Chris Taft

SORTING BRITAIN: THE POWER OF POSTCODES

In March 2022, The Postal Museum opened its new exhibition Sorting Britain: The Power of Postcodes. The show celebrates the story of the postcode and the huge impact it has on people’s daily lives, from the price of your house, your car insurance premium and what takeaway food is available to you, to the range of healthcare you can get. It was, however, developed in the mid-20th century merely to help sort and process the post. The exhibition addresses two key questions: Why do you have a postcode, and What does your postcode say about you?

Chris Taft, Head of Collections at The Postal Museum shares some of the key highlights of the Exhibition:

An often-asked question is simply how does the postcode work? What do all the letters and numbers mean? Is it an indication of the distance of the post office, the proximity to the town centre or some big secret code? The exhibition introduces the postcode and explains exactly how it works and what each part means. Using the Museum’s own postcode as an example and a series of maps, the exhibition breaks down the outward and inward parts of the code, showing that WC1X takes letters and parcels to the relevant local delivery office, in the Museum’s case at Mount Pleasant, and the latter inward code 0DA is used by the delivery office to sort the mail to relevant delivery round.

The modern postcode, however, has its origins much earlier. In the 1850s, London was divided down into a series of districts that are still used today, such as N, SE and EC. These districts once each had their own district offices. Displayed for the first time in the Museum are some of the early maps that show these early divisions.

The reason why locations are divided into districts – and why eventually postcodes came into being – is highlighted in the show with some examples of very early letters, some from the Museum’s own collection and some kindly loaned by a collector. The letters displayed show the variety of addresses used and perhaps give an insight into why some form of standardisation was needed in the first place.

Visitors to the exhibition will be able to try their hand at sorting post for themselves, on an original wooden sorting frame. This will give an insight into just how slow a process it could be and why as volumes of mail went up machines were trialled to try and speed up the process.

The first sorting machine used by the General Post Office (GPO) was a Dutch-made machine called the Transorma. This huge and very noisy machine was installed in Brighton in the late 1920s, and despite being heralded as the solution to all sorts of problems it never really lived up to the promise. Very little of this machine survives but on display in the exhibition will be the original manufacturer’s plate, along with the only known surviving examples of the operator’s identification keys, known as idents.

Developing new technology and researching how modern developments could help all aspects of the postal operation became an important part of what the Post Office’s research team did. In the 1920s lots of experiments were taking place and a new research centre was required, away from the noise and limited space of Central London. Dollis Hill, in North-West London, was identified as a suitable site for this new research centre. The First World War delayed the build of the new facility but eventually the main building was completed and officially opened in 1933 by the Prime Minister. The official programme from the opening is on display, alongside some of the early building plans.

While the research coming out of Dollis Hill was undoubtedly important, the people carrying this out were what made it all possible. The show celebrates just some of those people, including Dame Stephanie Shirley CH who arrived at Dollis Hill and managed to overcome many barriers, including sexism, to establish her career and be involved in work on the Premium Bond number-generating machine, known as ERNIE. The head of the research centre, Sir Gordon Radley, drove much of this change through his own enquiring mind and willingness to take risks and trial new things. Without someone like Radley much of this development may never have happened.

Working alongside Dame Stephanie and Sir Gordon at Dollis Hill was the hugely talented Tommy Flowers. Flowers was an electrical engineer working for the GPO in the Signalling and Circuit laboratory. During the Second World War his skills as an electrical engineer were requested by Alan Turing at Bletchley Park who wanted Flowers to help with developing machines to crack the German secret codes. Flowers developed Colossus, the world’s first programmable computer, at Dollis Hill and then built it at Bletchley Park to help break the codes. The technology behind the incredible machine then helped drive the development of postal machinery in the years that followed.

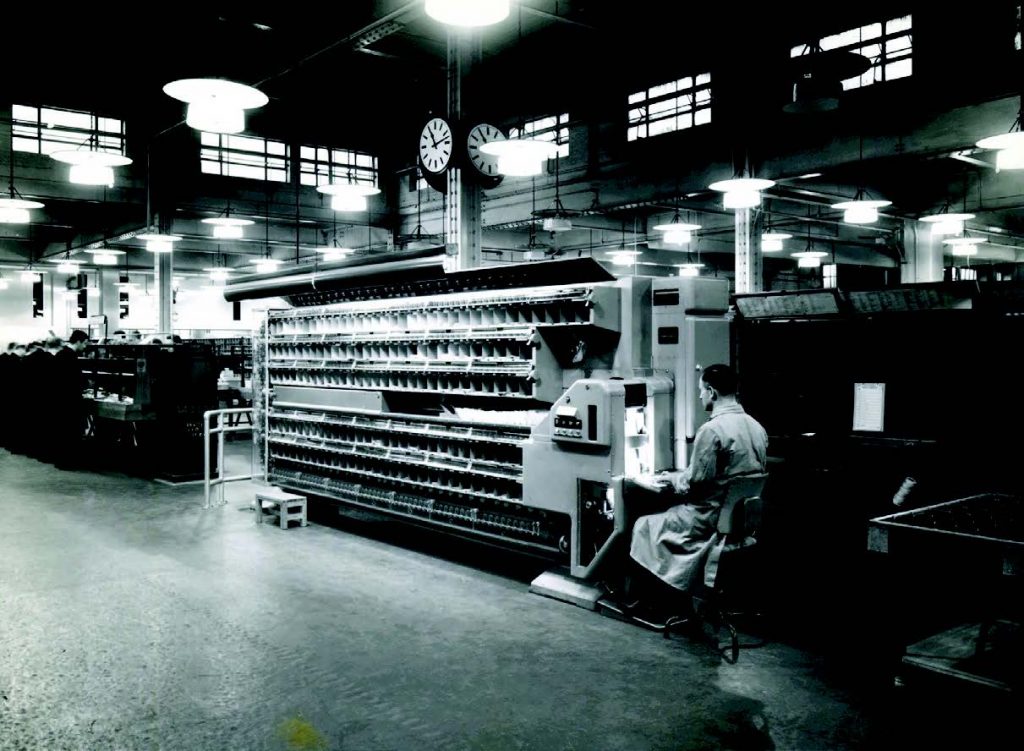

By the 1950s the scientists at Dollis Hill were turning their attention to developing their own sorting machine, to try and address some of the issues with the Dutch Transorma machine. The machine they developed was designed to be operated from a single position, becoming known as the Single Position Letter Sorting Machine, or SPLSM. Like other GPO machines being developed around that time it was given a human name, in this case ELSIE. ELSIE was to be the first successful British sorting machine and the only known surviving example is the centrepiece of the Museum’s exhibition. ELSIE is a long narrow machine with a series of pigeon-holes or boxes along one side. Letters ran on conveyor belts and were presented to an operator at one end of the machine. The operator keyed in a code that related to the destination of the letter. The machine then sorted this coded letter into the relevant box. This greatly sped up the process of sorting the mail.

On display along the machine itself are examples of items of mail that were sorted in the ELSIE machines, and examples of later letters that show how this sorting technology was to develop. As letters were coded this code was printed onto the envelopes in a series of near invisible dots. The dots, printed with phosphor, could be read by other machines to aid the sorting process and became an important part of the mechanisation story. While initially they were almost invisible to the naked eye, the post office realised that if they were more visible not only would this allow postal workers to check that codes were accurate, but visible dots on the envelopes would convince the public that machines were in use and help encourage the use of the postcode.

Machines in that period were not able to read addresses as fully as they can today; rather they had to read or be told codes. The purpose of ELSIE was to code the letters based on addresses, but it relied on postal workers memorising hundreds of different codes. Much easier, it was considered, was to ask the public to write the code on the letters themselves; this way workers could simply enter the code without need to memorise or look them up. Thus was born the postcode, or postal coding as it was more commonly known at the time.

Shown in the exhibition are examples of letters and promotional material around the trial of the postcode, which took place in Norwich, beginning in 1959. On 28th July that year the trial of postcodes was formally launched and every delivery point or address in Norwich was given a code. A lot of publicity was generated around this to encourage the public to use the new postal code.

After the success of the Norwich trial the postcode was rolled out nationally, starting next with Croydon. Over the next eight years or so every city, town and village in Britain was given its own postcode. The format trialled at Norwich changed before the national roll- out, so as well as being the first city to have a postcode, Norwich was also the last, as it was re- coded at the end of the roll-out so that its codes conformed with the new format. Promotional material was needed again in Norwich to advise people of the new codes.

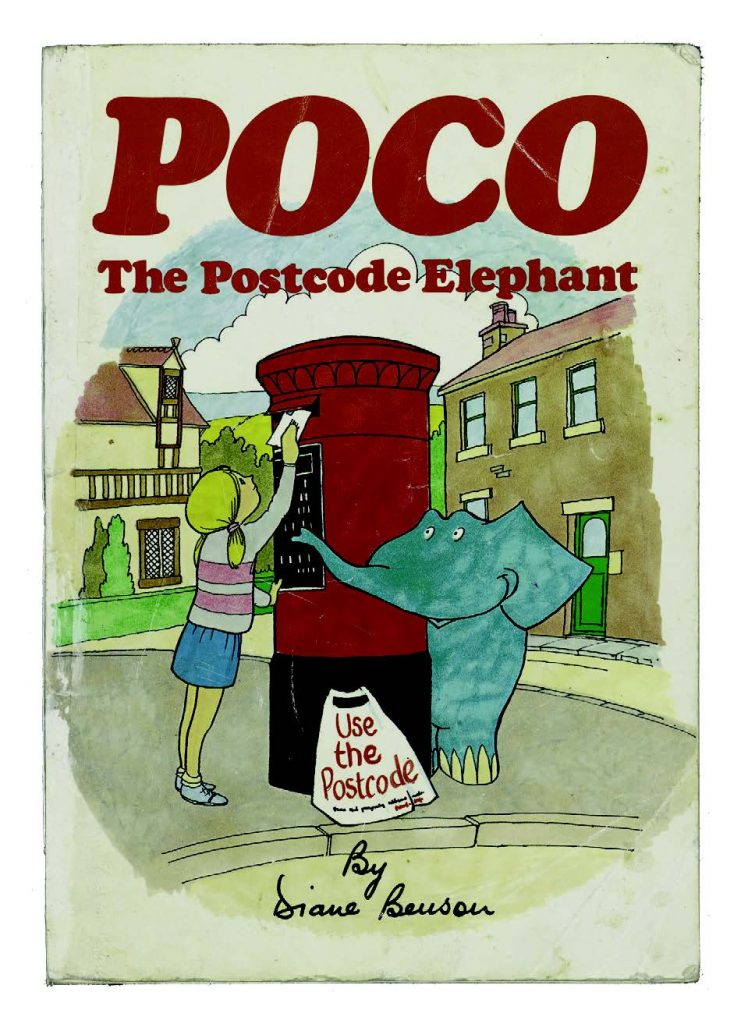

Once the whole country had postcodes allocated it became essential to promote their e so that people would always remember to use heir postcode. Leaflets, posters and advertising campaigns followed, but the biggest success came with an idea dreamt up by one of the post office’s publicity managers, Paul Diggens. He created a character that became the symbol for remembering your postcode, a pink elephant, with a knot in his trunk to help him remember his postcode. Through the late 1970s and early 1980s Poco the Postcode Elephant became a familiar character, even having its own fan club. Merchandise featuring the ephant started to appear on everything from pens and badges to portable televisions.

While the postcode was developed to simply help machines understand the destinations of letters and speed up the sorting of mail – a purely operational tool – the postcode has now become an essential part of everyday life. The exhibition concludes by exploring just some of the ways postcodes are used today. What the future holds for the development of sorting technology only time will tell, but a possible glimpse of this future can be seen in a prototype intelligent letterbox, developed by Royal Mail to experiment with just some elements that could one day become part of everyday life.

Sorting Britain: The Power of Postcodes runs until 1st January 2023 at The Postal Museum, London, www.postalmuseum.org