“Palestine’s borders were always ill-defined, especially to the east where tillable land started to give way to desert regions populated only by nomadic tribesmen”

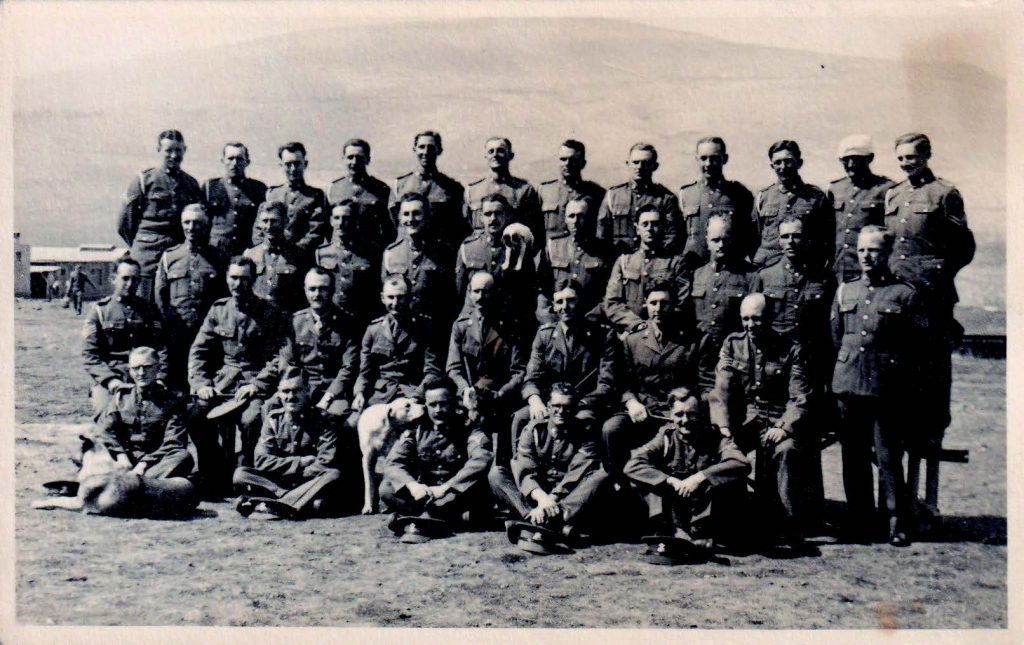

I was first drawn to the history of Palestine and its banknotes by the notes themselves – avidly collected of course, and issued by a now long gone authority in a region of great and continuing turmoil. There was, however, an additional reason – my father had served in the British Army in Palestine during the Second World War in C Squadron, the Cheshire Yeomanry. From the very little he ever told me about his wartime experiences he seems to have had a very quiet war and he is mentioned only twice in the Yeomanry’s official history – in the roll call of enlisted men and as a member of the Yeomanry’s rugby team. But the memories of that time did stay with him and always left me curious to know more.

This article looks at Palestine’s history, the role of the Cheshire Yeomanry in Palestine during the Second World War and the story of paper money in that divided land. Last, but not least, it also takes a look at the notes themselves

Palestine – Historical Background

Palestine’s long and immensely complex history goes back at least 5,000 years. The region had originally been known as Canaan but is later referred to as Palestine after the Philistines who had moved to the coastal areas of what is now Israel, Gaza, Lebanon and Syria around the 12th century BC. They were Semites, the ethnic group that dominates the region and includes both the Phoenicians and the Israelites – the Jews. Palestine’s borders were always ill-defined, especially to the east where tillable land started to give way to desert regions populated only by nomadic tribesmen. On most historical maps it lay well to the east of the River Jordan.

The twelve Israelite tribes of Hebrew scripture gradually achieved dominance in the region after the 12th century BC when the kingdoms of Israel and Judah were established. However, Egyptian armies under the Pharaohs invaded and by 1469 BC had conquered a Canaanite (Phoenician) army to establish control.

From 1150 BC King David started to reunite Israel and Judah, but conflict continued and Jerusalem, one of the oldest continuously inhabited human settlements in the world (it vies for the title with Damascus and Jericho amongst others in the region), was conquered by another Egyptian army in 925 BC. Egyptian rule was replaced by that of the Assyrians in c.720 BC and between 586 BC and 1517 AD Palestine suffered countless further invasions starting with the Babylonians, followed by Persians, the Macedonian Greek Alexander the Great, Romans, the Arab Rashidun Caliphate, Turks, Christian Crusaders and once again Egyptians. The Turkish Ottoman Empire invaded and imposed control in 1517 and Ottoman domination continued until the latter stages of the First World War in 1918 (with a brief interruption when Napoleon, having conquered Egypt in 1798, pushed north into Palestine).

y 1800 the Ottoman Empire stretched from Turkey proper through Syria, Palestine and what became Transjordan down to Aden and Qatar (although central Arabia remained outside it). It included Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Algeria at its height.

The population of Palestine prior to 1700 was overwhelmingly Moslem Arabs with small Jewish and Christian minorities. The persecution of the former led to widespread emigration and the creation of the Jewish diaspora across Europe and North Africa. Most Jews settled in the towns and cities.

However, Jewish yearning for their ancient homeland never waned and in 1700 Judah the Pious brought about 1,500 Ashkenazi followers from Poland and Germany to settle in Palestine. Many more were to follow in the 19th century and by 1895 Whitaker’s Almanac estimated that the Jewish population had risen to about 80-100,000 out of a total of 620,000 in the Ottoman province of Palestine. Jewish immigration accelerated in the 1870s under the auspices of Baron Edmund Rothschild, despite efforts by the Ottomans to deter it.

British influence in the region was evident in their control of the French-built Suez Canal and in 1882 the whole of the Ottoman province of Egypt was occupied by British troops. French influence had also grown in Lebanon and Syria and in 1916, during the First World War, the two European powers reached the secret Sykes-Picot agreement to divide the Ottoman provinces of Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Iraq into British and French spheres of influence.

While this agreement was superceded by the League of Nation mandates awarded to France and Britain in 1920 the modern border between Syria and Jordan still reflects the dividing line drawn on the map in 1916. In 1917 Palestine was occupied by British troops (including a Cheshire Yeomanry battalion) under the command of General Allenby. On 2nd November 1917 the Balfour Declaration was signed by the British Foreign Secretary, addressed to Lord Rothschild (the 2nd Baron) announcing support for a Jewish national home in Palestine. When the British mandate was established over Palestine, Jordan and Iraq it was designed to “secure the establishment of the Jewish National Home” while at the same time “safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine”.

Once the British began to administer their mandate areas they succeeded, despite their best efforts, in satisfying neither the Arab majority nor the growing Jewish population

They tried to maintain an even-handed approach to the conflict between Arabs and Jews although uprisings by one side or the other constantly tested their authority. By 1940, however, the mandate areas were largely peaceful.

Jewish immigration continued, and indeed further accelerated, despite continuing opposition from the majority Arab population. By 1935, out of a total population of Palestine west of the Jordan of about 1,300,000, some 355,000 were Jewish, 837,000 were Moslem 105,000 were Christians. Immigration in the 1920s was mainly from Poland and Germany but many more started to come from the latter due to Nazi persecution in the 1930s and 1940s. The British agreed to restrict further Jewish immigration without ever stopping it entirely.

After the war in 1947 the United Nations recommended the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Palestinian states with Jerusalem under international control, a solution fiercely rejected by the Palestinian Arabs. War broke out between Arab and Jewish forces and on the same day that the British finally left Palestine on 14th May 1948 the State of Israel was proclaimed by David Ben-Gurion.

The Cheshire Yeomanry in Palestine

Although the Cheshire Yeomanry had formed part of the occupying British forces in 1917 they stayed only until 1919. Their role in Palestine during the Second World War (with my father in their ranks as a Corporal) was of greater import. They were part of the 6th Cavalry Brigade and were probably the last regiment in the British Army to go into battle on horseback.

The Cheshire Yeomanry can trace its history back to 1797 when Sir John Fleming Leicester of Tabley raised a county regiment of light cavalry in response to the growing fears of invasion from Napoleonic France. In 1803 the Prince of Wales (later King George IV) gave his permission for the Yeomanry to wear his triple feather crest, which is still proudly displayed on their Guidon. The Yeomanry played an inglorious part in the Peterloo Massacre at St Peter’s Field, Manchester in 1819. A quiet century followed but the Yeomanry again saw action in 1900 during the Boer War in South Africa, their first overseas deployment.

Their first deployment in the Second World War was to Palestine. They and their horses crossed France by train and were shipped from Marseilles in January 1940. My father and the rest of C Squadron sailed in HMS Tairea, a troop transporter later to become a hospital ship. The regimental history records that the first part of the voyage was across the Gulf of Lyons in the teeth of a winter storm. My father insists he was one of the few not to succumb to seasickness which even afflicted some of the horses. Conditions must have been grim as his duties included cleaning them out! The ship arrived safely in Haifa on 9th January and he records that the weather on arrival was all too English – it was cold and pouring with rain!

The Yeomanry’s immediate task on arrival was peacekeeping, but first the horses (and men) had to be acclimatised. This proved anything but straightforward for the horses who had to get used to different feed – and more than one stampede was caused when a camel train entered the army camp. The horses had never seen camels before and didn’t like the look of them!

At this stage France had not yet been overwhelmed by Nazi Germany and the Italians were yet to enter the war but in June 1940 this all changed and security had to be tightened. New orders were finally received in June 1941 requiring the Yeomanry, with other troops under the command of an Australian brigade, to move north into what was now Vichy French- controlled Lebanon and neutralise their forces there. Some Free French forces were to join them. From Palestine the Yeomanry moved north and by July had occupied Lebanon south of Beirut. An armistice was quickly agreed. My father says he never fired a shot in anger at the enemy as they retreated faster than he and his colleagues could advance!

British and Australian forces took control of Syria too and gave my father the chance to visit Damascus where he bought a beautiful engraved silver dish still in the family and was able to practise his French on the Free French administration installed after the Vichy French surrender.

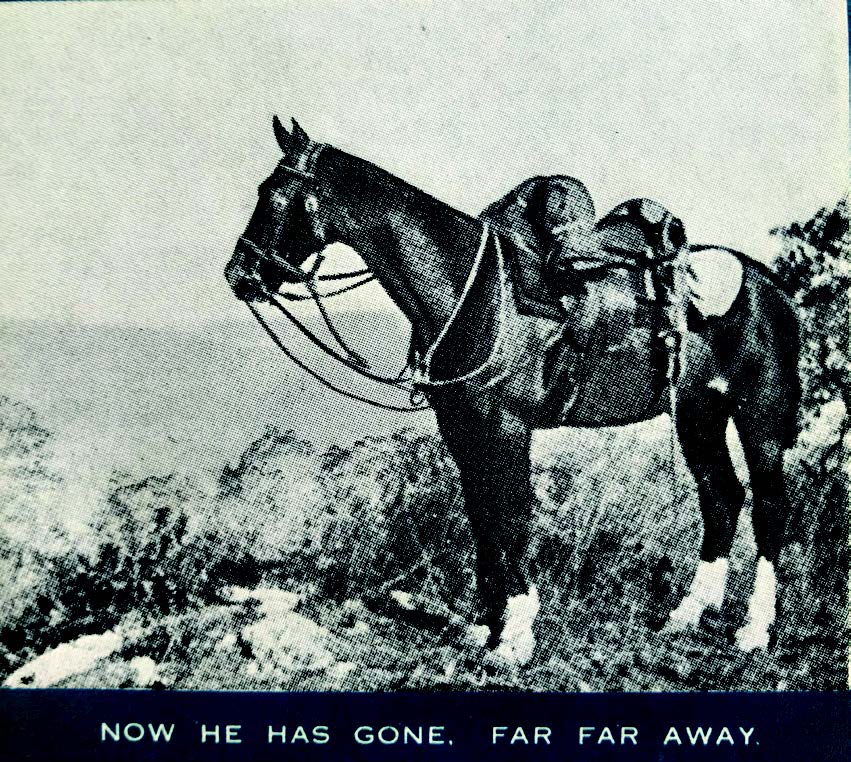

Although the horses had proved their worth in the mountainous terrain of Lebanon the Yeomanry was ordered to give them up in late 1941 prior to retraining as a Signals Regiment. 26th February 1942 was a sad day for all concerned as the cavalry troops were parted from their horses for the last time – “dehorsed” in military terminology. The fate of the horses was mixed – some had to be put down while others were sold to locals. Thereafter C Squadron stayed in Palestine for several more months before transfer to Egypt and then back to Europe in late 1942. My father retained fond memories of his time in Palestine and most especially for the incredible generosity of the local people he came into contact with. He did, however, leave with the firm intention never to eat another sheep’s eye!

The Currency History of Palestine

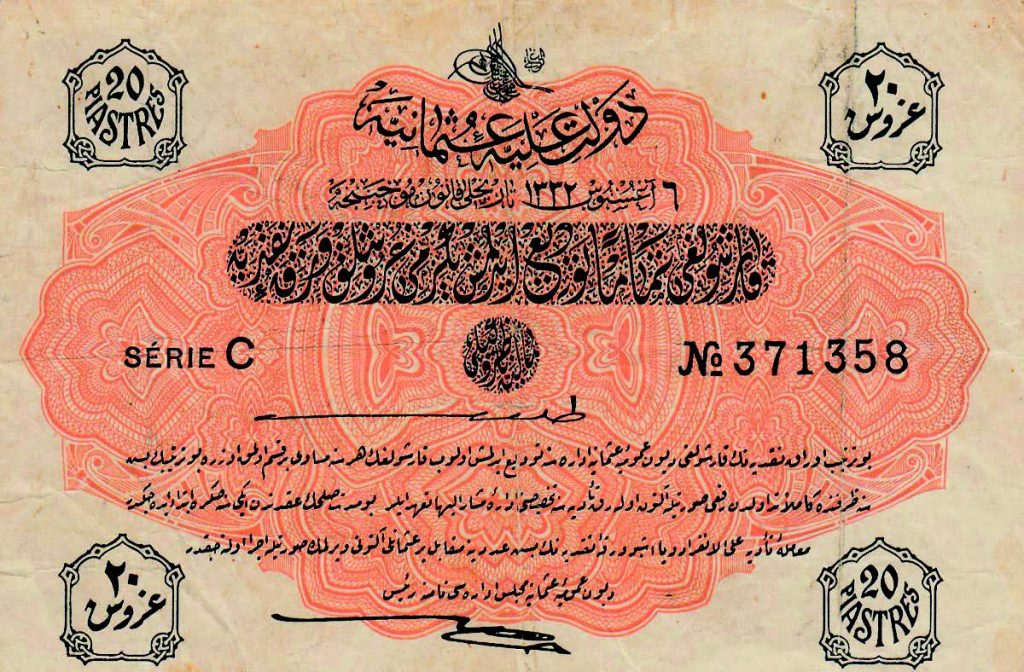

The coinage in use in Palestine during the Ottoman period was a complex mix of Turkish, Egyptian and European coins, the latter mostly British, French or Russian. Paper money was unknown until well into the 19th century. Larger commercial transactions would traditionally have been in gold coin but gradually a desire for paper money developed due to the impracticality of gold for larger deals. The first recorded use of paper money is in 1863 when it was introduced by the Imperial Ottoman Bank. The public did not realise at first that the notes were fully backed by gold but very slowly use of their notes increased until the First World War broke out in 1914. Ottoman paper money disappeared after their army was defeated by the British in 1917.

According to the 1912 edition of Baedeker’s Handbook for Travellers in Palestine & Syria the gold coins in circulation were either French, British, Russian or German (the latter at a discount) while the silver coins were mostly French or Swiss and “Egyptian money is refused everywhere”. The Austrian Maria Theresa silver thalers, although widely accepted, are not mentioned by Baedeker, nor is paper money of any sort. In 1917 the British made Egyptian notes and coins legal tender.

The dominant bank in Palestine during the British mandate was Barclays DCO (Dominion, Colonial & Overseas) who were the de facto government bankers. The bank had taken over the British-based Anglo-Egyptian Bank. Its first branches were opened in 1918 in Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, Nazareth and Tel Aviv and they banked (and employed) members of all communities. The DCO’s resident manager for many years was A P S Clark, a highly respected and trusted banker, sincere in his devotion to the country. He was an ascetic member of the Plymouth Brethren who ran the country’s branches until retirement in 1955. Their Allenby Square branch in Jerusalem also housed the Palestine Currency Board and was occupied by Jewish irregular forces in 1948 thanks to its strategic location. It briefly became a machine gun post (see photo).

Paper currency in the British mandate area was first provided by a subsidiary of the Jewish Colonial Trust, the Anglo-Palestine Company (later Bank) who issued “registered cheques” in French Francs. These circulated as currency from 1914 to 1922. Due to a shortage of small change during the First World War there were also some local informal paper issues by organisations such as Jaffa Merchants Association, Jaffa Grocery Committee, Jewish Food Commission and probably others.

The British first started to consider what currency should be used in 1917-18 having received proposals from the Anglo-Palestinian Bank to issue banknotes. The plan was for these notes to be backed by the UK Government with reserves held at the Bank of England but the idea was rejected partly on the grounds that supporting a Jewish institution would have been deemed a political act at a sensitive time.

In early 1924 a Currency Committee was set up to formulate a scheme for a local Palestinian currency. British officials and representatives of local banks joined the committee. The choice of base currency was between the British Pound and the French Franc, still widely used in Palestine and of course in Syria and Lebanon. The Pound prevailed.

Their next consideration was the name of the currency – one was wanted which would ideally translate well into both Arab and Hebrew. The result was a decision to create a Palestine Pound, fixed at par to the British Pound and backed by sterling currency and securities held in London. The final question was how to subdivide the new currency – into shillings and pence like the Cyprus Pound or into 1,000 mils (millièmes), like the Egyptian Pound. The mils were chosen given Egyptian money was already circulating.

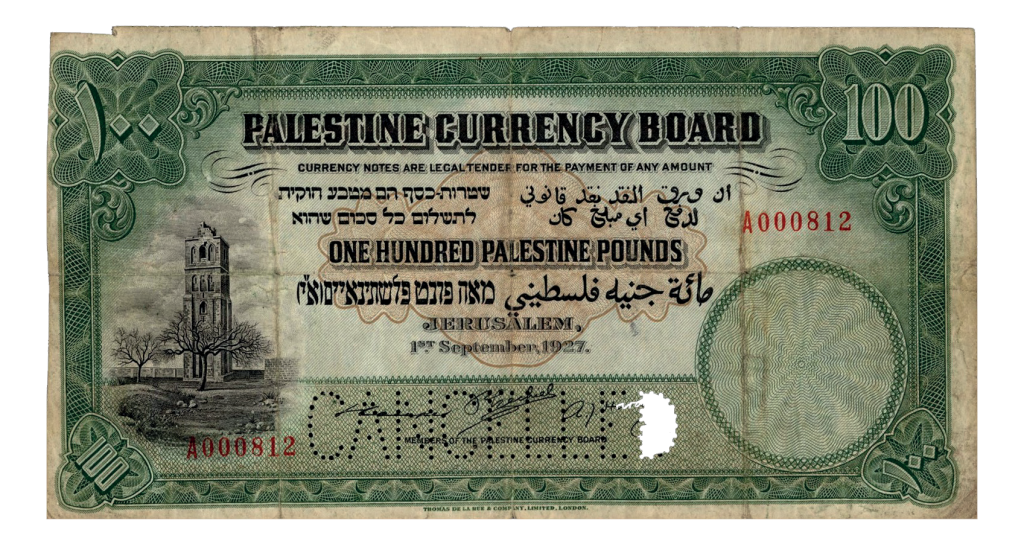

The Palestine Currency Board was established in London on 15th June 1926 and the new notes, ordered from Thomas De La Rue, entered circulation on 1st November 1927. They also circulated in the Trans-Jordan region of the mandate area but not in Iraq where a separate local currency was created. Egyptian notes remained legal tender in Palestine until 31st March 1928 while British Treasury and Bank of England notes were also legal tender.

Despite initial controversies over the designs the notes were ultimately accepted and the designs remained unchanged throughout (though much thought was given to changing some of the vignettes as surviving proofs and essays show).

The demise of the Palestine Pound

The end of Britain’s mandate led inevitably to the demise of the Palestine Currency Board and its note issues. While the Bank of England retained responsibility for redeeming all the outstanding notes the government moved to block the sterling balances backing the currency and excluded Palestine from the Sterling Zone. The transition period was thus far from straightforward and not helped by the United Nations who had first proposed the unworkable solution of a Joint Economic Board issuing a single successor currency to be used by both Israel and Palestine despite the open hostility between the two.

The UN had proposed that their Palestine Commission took over the territory’s administration but due to the growing conflict they wound it up in May 1948. De facto the newly declared State of Israel took over responsibility for the supply of currency. This was done by authorising the issue of a new notes by the Anglo-Palestine Bank. These notes had already been ordered in April 1948 before the names of either the currency or the country itself had been agreed but for a limited period were exchangeable at par for the old Palestine Pounds. They were first issued on 16th August 1948 and circulated until 1952 when notes in Israel Pounds were launched.

In the Kingdom of Jordan new notes in Jordanian Dinars were issued in 1949 while allowing the Palestine Pound to continue to circulate. It was demonetised on 30th June 1951. Jordan remained in the Sterling Zone and its currency was backed by sterling. Finally, in the Gaza strip the Egyptian Pound became the sole currency. These were also redeemable for sterling in London.

The banknotes of the Palestine Currency Board

The banknotes of Palestine have been studied in detail by numerous researchers and collectors, none more so than by Raphael Dabbah in his 2005 catalogue. This section summarises the key features of the notes and presents a chart of recorded survivors taken from the PMG population report. These will of course represent only a percentage of the total number available to the collecting market but are a useful guide to relative scarcity.

The British authorities went to great lengths to choose designs that would reflect both Islamic and Jewish traditions but ended up pleasing neither side. The designs were greeted with dismay by the Arabs who felt they had been humiliated due to poor calligraphy and grammatical errors, the poor choice of vignettes and – worst – their launch on the 10th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration.

Jews were also disappointed in that Rachel’s Tomb is not conclusively the site of her burial and thus not truly representative of the Jewish faith, and by the choice of the currency name Pound rather than their preference, the Dinar. Christians were also upset that there was no representation at all of their faith. Arab leaders initially called for the notes to be boycotted in favour of Egyptian ones but they were finally accepted by all sides and continued in circulation unchanged until their final withdrawal after the British had left.

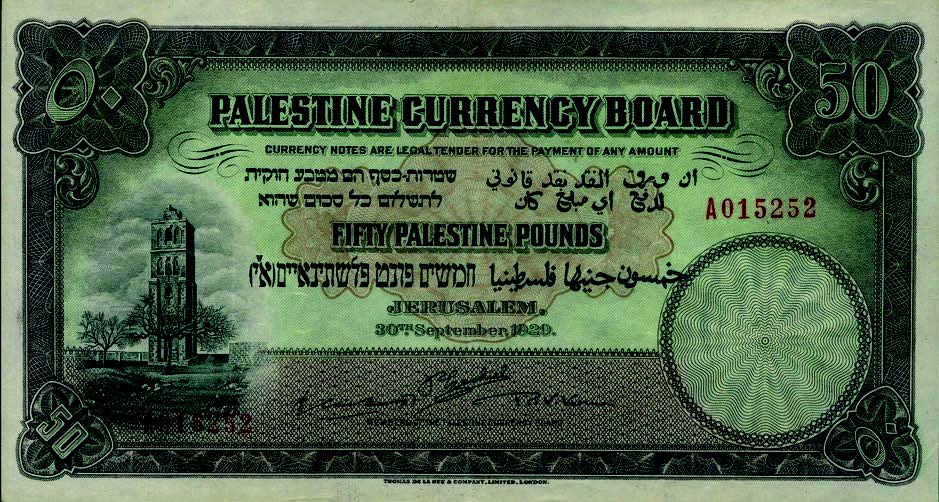

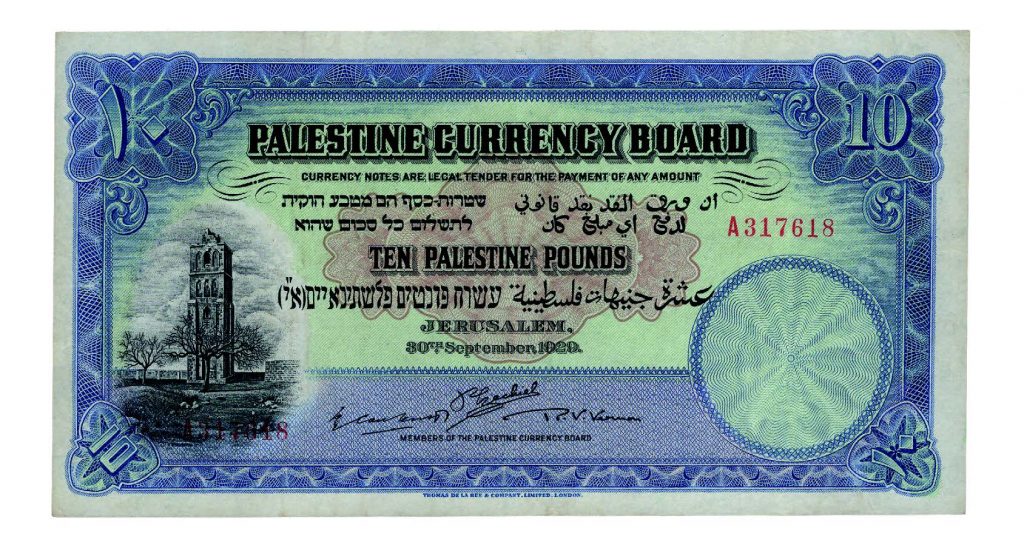

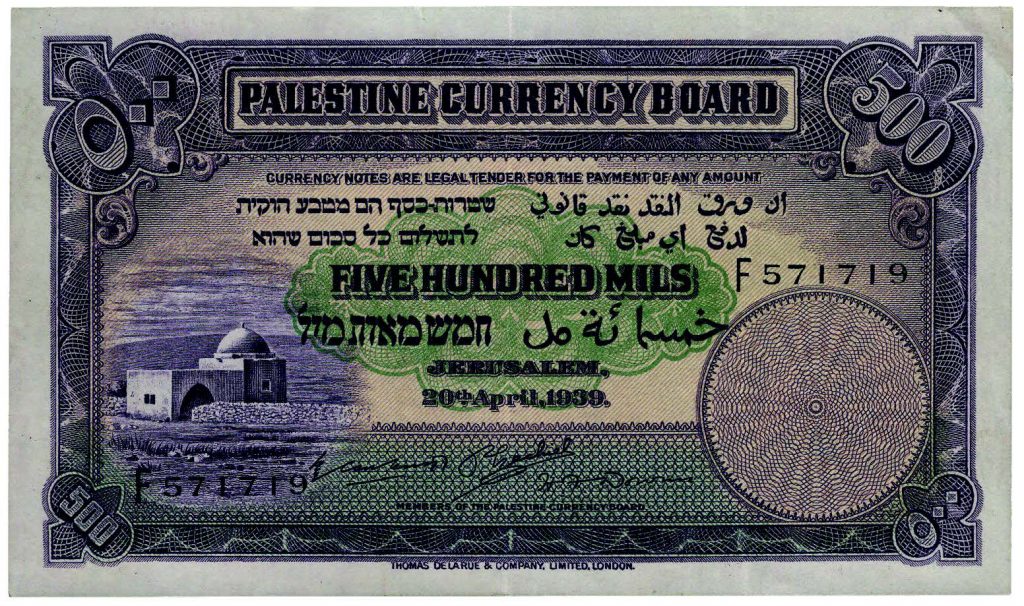

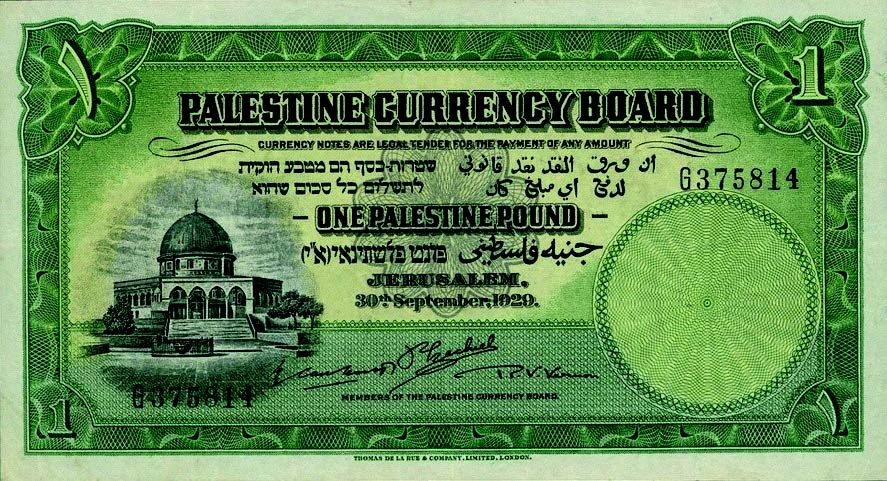

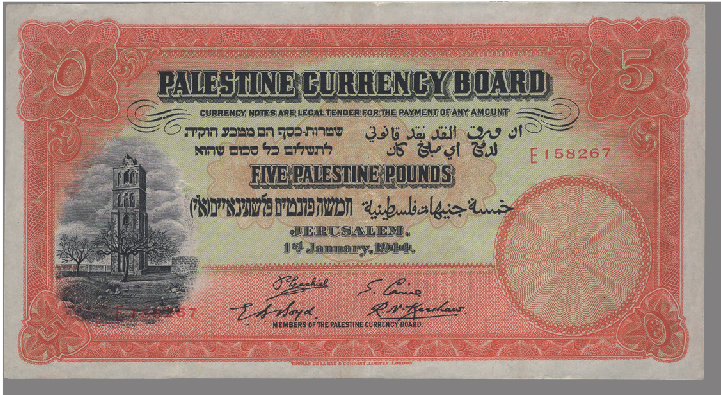

The notes carried text in the three official languages of Palestine: English, Arabic and Hebrew and stated that they were “Legal Tender for any amount”. The vignettes on the obverse of the issued notes were as follows:

500 Mils – Rachel’s tomb near Bethlehem after the 1841 renovation by Sir Moses Montefiore had added a wing on the eastern side. The structure has also functioned as a mosque.

£1 – the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount, Jerusalem, the most ancient Islamic building in the world and the third most holy site in Islam, built 685-705 AD with later modifications.

£5 to £100 – the Crusader’s or White Tower at Ramla, a 27m high minaret built in 1318.

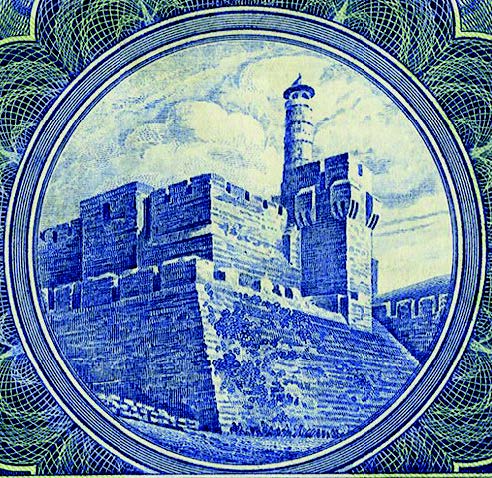

The reverses of all seven denominations featured a vignette of the Tower of David citadel in Jerusalem, including the Ottoman minaret built in the south western corner of the fortress.

A number of proofs and colour trials have survived and some feature alternative vignettes. Although none entered circulation this is a strong indication of the desire of the British authorities to assuage the concerns expressed over the original designs. Notes were prepared with vignettes of: Absolom’s Tomb, a Jewish structure dating from the 1st century AD the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian Quarter of Jerusalem a different view of the Tower of David citadel the 18th century Al-Jazzah mosque in Acre.

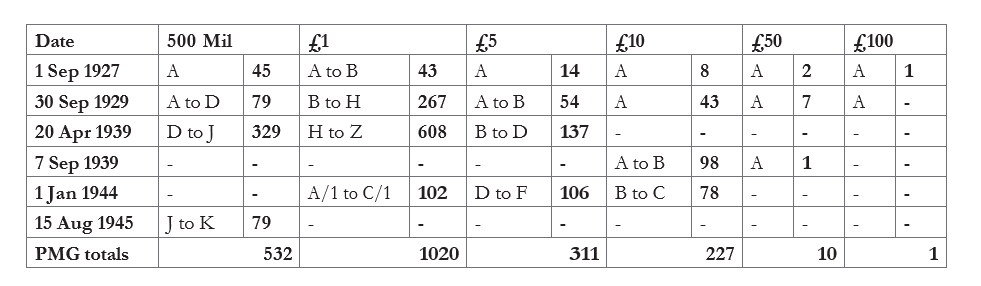

Chart of issued notes only

This chart covers only the issued notes and sets out the prefix ranges and dates alongside the PMG population report of each date.

The total of recorded survivors of the very rare £50 and £100 notes come to 22 and 9 respectively, including cancelled notes which would have been removed from the Bank of England’s record of outstanding notes: they state that 82 £50 and only 8 £100 notes remain unredeemed.

These will of course represent only a percentage of the total number available to the collecting market but are a useful guide to relative scarcity.

Recommended further reading from Jonathan Callaway

Sir Julian Crossley & John Blandford: The DCO Story (London 1975)

Raphael Dabbah: Currency Notes of the Palestine Currency Board (Jerusalem 2005) Owen Linzmayer: The Banknote Book – Palestine (2021, constantly updated)

Lt-Col Sir Richard Verdin: The Cheshire (Earl of Chester’s) Yeomanry 1898-1967 (privately published 1971) Paul Wilson: Shades of Sovereignty (London 2021)