Gregory Edmund

MURDER, MONKS AND MASSACHUSETTS: THE EXTRAORDINARY TALE OF CHARLES PARTON

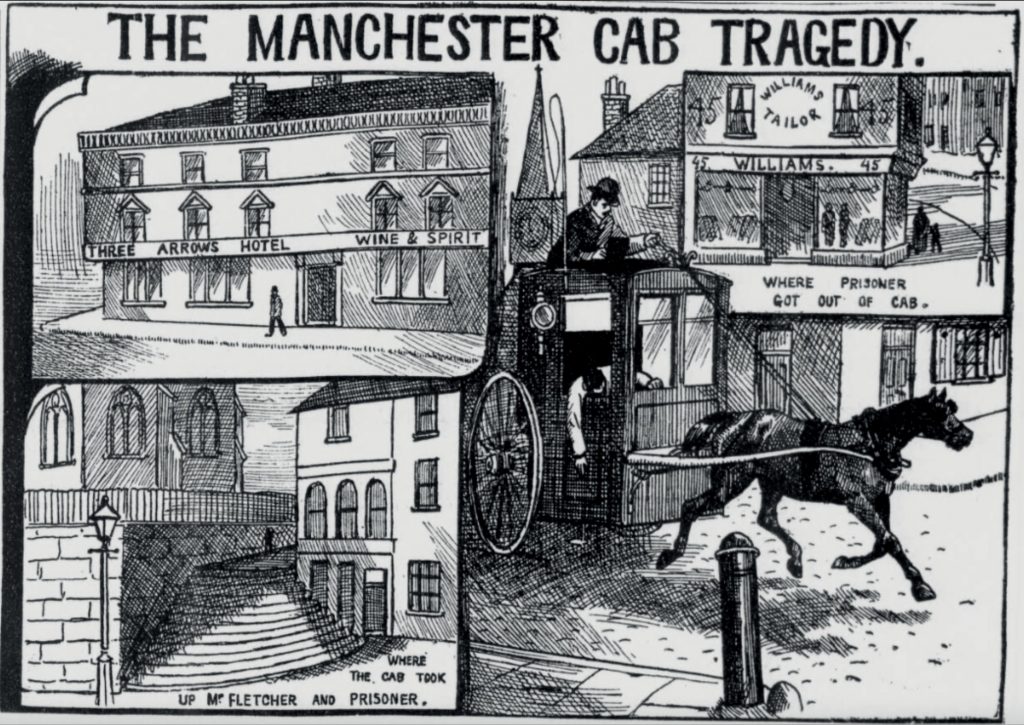

Shortly after his visit to the Philadelphia Mint, John Robert Fletcher would be summonsed back home to Manchester, to confirm the identity of a body. It would be his uncle; the retired managing director of the fam- ily firm of paper manufacturers now under his stewardship. John Fletcher had died slumped in the back of a hansom cab shortly after 9 o’clock, on the evening of Tuesday, 26th February 1889.

Only that day, both had been together at their company offices at 14 New Cannon Street, with the elder departing shortly after 1pm. Fletcher senior had recounted his plan to meet ‘an Old- ham gentleman’ around 4pm, before a trip to the Mitre Hotel to witness a public sale. With no signs of physical violence on his body, sudden death could easily have been natural cause; the victim simply tarnished as a ‘heavy gin drinker’ and stricken by the early stages of heart disease.

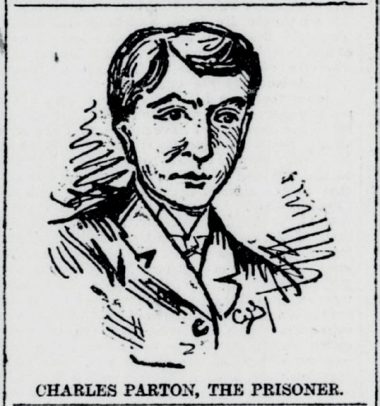

An autopsy by Charles Estcourt and Dr Julius Dreschfeld would however reveal traces of chlo- ral hydrate in the stomach and intestine – this, twinned with a missing gold watch valued at over £100, ensured that an investigation would be opened by Detective Inspector Jerome Caminada. Contemporary ‘Penny Dreadfuls’, fuelled by months of ongoing speculation about the Whitechapel horrors, immediately seized upon the story. The insatiable public thirst for murder was heightened still by the recent release of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet. Caminada would swiftly be dubbed ‘Manchester’s Sherlock Holmes’. His impressive knowledge of local criminal networks, their involvement in boxing matches, and habit of drugging sparrers with this chemical to rig fights led him to the character of 18-year-old Charles Parton.

Although the Fletcher and Parton family collision course would fatefully play out on the streets of Manchester in February 1889, their paths could quite easily have crossed before. Parton’s early life had been riddled with short custodial sentences. His first recorded offence came at the age of 11 in 1881, and resulted in 14 days detention at HMP Strangeways for non-payment of a railway fair. At 16, he was incarcerated for another six weeks at HMP Leicester for stealing jewellery. Shortly after his release in May 1887, he would have a severe disagreement with his father, a well- known pugilist and publican known as ‘Pig Jack’. Charles’ own participation in boxing was forbidden, because his father had wanted a better life for him and his older brothers. He flew into a rage upon learning of Charles’s bout with Denny Rhoen at the Free Trade Hall, near Manchester, during an exhibition by boxing-royalty Jem Mace.

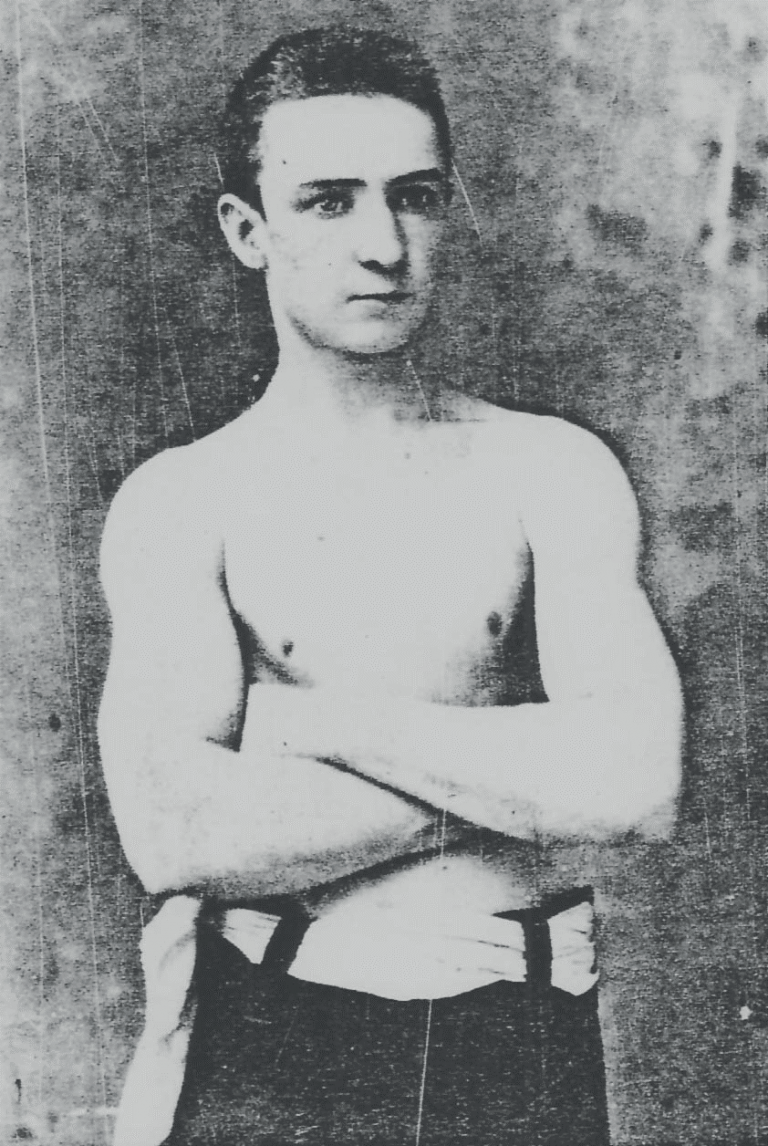

Shortly thereafter Charles fled to Boston, Massachusetts to stay with family friend and well-known trainer Patsy Sheppard. On Monday, 12th December 1887, Charles would stage his first official fight against Jack Lyman, whom he would best by technical knockout after 2 minutes 45 seconds. A witness to proceedings that day was rising bantamweight star George E Dixon. A bout was scheduled between them for Friday, 20th January 1888. In preparation, Parton sparred with fellow Englishman Tommy Coban, during which he broke his right hand. Despite being improperly set, he proceeded to fight Dixon. In the second round, his hand broke again. Advised to retire by referee Jack Williams, Parton thought he would be able to ‘go the distance as it was only a 10-round bout’ priced at $75. Four rounds later, the audience of Tom Earley’s ‘Sky Parlour Boxing Saloon’ consisting of Harvard College students forced the fight to stop, with the official record stating Parton ‘TKO’d in the sixth’. Dixon, affectionately nicknamed ‘Little Chocolate’, would go on to become the world’s first black boxing champion in 1890, and is credited with the creation of ‘shadowboxing’. His premature death in 1908 left his legacy to be largely overshadowed by the simultaneous rise of the heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson.

Meanwhile, travelling in the 1st Class Cabin of the SS Celtic was John Robert Fletcher, the third generation of a dynasty of successful paper manufacturers established in 1830 at the Kearsley Bleachworks, in Stoneclough, Greater Manchester. He would disembark in New York on 10th October 1887, armed with his father’s fresh UK patents for further improvements to dyeing tissue that he sought to bring to the lucrative American marketplace. Already under his firm’s belt were the Highest Accolade from the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition (1876), a Prize Award from Paris International Exposition (1878); and two Gold Medals from the London (Crystal Palace) 1884 and (Alexandra Palace) 1885 Exhibitions. He brought with him a personal knowledge of the white ‘satined’ and coloured tissue papers, ‘bible paper’ and the domestically well-known ‘grass-bleached’ tissue – found to be the perfect wrapping for silver and plated goods preventing their scratching and tarnishing, and already a veritable hit in the jewellery quarters of Sheffield and Birmingham.Unfortunately, not even a month into his trip John Robert’s father would pass away back in England. James had championed the international expansion of the firm and had jealously guarded the company’s monopoly on the firm’s renowned paper quality. One company anecdote records James’ personal pursuit of a cheap influx of high-quality paper from a rival producer on the continent. An exhaustive search tracked down the source to a single mill in Russia, equipped with a more advanced 12- roll Swiss-made sheet cutter machine. Upon his return to Lancashire, James ordered an example to update his own paltry single roll cutter and through commercial acumen saw off this cheaper import.

Back in 1864, James had been a vocal petitioner to Parliament to reinstate the duty on imports of foreign paper because their greater abundance of raw materials was flooding the English market place. Despite losing the motion in House of Commons the following May, James shrewdly chose to specialise in the satined white and coloured tissue papers that his son would take to Philadelphia and New York in the following two decades. His interest in America had been longstanding, having represented the Liberal party prior to the Civil War, but in coming to sympathise with the Confederacy realigned himself domestically with the Conservative party after 1865.

‘By Conservatism I do not mean the conservation of abuses but the preservation of what is good.’ James Fletcher, December 1866

The beginning and end of John Robert Fletcher’s US visit would therefore be punctuated by family tragedy. As final preparations were made for the internment of John Fletcher, the description of a man seen with the deceased at the time of hailing the cab of Henry Goulding provided the grounds for Charles Parton’s arrest at his father’s residence, 3 Moore Street, in the early hours of Saturday 2nd March. His beardless and youthful appearance further matched the description of a thief who had made off from Liverpool chemist Charles Bromley with one pound weight of chloral on Tuesday, 19th February 1889. Other key witnesses would confirm sight of Parton with Fletcher just after 5pm outside Sinclair’s Oyster and Shell Fish Shop, and later at the Three Arrows Inn for 20 minutes, during which time Parton had been seen administering a vial of yellow liquid to the beer they were drinking together. At the time that witness considered it a medicine, and neglected to mention it to the barkeep or the Police Constable passing in the street outside.

‘The greatest interest was manifested in this case, three special trains were run from Manchester and Preston for the occasion, and for over two hours previous to the time fixed for the hearing (half- past ten) the entrance to the hall was besieged by a crowd of people “of all sorts and conditions of men” and women, who desired to get admittance to the court. Those who were favoured by orders from the Sheriff were passed into the place, and before the beginning of the trial the Sheriff’s box and the grand jury box were filled by a body of well-dressed sensation seekers, mostly of the fair sex.’

Day One of the Trial, Liverpool Echo, Monday 18th March, 1889

Parton would confirm spending time that evening with Fletcher, excusing it as a passing association fostered during his employment as a messenger at the Mitre Hotel where the businessman had stayed. Under pressure he would admit to administering the chloral, but did not accept that alone had killed Fletcher. However, damning character testimony was presented by the prosecution as further charges for similar poisoning and robbery attempts were made on railway-porter John Parkey and grocer Samuel Oldfield. With further testimony from the night of 26th February attesting to Parton ‘flourishing a gold watch at 7.25pm’, the Jury unsurprisingly returned a guilty verdict.

However their recommendation for clemency due to the age of the defendant was not able to be passed on by an admittedly sympathetic Judge. In outline to the jury pre-trial, inadvertent death by poisoning was still murder in the eyes of the law. Consequently a sentence of death was carried on the second day of trial, 19th March 1889, at nine minutes to two o’clock, only three weeks after the alleged crime had been committed.

‘Mr John Robert Fletcher was the first witness called, and he said he was the nephew of the deceased, whom he had last seen alive at 14, New Cannon Street, at a quarter-past one on February 26. He was then perfectly sober, and had on him a massive gold curb chain and his watch, which was a valuable one. Witness had seen the body at the infirmary the following morning. Deceased had lately been in good health, and as far as the witness knew, he was not acquainted with the prisoner. He occasionally got drunk, but he had never remonstrated with deceased for drinking. He was suffering slightly from heart disease. He was a big, stout man about 6ft in height, but during the last twelve or fifteen months he had got thinner. He was a generous man, and kind in many ways, and was in the habit, when under the influence of drink, of treating people to drink, but he was not in the habit of speaking to strangers.’

Day One of the Trial, Liverpool Echo, Monday 18th March 1889

The court of public opinion however remained divided, with the Congleton and Macclesfield Mercury slamming Parton as ‘an uneducated man, with an imperfect intelligence, who could seize a suggestion of crime from a story and carry it into effect.’ Much like the paranoia today about the influence of video games in the rise of violence amongst children, the editor would evidently see a similar nefarious influence in the publication of murder mystery books! Given the widespread knowledge of the noxious aftertaste met with chloral ingestion, The Empire News andThe Umpire would further comment, with no hint of irony, on the eve of trial: ‘During the last few days of his incarceration at Town-hall cells, Manchester, Parton was very ill and not allowed to take exercise in the cell corridor. It is asserted that by a good natured officer he was supplied with a pint of bitter beer, warmed and made pleasant by the addition of a little ginger. Parton is said to have been in terrible agony.’

The Liverpool Echo would further fan the flames by reporting the prisoner’s ‘extraordinary callousness’: ‘On the jury retiring to consider their verdict the prisoner leaned over and made a request to his solicitor and counsel to the effect that he might be allowed to leave the dock and “go down”. This request, as it happened, was prompted by the knowledge that an excellent dinner had been prepared for him at his friends’ expense. Parton was quite aware of the fact that as a convicted prisoner he would not, according to strict prisoner rules, be allowed to eat the meal in question. He was taken below, and while the jury were weighing his fate in the balance, the doomed man was consuming the viands prepared for him, his last meal as an unconvicted prisoner.’

An appeal naturally followed, with a Leicester pathologist questioning the quantity of chloral hydrate found. In their assessment the amount would be insufficient to kill a foetus, let alone a 60-year-old man, and they duly assessed the primary cause of death to be the result of syncope. The Home Secretary, Sir Henry Matthews, in communication with Mr Justice Charles, ascertained mitigating evidence supporting Parton’s defence and ignorance about the potency of the drug.

‘Dear Father and Mother, Just a few lines to let you know that I am better than I was. I never thought of coming to this, but it is the will of God! It can’t be helped now. Dear mother, you must not fret and cry for me, for we must all die some day; so keep up your heart and don’t forget to come down on Monday, along with Augustus and Maggie, to see me. Kiss all the children at home for me, and tell William he must be a good lad. No more at present. I will tell you more on Monday when I see you. Good night and God bless you all, I am your loving son, Charles Parton’

22nd March 1889

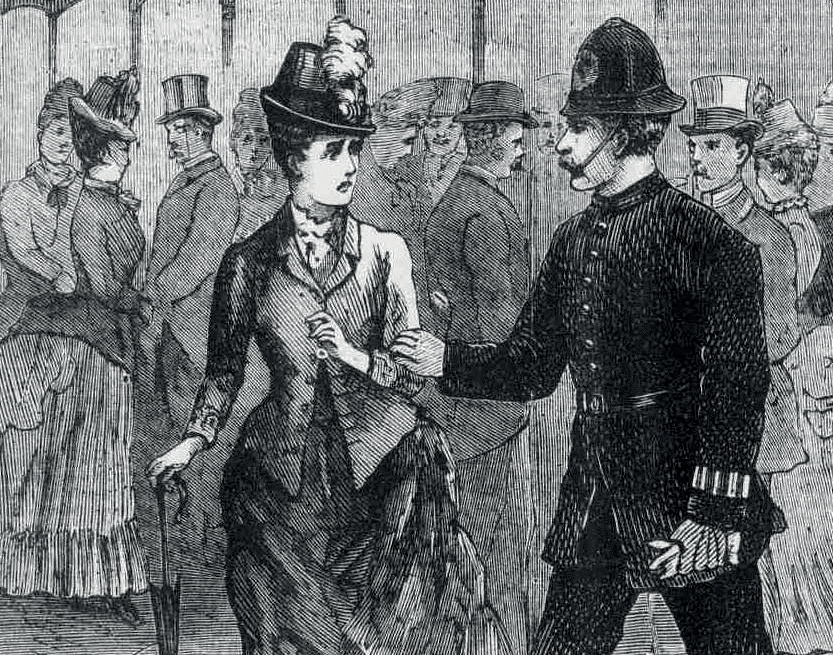

As a consequence his death sentence would be commuted to life imprisonment on 5th April, just four days before his intended execution. Matthews may have been induced to clemency given the political pressure he faced following several previous high-profile embarrassments including the notable ‘Miss Cass Case’ since his surprise appointment at the election of 1886. Perhaps he had simply leant towards populism, following the pardon petition by defence solicitor William Burton reaching over 5,000 signatures.

‘… If Miss Cass was as respectable as she claimed to be, she should refrain from walking along Regent Street at 10 o’clock at night…’ – Stipendary Magistrate Robert Milnes Newton

Parton would be released on licence (CRO No. 2667-00) from HMP Dartmoor on 1st October 1900 as a stonemason labourer, intent on returning to Manchester. Scarcely two months later, alongside Mary Smith, alias Elizabeth Higgins and Margaret Sheehan, Parton, now a hotel waiter, returned to criminality by relieving a gold watch and chain from a Mr William Hickling at Kingston-upon- Hull. Unlike his last court appearance, Charles pleaded guilty and was sentenced to ten days imprisonment. Unfortunately a new conviction resulted in recall to serve an additional three years on his original 1889 sentence at HMP Parkhurst. He would be liberated on second licence on 29th January 1904, with the Liverpool Daily Post quick to update its readership on the famous ‘Manchester Cab Murderer’. No sooner had he gained his freedom did the one man crime wave take himself to a Salford fairground, where he happened upon a seven-year-old boy.

Borrowing from him a penny, he asked the boy to guess its location after a coin toss. A correct guess returned the penny to the boy. The trick was then repeated with the boy’s shilling. Although this time instead of hiding the coin in his palm, he secreted it in a sleeve When the boy guessed wrong, Parton claimed the shilling and dismissed the trick as ‘a fair bet’.

Astonishingly the magistrate accepted this account, and Parton was discharged.

‘A fair bet, forsooth! One might with more reason regard thimble-rigging and the three card trick as honest games – indeed, I do not see how this sapient magistrate can logically punish the thimble-rigger and the card-sharper after this amazing decision.’ Truth, 21st April 1904

By his own account, Parton then relocated to Buenos Aires, via failed sea voyages to Canada and South Africa. He only returned to Britain following the outbreak of Great War hostilities, now under a passport in the falsified name of Charles Mack. He hoped rather naively that undertaking patriotic military duties would lead to a pardon from his ‘indefinite life sentence’. The day after disembarkation, 12th December 1914, he enlisted into the 10th Devonshire Regiment under the new alias Owen Evans (Service no 50345).

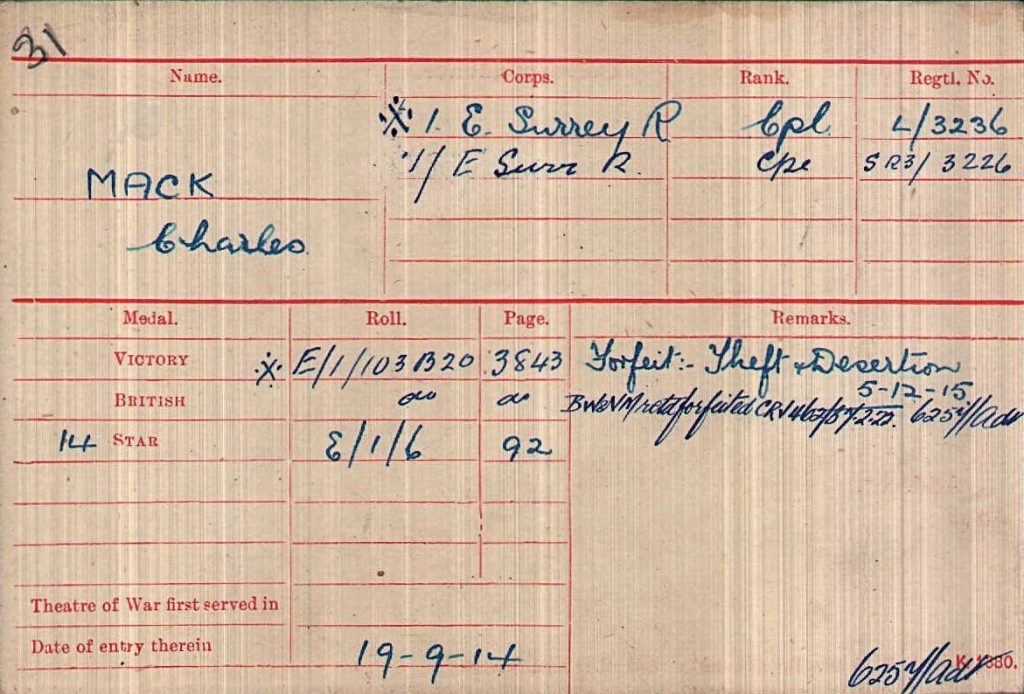

Posted to train at Bath and now aged 45, he would meet ‘poor but respectable local girl’ Mary Jane Curtis who had turned just sixteen on 6th January. On 3rd April 1915, Parton and Curtis would wed at Bathwick Parish Church, with the official register recording the details of his passport name and fictional father ‘rancher, Charles Mack senior’. On 8th July 1915, Private Owen Evans deserted ‘after being recognised as one of the Partons’. Relocating to London, he would re-enlist as a private soldier into the 4th East Surrey Regiment. By sheer coincidence, the East Surreys were actively dealing with another deserter also called Charles Mack (Service no L/ 3236) who would go by various aliases including Charles Daniel MacNamara and William Bennett.

This ‘Old Contemptible’ had returned from France suffering the ill effects of syphilis on 29th January 1915. Admitted to No 8 Casualty Clearing Station at Bailleul, he was transferred home to convalesce until 20th February. On 18th April, Corporal Mack would go AWOL, eventually being captured on 27th July. Court martial resulted in his imprisonment for 112 days and demotion to the ranks.

His six years of service in the reserves would also be struck from his record. Returned on 23rd October 1915, he would be docked 14 days’ pay and given Field Punishment No 2 from his Commanding Officer. Two days after completing this sentence, on 5th December, Mack deserted again, and was ultimately dishonourably discharged on 29th February 1916, having ‘been convicted by civil authorities attempting to pick pockets’.

Bizarrely Parton’s own experiences that autumn would closely mirror his assumed namesake, as his past life was never far from casting its long shadow. Just weeks after his own re-enlistment, two fresh allegations of theft were levelled against him at Euston and Liverpool Lime Street stations. Subsequent searches relocated the stolen articles at a lodging house where Charles and Mary Jane stayed. After being apprehended, Parton affected a successful escape from custody whilst the train he was on was being shunted. He was rearrested, identified as the carrier of a misappropriated suitcase valued at £82.4s.6d, and brought to court in his khaki on 7th October 1915. On 5th January 1916, Charles Parton, alias Owen Evans, was convicted of larceny and sentenced to three months imprisonment. Once more his original 1889 sentence became active, and a further three year custodial sentence was added to his term at HMP Portland.

On 21st March 1919, he was released under third licence, whereupon he was immediately arrested by military authorities. Discharged back to barracks, money troubles continued to plague the unemployable Parton, as he was reduced to begging with his CO for money when sent on leave, and further requesting the Army recompense him the £6.0.0 for his travel back to Argentina where he at least had a steady job on the Railways. Parton would be forced to prioritise his demobilisation. He achieved this on 8th May and returned to his loyal wife, who had stuck by her husband throughout his most recent bouts of criminality. When a Bath journalist accidentally crossed paths with him in September 1919, Parton would finally be in receipt of the £6.0.0 Argentina ticket, but lacked the gratuity payment he needed to actually return overseas. He was therefore forced to rent a handcart and scales to hawk fruit and vegetables.

At home, Mary Jane would achieve her own victory in the rectification of their marriage certificate. On 30th March 1920, in the presence of the Parish Clerk and Rector H F Napier, Charles Mack revealed his true identity as Charles Parton and signed in recognition of this update to the official record.

‘My wife is a very delicate consumptive and one of the best wives in the world, and she is respected by all who know her. She is a good wife, a good mother, a clean living woman, and lives in the fear of God. Would to God had I never married? I never intended to, but therein hangs a tale. I have done my best to keep my family respectable. My children have never known want of food; but my poor suffering wife and I have known the pinch of hunger many times. Nor am I ashamed to say so.’ Charles Parton, 13th August 1921

At Christmas 1920, Parton pitched a stall at Sawclose, Bath, encouraging passing patrons to toss pennies to win prizes. In Parton’s own words,

‘They had the choice of ladies’ bangles, a gents’ watch-chain, fountain pens, safety razors, mouth organs, all of which the people were satisfied with and acknowledge them good value. But Detective Marshfield thought otherwise. He told me it was a swindle, a game of chance and told me to pull my stall down.’

On 28th July 1921, he would once again feel the long arm of the law, as he was arrested on an allegation of stealing the overcoat of Mr R H Collingbourn at Brinkworth, valued at £3.10.0. Despite protesting his innocence at the scene, and Parton’s further impassioned plea at court for the end of indefinite sentences, he would be committed to trial on 13th August. The Police Gazette (17th October 1921) records his subsequent re-conviction at the Wiltshire Quarterly Sessions, resulting in a further six- month imprisonment at Dartmoor. However his plea would not fall entirely on deaf ears, for no additional term was added to his new sentence, resulting in his release under fourth licence on 19th June 1922.

But 14 months later, Parton would be once again up in front of the magistrate for ‘use of bad language towards his brother’. Objecting to the initial magistrate on grounds of his having presided over his previous conviction, Parton’s defence laid out that ‘his brother was a dog, and not a man, who had not only robbed [Parton] of his home while he was doing penal servitude but had also permitted their sister to die in the workhouse’. A fine of 20s was imposed on that occasion.

On New Years’ Day 1924, Parton would be seen causing a disturbance on Union Street that caused an obstruction to traffic. Witnesses alleged that Parton, now a balloon salesman, caused a quarrel with a rival trader named ‘Walker’. Proceedings then descended into chaos as Parton’s promised ‘courtroom of character witnesses’ transpired to be a 50-year old fellow hawker named Patrick O’Shea, who stated that he would only give evidence if Parton paid him 6s.6d. Parton ill-advisedly responded, in full view of the court, that ‘he feels more like giving him a punch on the nose’. Fortunately both Jury and Judge saw the lighter side of this highly prejudicial comment, but the latter would take umbrage with Parton’s subsequent acclamation that ‘Guilty or Not Guilty, that man would send me to Gaol’. To which the Judge snapped back: ‘Keep quiet and don’t break the Corporation furniture’.

‘I was only 18 when I got ‘life’. They had the best of my days; they might as well have the rest.’ Charles Parton, December 1925

In April, Charles would appear again on another charge of obscene language, this time choosing to interrupt PC Holbrook while he was giving evidence by branding him ‘a liar’. Parton would again refuse to take the oath while in the witness box, claiming to be ‘a fatalist, who does not believe in Christianity’, opting to further besmirch the character of the Bath Board of Guardians as ‘not very intelligent people’. In December 1925, Parton ‘pitched’ his wares of ‘patent medicines’ by the Southampton dock gates, but was once again ‘hounded’ by the Police. A similar set-up in the market square would be disrupted by jealous locals so much that a careless lady’s purse proved too tempting to ignore. Once more summoned to Police Court, he was found guilty and sentenced to three months hard labour.

“Mrs Parton described her husband as the best man living when he was away from the drink and evil companions, whom she blamed for his lapses. He is passionately fond of the children, and always sent what money he could while away from home. While in London he tramped the streets hungry, after sending them all he had.” Somerset Guardian, Friday 1st January 1926

In August, Charles would take his court protests to the streets, distributing pamphlets in Hyde Park that denounced the prison system and the policy of ‘ticket-of-leave’. Once more hauled before a judge for obstructing the highway, the Judge commended Parton for his ‘great natural eloquence’ leading to his dismissal with a warning. The following year would result in two further court appearances. Once in July for interfering with the Police while moving on hawkers, for which he was fined 20s, and the second in September for a violent assault on a taxi driver and the use of further obscene language outside a train station. Once more Parton was found guilty and fined £3.0.0.

Following this latest outburst, Parton retired to grounds-keeping work and gardening.

‘You are my greatest enemy, your one object is to send me back to penal servitude because I am showing the need for prison reform.’ Parton addressing the Chief Constable at Bath Police Court, 12th September 1927

However his neighbours would evidently continue to hang the past over Parton, for in September 1929 he would allegedly assault a Mr Butler and insult a Mrs MacGowan merely for ‘threatening to send me to gaol’. In February 1930, the monks of Downside Abbey admitted giving a job to Parton but that it was not ‘a sanctuary for him’. The following year, while changing gear near the Post Office, Parton fell off his motorcycle, face-planted the tarmac and was knocked unconscious. Despite recovering sufficiently to father another son in his 62nd year, clearly his injury had a debilitating effect on him. He was recorded as an ‘incapacitated pensioner’ on the 1939 Census whilst living at Hole Farm in Balcombe, near Cuckfield, Sussex. Surviving the Second World War, this incorrigible and unfortunate rogue finally passed away with the privacy he had so craved in Sussex in July 1947. Mary Jane would remarry a Francis Jonah Sawyer in 1953, and herself pass away in Surrey in 1972.

It is sheer chance that the attestation papers of both Charles Macks survived the Blitz, allowing us to decode this otherwise unbelievably complicated and coincidental duo. MacNamara’s medal index card records his service as Corporal with the 3rd Special Reserve Battalion of East Surreys, reckoned from 1908, through his arrival in France with the BEF on 19th September 1914 (Service no L/3236) with the further noted alias William Bennett – this being the name of a prosecution witness against him in an 1911 assault trial. On 29th January 1915, Mack attached to D Coy, 1st Battalion, was admitted to military hospital suffering from syphilis, transferred to No 8 Casualty Clearing Station at Bailleul, not to be discharged until 20th February. His MIC then records his desertion on 5th December 1915. He was dishonourably discharged from military service on 29th February 1916, ‘having been convicted by civil power of attempting to pick pockets, theft and desertion’, rendering his potential entitlement to a WW1 ‘Mons’ trio forfeit.

The John Robert Fletcher 1888 full US proof set will be offered for sale at Spink London on 15th September 2022.

For further information please contact Gregory Edmund,