Gregory Edmund

From The Archive:

THE GREAT PEARL SENSATION OF 1891

Like many of our readers, I took great delight in reading the now cherished memories of the late Anthony Flinders Spink, particularly in his fascinating personal accounts of the Spink of yesteryear. It prompted me to wonder what other stories could be told from our archives? Are there any historic skeletons to be found in the closet over centuries of business? What came to light has to be one of the stranger moments of intrigue in the long and illustrious history of the Spink brand, vividly recounted across the contemporary Penny ‘dreadfuls’ by editors keen to satiate the appetite of their burgeoning Victorian readership. Here, set out in diary format, is the complex and complicated story of the ‘Great Pearl Sensation’ of 1891, and how Spink ultimately challenged a UK legal edict dating back to the reign of Henry VIII.

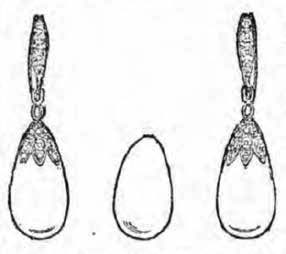

Wednesday, 18th February 1891, Mrs Georgiana Hargreave of Collingwood House, Shirley, Torquay discovers that her box of jewels is missing from a secret drawer in her room. The cache comprises “a pair of Brazilian pear-shaped diamond earrings, two pear-shaped filbert pearls, two smaller diamonds and some brooches, valued at £800.”

Thursday, 19th February, police enquiries establish that items matching the description are sold on this day to Messrs Spink and Son of London.

The trial

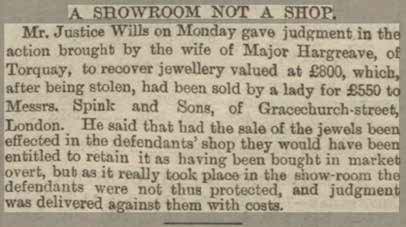

Friday, 30th October, enter Mr Justice Willis of the London Guildhall, presiding, and Mr John and Charles Spink, noted jewellers of Gracechurch Street, defendants. At the opening of the hearing, Spink acknowledges the purchase for £550 of some jewels on 19th February 1891, but contends that for Major and Mrs Hargreave to make a claim against them they need to bring a prosecution against the supposed thief with whom they had had dealings. What follows must be one of the finest twists of court jargon, perhaps equalled only by the most recent of political events. The prosecution’s council Mr Lockwood countered that as the sale had not taken place in ‘a market overt’ (for it was in an upstairs room not open to the general public), this legal obligation did not apply. In effect, the opening argument for the prosecution was: John’s business had been conducted in a private showroom, not a recognised shop, and therefore Messrs Spink and Sons were obliged to return the jewels to Mrs. Hargreave! Justice Willis retires for the weekend to consider his verdict.

The initial verdict

Monday, 2nd November, Justice Willis sums up the evidence: ‘There could be no doubt that the sale took place in an upstairs room. Could the showroom in which the sale of the jewellery took place be called a shop?.” No.

“He thought it an unreasonable stretch of language to say that a show-room, which could only be approached by the permission of the defendants or his servants, could be called a shop.” Judgement in favour of Mrs Hargreave, with costs, jewels to be returned.

Wednesday, 4th November, Spink appeals to Court to request that they retain the jewels, unless Major Hargreave can promise settlement of £500 out of his own pocket if they are again mislaid. Spink argues that Mrs Hargreave cannot be trusted to not be careless again! Court refuses ‘monstrous request’.

Thursday, 5th November, Spink and Son write to the Editor of the London Evening Standard: ‘It would appear, as a result of this decision, that where property of value, of whatever description, changes hands, it is only upon the ground floor and in the view of the public that such transactions can be held good in a Court of law. As this Act was passed as far back as the time of Henry VIII, when doubtless, business transactions were almost wholly carried out on the ground floor, is it not time either to repeal it, or modify it in accordance with modern requirements? We are, sir, your obedient servants, SPINK and SON”

The plot thickens …

Saturday, 7th November, “There seems to be more in the case of Hargreave vs Spink than has appeared in Court … the action tried by Mr Justice Willis last week was undertaken, strange as it may seem, for the purpose of clearing Mrs Hargreave’s young friend’s character. The latter at the time of this unhappy occurrence, was engaged to an officer, who most honourably stood by his word and married her in face of the awkward story, of which he had full cognisance. But the evil tidings had spread throughout society, and the ladies of the Regiment sternly refused to call upon the bride until the whole imbroglio was set straight. It is stated, however, that an action for libel will be the final outcome of this deplorable business, and that Sir Charles Russell’s services have already been retained.”

The mysterious ‘thief ’ unmasked

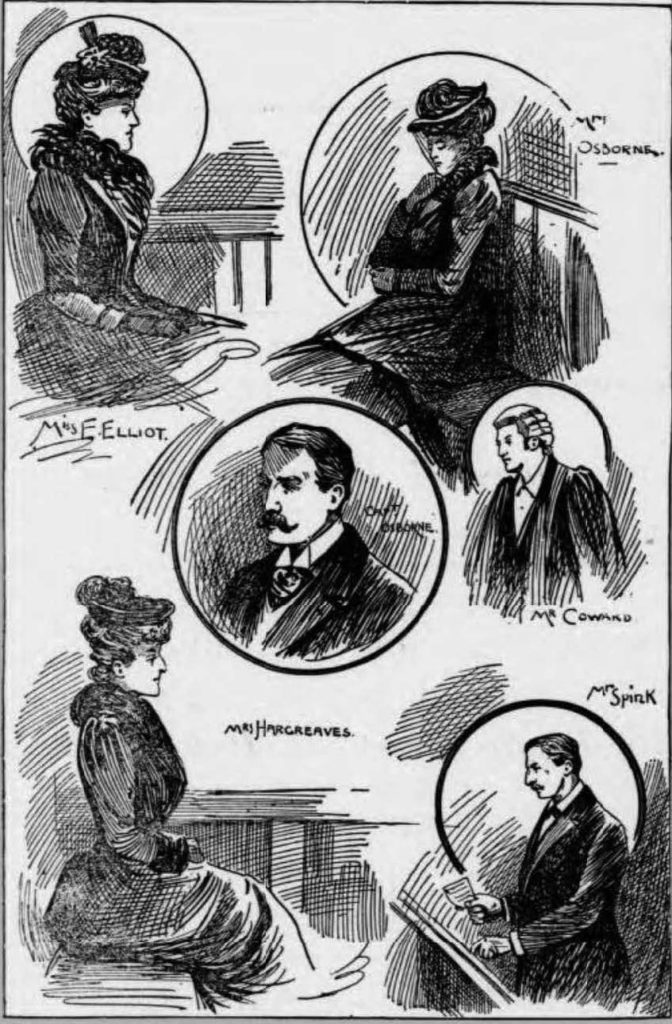

Thursday, 26th November, the Queen’s bench was summoned to hear a subsidiary charge in the case of Osborne vs Hargreave, following libellous accounts by a Mr Ames in his The Dwarf publication about Hargreave.

The court heard: “Upon identification of the lady who sold the jewels to Messrs Spink, Mrs Hargreave wrote to her young friend, and volunteered to hush the matter up if a sum of £1,000 was paid to her. The young lady at once communicated with her brother and fiancée [a Captain in the Carabiniers] who in their turn consulted [the legal counsel of] Messrs Wontner, who responded to Hargreave with their own action of libel unless the ‘foul aspersion’ was withdrawn. Hargreave reputedly send a further two letters demanding £750 and £550 to merely indemnify Messrs Spink.” Hargreave demanded an apology from Ames stating that: ‘the serious part of his paragraphs had no foundation in fact.” Parties happy to accept apology and payment of their costs as a conclusion to this legal proceeding.

High society turns on one another

Tuesday, 15th December, an action begins by Mrs Florence Ethel Osborne (daughter of Sir Henry James Elliot), to recover damages for slander from the defendants Major and Mrs Hargreave, the plaintiff ’s second cousin, for an allegation that she had stolen Hargreave’s pearls and diamonds and sold them to Spink and Son. Osborne claims not to have been the lady who sold the jewels to Spink, nor had the attire or ability to be present at the time the cheque was supposedly cashed, despite being identified as the vendor by Spink and two employees, Mr Baggallay and Mr Busk, and a bank teller. Mr Justice Denman presides over the case.

Wednesday, 16th December, accusations of Osborne being in debt at the time of the supposed theft are raised, but a detailed account of her attire on the supposed days of the visits to Spink or the bank where the cheque was cashed show discrepancies in the established timeline. Major Hargreave in cross-examination reveals that his wife has recently ‘lost’ jewellery in the garden at Collingwood House, and that he himself previously wanted the pearls sold because his wife could no longer have worn such jewellery.

Friday, 18th December, Major Hargreave is reported as saying ‘he would commit any crime for ‘oof ’ [Afrikaaner slang for coin]. He denies ever having used the statement. It subsequently transpires that Osborne’s brother-in-law Captain Geach, 4 Dragoon Guards, has previously sold his coin collection to Spink in late 1887 or early 1888. The case for the plaintiff closes. The case for the defence begins. Friends of Mrs Hargreave testify to her growing concern in the immediate aftermath of the theft about the guilt of Osborne, particularly as she is the only candidate in the family in London at the time of sale to Spink.

Christmas to bring a resolution to this case. Commentators add: “At this moment, it is with Messrs Spink that sympathy most goes, for Mrs. Hargreave has got her pearls back; but they who purchased them according to the custom of their trade, have been muleted of more than £500, by a technicality.” Proceedings are adjourned upon presentation of a mysterious letter to the bench.

An emergency statement

National Provincial Bank in St James’s Square furnished seven Fifty Pound notes to the mystery individual, and upon ascertaining serial numbers, traced one of the notes to a payment of an invoice for a linen. As was customary at the time, the note was signed to validate authenticity. This note bore the name of one Mrs Osborne. Following the shock result, Spink seek reimbursement for loss.

Friday, 25th December, City Police issue an arrest warrant for Mrs Ethel Florence Osborne, aged 26, 5ft 5in.

Sunday, 27th December, The Dwarf obtains an exclusive interview with Mrs Hargreave on her return to Torquay. When requested to show ‘the famous pearls’, she responds with ‘a mischievous twinkle in her eye, that she is unable because she has taken precautions to ensure their safe storage.” Major Hargreave produces a letter evidently written by Captain Osborne confirming his wife’s guilt and the subsequent dispatch of a cheque to Spink out of his pocket.

Friday, 29th January 1892, friends of Mrs Osborne send £550 to be paid to Spink. Spink is reimbursed a further £674 for costs incurred in the litigation against Major and Mrs Hargreave.

Thursday, 4th February, 9:15PM, Mrs Osborne arrives at Dover and is immediately arrested.

Thursday, 11th February, facing a charge of perjury, Mrs Osborne is remanded in Holloway Gaol. Mrs Hargreave visits her there.

Wednesday, 9th March, Florence Ethel Osborne pleads guilty to petty larceny and wilful perjury. Despite protestation from her victim, Mrs Hargreave, she is committed to nine months imprisonment with hard labour.

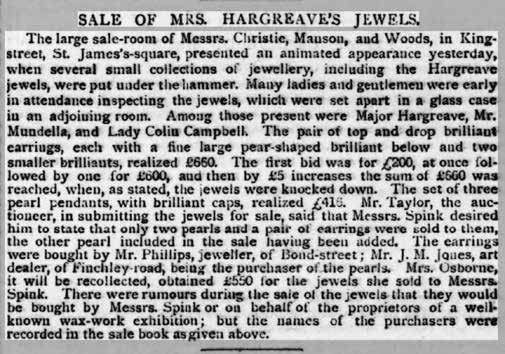

Monday, 28th March, the Preston Herald reports: ‘The sale of the notorious jewels that played such a prominent part in the Osborne-Hargreaves case attracted immense crowds to Messrs Christies’ well-known mart in King Street, London this afternoon. The catalogue said:

42. A pair of top and drop brilliant earrings with a fine large pear-shaped brilliant below, and two smaller brilliants above.

43. A set of three pearl pendants with brilliant caps. The jewels lay in a glass case, which both before and after the sale was surrounded by a large crowd. There is a popular superstition that pearls bring illluck, but nevertheless bidding was so keen that they realised an aggregate sum of £1,066. Mr Phillips, the Bond-street jeweller, was the purchaser of the first lot, and the second was knocked down to Mr Jones, also a jeweller. Messrs Spink and Sons, who bought the articles from Mrs Osborne for £550, stated publicly, through the auctioneer, that they only received two pearls and a pair of earrings.”

So that is the jewels resolved, but how about the protagonists? A petition was quickly established in the aftermath of her imprisonment to petition for Mrs Osborne’s early release, with widespread reports of her pregnancy adding to a sentiment of clemency amongst the 4,000 people who signed the appeal. However Captain Osborne, who had dutifully defended his wife throughout proceedings, found the task of family life and his army career untenable, reportedly offering his resignation in May.

The Sheffield Independent reports in January 1894 that following relocation to Wales, Captain and Mrs Osborne have been delivered of a child, and that Mrs Hargreave and Mrs Osborne are friends again. As the old adage goes: all’s well that ends well!