Meath estates of William Sherwood suffered particular devastation in the attack. Following their campaign, they withdrew to Munster in smouldering rebellion, and were not to be even partially reconciled to the crown until 1476, when James was appointed constable of Limerick castle by Edward (29) in a sign of rapprochement. The office had been left unfilled since Thomas’s death, the castle manifestly outside of Edward’s control.

Tiptoft was later recalled to England, and in 1470 Edward made him the judge of captured soldiers of the forces of the duke of Clarence and the earl of Warwick. This gave him a last stage on which to demonstrate his indifference to human life, which he now refined to a grotesque extremity of barbarism unprecedented in the England of his day: “and so XX. Persones of gentylmen and yeomenne were hangede, drawne, and quartered, and hedede; and after that thei hanged uppe by the leggys, and a stake made scharpe at bothe endes, whereof one ende was putt in att bottokys, and the other ende ther heddes were putt uppe one”. (30) But he was unable to flee with Edward IV on Henry VI’s readeption, and, “juged be suche lawe as he dyde to other menne”, (31) he went to his own dismemberment by the Lancastrians on Tower Hill, for the second time, on 16th October 1470. He had survived the first occasion because of the multitudinous crowd which assembled to witness his destruction, causing it to be postponed. On the way, he was challenged by an Italian priest for his murder of Fitzgerald’s children; his response was that he had done it for the state. (32) Then, in the thunderous phrase of the Annála Ríoghachta Éireann, “the earl of Warwick and the duke of Clarence made quarters of the wreck of the curses of the men of Ireland.” (33) Pointedly, none of the Irish Annála ever mention his name. And so he died, “gretely behatede emonge the peple” (34) of England and Ireland alike.

5. The coins that bear witness

“Almost nothing remains of the written records of the Desmonds, their earldom or their lordship” (36) due to their extinction in the 16th century, as noted by a leading scholar of the House. Almost nothing –apart from their coins. The coins bear few words; but as the only available medium of mass written communication in a society before the printing press, the words that they bear speak clearly indeed. The Desmond mints continued their activities through much of the 1470s, despite repeated commands by the Irish parliament to stop (the parliament itself recognised the futility of doing so: “the King’s writs do not run and are not obeyed amongst them” (37). It is likely that they persisted in activity, at least sporadically, until the thaw in relations with the crown in 1476, and the final parliamentary condemnation of their outputs in 1477.

The Limerick mint was the more prolific, operating from the centre of Desmond power and wealth in the castle. The precise dating of many of its issues is conjectural; but what is not is a very clear change in the representation of Edward IV, and his relationship to the earldom, that was published by the mint at some point from 1465-1477. This is illustrated by the coins of Figure 4. The obvious interpretation is that this change was caused by Fitzgerald’s execution, and documents how attitudes within the earldom responded to it; and that the illustrated coins were issued either side of 15th February 1468.

And so to Cork, on an October day in 1470, far beyond the Pale and the coloured law of the fractured Lordship, in a wounded earldom that has fought and won the only battle of the War of the Roses on Irish soil for the Yorkist cause, only to see their greatest son consumed by a monster in the service of the crown; while in London, Henry VI of Lancaster sits again on the throne of England. To a unique moneyer preparing his tools in an illicit mint: seven punches, his hammer, and a die in the name of EDWARDVS, from which, in a vestige of allegiance, he has been issuing groats independently for months, in defiance of his enemy’s devaluation and design. One of the coins from his Edward die will survive, and, centuries hence, find its way to the collection of the National Museum of Ireland. But the task on which he is engaged as we join him is of a different sort; and he is the only moneyer of his time who will perform it. He knows that by it his head may be forfeit, should he ever be taken by Yorkist authority. His name is John Fannyng; and his staff in Cork and nearby towns are John Crone, Patrick Martell, William Synnot, Morytagh O’Hanrighan and Nicholas Rewy. What he does not yet know is that within two years, they will all be outlawed and attainted with treason (38), for what he is about to do.

A few blows with his blank punch, and the king’s name starts to disappear. He positions his next punch carefully over Edward’s W. Perhaps he thinks of his lost earl Thomas as the hammer falls: H. Perhaps he thinks of Fitzgerald’s murdered children: E. Perhaps he thinks of the ruin of Desmond, and of Ireland: N. Just perhaps, he is a pragmatic artisan, and thinks nothing of such things but only of his work in hand: R. Whatever he is thinking, the next blow falls so heavily that it breaks the punch: I. And perhaps, as he readies to strike the final letter, he thinks of Tiptoft, and of another old Roman practice that might be learned of in Padua: Damnatio memoriae, C.

Cork groat, HENRIC’ over EDWARDVS; unique. [Image courtesy Spink.]

Footnotes

1 Dix Noonan Webb, 21st March 2016, Lot 890.

2 Martin 1993.

3 Hennessey 1871; entry for 1170.

4 McCormack 2005,28

5 McCormack, 2005, 30.

6 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1461-7 196.

7 Parliament Roll 3 Edward IV, 68; Berry 1914, 182.

8 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1461-7 270.

9 Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005.

10 Parliament Roll 3 Edward IV, 44; Berry 1914, 139.

11 Parliament Rolls, Berry 1914, 299-303.

12 Quinn 1993, 600.

13 O’Donovan, 1851. Entry for 1468.

14 Mac Carthy, 1895. Entry for 1468.

15 Parliament Rolls, Berry 1914, 181-187.

16 O’Donovan, 1851.

17 McCormack 2005, 60.

18 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1461-7 340.

19 Parliament Roll 7 & 8 Edward IV, 17; Berry 1914, 465.

20 Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005.

21 Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005.

22 Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts at Lambeth, vol. 5, The Book of Howth, pp. 186-187; quoted in Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005.

23 O’Donovan 1851, entry for 1601.

24 J. Gairdner, ed., Letters and Papers Illustrative of the Reigns of Richard III and Henry VII, 2 vols., vol. 1, London 1861, p 68. Quoted in Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005.

25 The Desmond belief, explored in detail in Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005, was that the true reason was the unholy revenge of a spiteful queen.

26 McCormack 2005, 17.

27 Parliament Roll 10 Edward IV, 4; Berry 1914, 651-3.

28 Parliament Roll 7 & 8 Edward IV, 69; Berry 1914, 617.

29 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1467-76 595.

30 Halliwell 1839, 8.

31 Halliwell 1839, 13.

32 A. Mai and A. Bartoli, eds., Vite di Uomini Illustri del Secolo XV scritte da Vespasiano da Bisticci, Florence 1859, p. 404. Quoted, with translation, by Ashdown-Hill & Carson, 2005.

33 O’Donovan 1851. Entry for 1470. Derived from the corresponding entry in the Annála Connacht, which

predates it.

34 Halliwell 1839, 8.

35 Translation of “ille trux carnifex et hominum decollator horridus”, the contemporary opinion of a partisan Yorkist chronicler on the same side as Tiptoft, quoted with citation in Halliwell 1839, 63.

36 McCormack 2005, 20.

37 Parliament Roll 15 & 16 Edward IV, 55; Morrissey 1939, 376-381.

38 Parliament Roll 12 & 13 Edward IV, 10; Morrissey 1939, 17-19

References

Ashdown-Hill, J., & Carson, A. (2005). The Execution of the Earl of Desmond. The Ricardian Vol. 15.

Berry, H. F. (1914). Statute Rolls of the Parliament of Ireland: First to the Twelfth Years of the Reign of King Edward the Fourth . Dublin.

Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward IV, 1461−1467. (1897). London.

Calendar of the Patent Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward IV, Henry VI, 1467−1477. (1897). London.

Halliwell, J. O. (1839). A Chronicle of the first Thirteen Years of the Reign of Edward IV, by John Warkworth. London.

Hennessy, W. M. (1871). Annála Loch Cé, Vol. 1. Dublin.

Mac Carthy, B. (1895). Annála Uladh [Annals of Ulster] AD 1379–1541. Dublin.

Martin Freeman, A. (1970). Annála Connacht. Dublin.

Martin, F. X. (1993). “Allies and an Overlord”, in A New History of Ireland, Vol. II (A. Cosgrove, editor). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McCormack, A. M. (2005). The Earldom of Desmond 1463-1583. The Decline and Crisis of a Feudal Lordship. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

Morrissey, J. F. (1939). Statute Rolls of the Parliament of Ireland, 12th and 13th to the 21st and 22nd Years of the Reign of Edward IV. Dublin.

O’Donovan, J. (1851). Annála Ríoghachta Éireann [Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland]. Dublin.

Quinn, D. B. (1993). “Aristocratic autonomy 1460-94” in A New History of Ireland Vol II, Medieval Ireland 1169-1534 (A. Cosgrove, editor). Oxford: Oxford University Press.