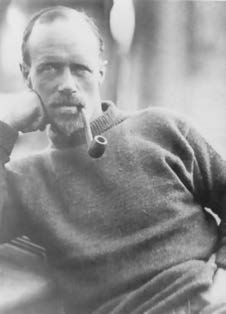

Marcus Budgen

200 YEARS OF POLAR EXPLORATION

In November 2019 Spink unveiled the most important exhibition dedicated to Polar exploration ever staged, finally bringing Frank Wild out of the shadows to join Scott, Shackleton and Mawson among the greats of the Heroic Age. It featured clothing, equipment, medals and other memorabilia from Scott, Shackleton and all of the leading explorers from the Franklin expedition to the modern day, including Henry Worsley, who tragically died during his final Antarctic expedition in 2016.

The exhibition, charted the history, experiences, sacrifices and brotherhood of these seminal polar expeditions – from the search for the Northwest Passage during the 19th century to Shackleton’s death in 1922 – bringing to life the characters, their thoughts and feelings. It was staged to benefit The Endeavour Fund – a charity championed by Henry Worsley and his family – which supports the ambitions of wounded, injured and sick service personnel and veterans wishing to use sport and adventurous challenge as part of their recovery and onward rehabilitation.

The unprecedented display was created in partnership with collectors as well as the Scott Polar Research Institute, and marked the centenary of the end of the Heroic Age of Exploration, as Shackleton prepared for his final expedition. It included many iconic pieces that had never been seen together before and also gave centre stage to the largely unsung heroes of the great Antarctic expeditions of the early 20th century.

Little mentioned outside polar exploration circles is Frank Wild, the Yorkshire-born seaman who took part in five expeditions between 1901 and 1922, becoming Shackleton’s second-incommand in both the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-16 and the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition of 1921-22, which proved fatal to its leader when Shackleton died of a heart attack, aged just 47. Wild took over the expedition, leading it to its completion along the Antarctic coast.

Any one of these individuals could easily command a dedicated exhibition in their own right, so to be able to present dozens of them together as a kind of polar fellowship in this way is truly extraordinary. There’s no telling when, if ever, this will happen again.

Marcus Budgen, Head of the Medal Department, Spink.

Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott were the giants of Polar exploration in the period, with Lawrence Oates, Edward Wilson and Edward Evans among those adding to the legend.

Today, however, Wild is considered one of only four men – Scott, Shackleton and Sir Douglas Mawson being the others – who define the Heroic Age of Polar exploration.

The Polar Record for January 1940 in reporting Wild’s death the previous year recorded: “Frank Wild’s death must have been the first thought of Antarctic men meeting each other this winter. Apart from the leaders, no other Antarctic figure has so impressed himself on so many of the rank and file as Wild; for he had been a member of no less than five great expeditions, second in command on the later ones, but on all, whether in high position or not, acting as the guide and instructor to those new to Antarctic work. In many ways, Frank Wild was the greatest of them all.”

It was in the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1916 that Wild took charge of the 21 men left on the remote and desolate Elephant Island when Shackleton and five others set off on their epic 800-mile rescue mission aboard a lifeboat, and it was Wild who kept the men alive until the rescue party arrived.

Wild is the only man to have taken part in all four of the major Antarctic expeditions of the period, interspersing his adventures with service as a Temporary Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve during the First World War, becoming the Royal Navy’s transport officer at Archangel after taking a Russian language course.

Wild’s later life in Africa was, in many ways, as challenging as his polar exploits. From farming to work on the railroads and even a stint as a hotel barman, disaster struck all too often as his health deteriorated, and it was only towards the end of his life that he finally found peace with his second wife as a store-keeper in mining territory in South Africa.

His diabetes and pneumonia finally caught up with him in August 1939 and he died at the age of 66.

While his name may not be as familiar as Scott and Shackleton, Evans or even Oates among the wider public, he has long been a hero and legend to polar aficionados.

Awarded the CBE in 1920, he became a Freeman of the City of London in 1923, having won the Royal Geographical Society’s Back Award in 1916 and going on to win its Patron Medal in 1924.

Ultimate recognition only came in 2011, when Wild’s ashes were re-interred to the right hand side of Shackleton’s grave in South Georgia, marked by a granite block carved with the words Shackleton’s right-hand man. The burial coincided with the issue of a set of commemorative stamps by South Georgia and the South Sandwich islands honouring Wild and his fellow Antarctic pioneers.

In 2016 a statue of Wild was unveiled in his birthplace, Skelton-in-Cleveland.

As well as charting the challenges and adventures of explorers from the 19th century through the Heroic Age, the exhibition showed how the indomitable spirit of these pioneers remains today in the likes of Henry Worsley, a Lieutenant-Colonel in The Rifles, who led a successful Antarctic centenary expedition of Shackleton’s Nimrod party in 2008, before becoming the first person to have successfully undertaken the routes taken by Shackleton, Scott and Amundsen in another centenary expedition to the South Pole in 2011. Worsley’s final attempt came in 2015, when he made another Antarctic attempt in the steps of Shackleton before falling ill with peritonitis, to which he succumbed in January 2016.

This was a unique non-selling exhibition for Spink, who decided to put commercial interests aside and take advantage of this unique opportunity to create a landmark exhibition to celebrate these extraordinary pioneers.

For scientific leadership, give me Scott; for swift and efficient travel, Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems to be no way out, get on your knees and pray for Shackleton. Incomparable in adversity, he was the miracle worker who would save your life against all the odds and long after your number was up. The greatest leader that ever came on God’s earth, bar none.

Sir Raymond Priestley, who was part of Antarctic exploration teams with both Scott and Shackleton