Regular readers of Insider, followers of our auctions and viewers of the Medal Department YouTube videos will already know that my particular interest within military history focusses on the Napoleonic Wars. Over the past few years I have been fortunate to handle, research and catalogue some astonishing medals which have revealed truly remarkable stories of ‘derring-do’ across the globe, on land and by sea, during the early nineteenth century – and Lieutenant William Pilch’s Naval General Service Medal is definitely no exception.

Lt William Pilch RN, circa 1830

Named around the edge in the usual style to ‘William Pilch, Volr. 1st Class’ and bearing two clasps – ‘Trafalgar’ and ‘Northumberland 22 May 1812’ – it is a unique combination to a naval veteran for the Napoleonic Wars. This is his story.

William Pilch was born on 21st April 1794 to William and Margaret Pilch of Burnham Market, Norfolk. Baptised six days later, most interestingly the rector of the parish was The Reverend Edmund Nelson, father of none other than Horatio Nelson, who at that time was making a name for himself at the Invasion of Corsica. By family repute, the friendship between the families of Nelson and Pilch led to young William entering the Royal Navy on 4th October 1804 – at the tender age of 10 – as a First Class Volunteer aboard HMS Bellerophon, a 74- gun ship-of-the-line affectionately known in the service as the “Billy Ruffian”. She served with much distinction in three major fleet actions (the Glorious First of June, the Nile and Trafalgar), in addition to a host of smaller engagements throughout her 50-year career, but it is of course on that fateful day of 21st October 1805 that she played a prominent part in one of history’s most famous battles – along with the 11-year-old William Pilch.

“To be in a general engagement with Nelson would crown all my military ambition”

Cooke, John (1763-1805), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Under the command of Captain John Cooke (a long-serving and well-respected officer), Bellerophon was fifth in Vice-Admiral Collingwood’s lee column (astern of Tonnant and ahead of Achille and Colossus) and therefore one of the first ships into action with the combined Franco-Spanish fleet. As a junior member of the Midshipman’s Berth, Pilch would likely have had a small supervisory role during the battle, perhaps overseeing a section of cannon on one of the gundecks or acting as Aide-de-Camp to a more senior officer; by coincidence, another young member of the ships’ company at this time was the Signal Midshipman, John Franklin the very same man who later made his name as an explorer and lost his life on the Northwest Passage expedition of 1845. Undoubtedly Pilch and Franklin would have known each other and perhaps they exchanged a few words together when Franklin noted Nelson’s famous signal, “England Expects That Every Man Will Do His Duty”.

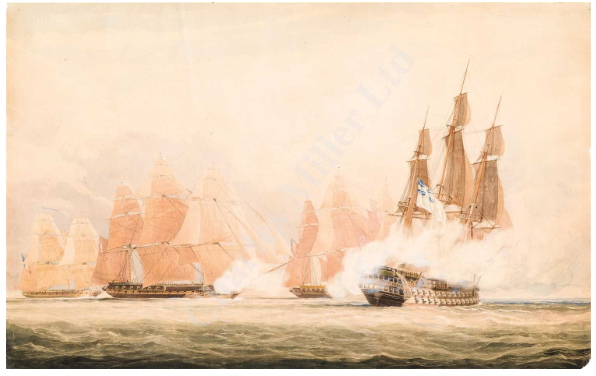

Thomas Whitcomb (British, 1763 -1824) Situation of the Bellerophon at the moment of the death of her gallant commander Captain Cooke, Aquatint on paper

At 12.30pm Bellerophon cut through the enemy line, firing two broadsides in quick succession into the Spanish 74-gun Monarca – effectively taking her out of the enemy line, such was the devastation caused by Cooke’s well-trained crew. However, a dangerous situation developed when Bellerophon next collided with the French 74- gun Aigle – their yards became entangled, locking them together in a one-on-one duel which swiftly became extremely deadly: Aigle was well commanded and the soldiers and marines on her upper deck and tops began a well-directed fire on their British opponent, concentrating especially on Bellerophon’s quarterdeck. Cooke’s first lieutenant, William Pryce Cumby, suggested to his captain that he should remove his epaulettes to make him less conspicuous a target (much like Hardy said to Nelson) but Cooke replied, “It is too late to take them off. I see my situation, but I will die like a man”.

As the duel raged, and with the British vessel also coming under fire from further French and Spanish ships, the captain of the Aigle ordered his men to board the Bellerophon and attempt to capture her. Cooke sent Cumby below to ensure her heavy guns kept firing, then personally led a counter-attack to repel the French boarders which resulted in a fierce hand-to-hand fight. At 1.11pm Cooke fell, mortally wounded, with an eyewitness statement from one of his officers providing further detail:

“He had discharged his pistols very frequently at the enemy, who as often attempted to board, and he had killed a French officer on his own quarterdeck. He was in the act of reloading his pistols… when he received two musket-balls in the breast. He immediately fell, and upon the quartermaster going up and asking him if he should take him down below, his answer was “No, let me lie quietly one minute. Tell Lieutenant Cumby never to strike”.

Letter of an officer of Bellerophon”. (2 December 1805). Printed in “a Portsmouth newspaper”, Cordingly, Billy Ruffian. p. 195.

One can only imagine what William Pilch – a mere 11 years old – was thinking and feeling at this terrifying time.

The fighting between the two ships raged for another half-hour before, finally, Aigle sheered away and attempted to flee – the “Billy Ruffian” had emerged victorious. Now under the command of Lieutenant Cumby, his exhausted crew started making repairs whilst also sending a prize crew to take possession of the Monarca, which had surrendered in the meantime; the same fate befell the 74-gun Bahama. The ‘Butcher’s Bill’ aboard Bellerophon was terrible: in addition to Captain Cooke she suffered 26 killed and 123 wounded – 30% of the ships’ company and the second-highest casualty list of the whole Lee Division: Pilch was lucky to come through completely unscathed. Though many were honoured for the part they played that historic day, young Pilch had to wait a little longer – in a Royal Navy where patronage still meant a great deal, the death of Admiral Lord Nelson likely did not do his career any favours. He is next noted, still as a Volunteer 1st Class, aboard HMS Glory until July 1806, when he was appointed in swift succession to the 64-gun ships Sampson and Diadem; in the latter he saw further active service in the controversial campaign to capture Monte Video, and whilst aboard her was finally promoted Midshipman.

Upon his return from South America Pilch was appointed to the 74-gun HMS Defiance, another Lee-column veteran of Trafalgar, and saw action in her at the Battle of Les Sables-d’Olonne (23rd February 1809), which took place off the town of the same name on the Biscay coast. During this engagement Defiance, under the command of Captain Henry Hotham, was first in line to attack three French 40-gun frigates anchored under protection of shore-based artillery batteries; due to her unusually shallow draught, Defiance was able to sail closer inshore than the remainder of the British squadron and fought alone for 20 minutes against the French vessels and gun batteries, until the remaining British ships could support her. Hugely outnumbered in men and guns, all three French frigates became so badly damaged that, unmanageable, they drifted ashore and became wrecked. Defiance had suffered casualties of two killed and 25 wounded: a small price to pay, perhaps, but the most of any ship in the British squadron.

The Action of 22nd May 1812

Nicolas Pocock (British, 1740 – 1821), The engagement between H.M.S. ‘Northumberland’ and a French squadron, Watercolour on wove paper

September 1810 found Pilch appointed – still as Midshipman – to HMS Northumberland, another 74-gun ship-of-the-line in service in home waters. After an uneventful few years, on 22nd May 1812 Northumberland was on patrol when she sighted a small French squadron of two 40- gun frigates and a 16-gun brig returning home from a raiding cruise in the Atlantic; though technically superior in numbers and guns, the French vessels opted to avoid confrontation and to reach shelter by means of a shallower stretch of coastline where the smaller ships could go but the larger and heavier battleship could not.

Unfortunately for the French, the only officer in the squadron who knew the area well enough to be certain of navigating the shoals was killed in one of Northumberland’s first broadsides; the inevitable happened and all three either hit reefs or grounded on sandbanks – the guns of Northumberland bombarded their enemy from a suitable distance, with both frigates eventually catching fire and exploding, only the brig Mameluck being refloated and saved the following day. The battle had not been an entirely one-sided affair however, with casualties aboard Northumberland being some 33 killed and wounded and damage to her masts and rigging.

Next appointed to HMS Valiant, another 74-gun ship, Pilch found himself heading further afield for the first time in several years – specifically to the North American station, where a much enlarged naval presence was required to combat their new foe in the War of 1812. Intriguingly, having served with Captain Henry Hotham aboard Northumberland for the engagement in May 1812, Pilch’s ‘Memorandum of Services’ notes that every subsequent ship he was appointed to (San Domingo, Asia, Tonnant, Forth and Superb) was either directly or indirectly commanded by Hotham: did Pilch make such a good impression upon his senior that he secured some patronage and active employment in these later years? The 80-gun Tonnant acted as flagship for the Chesapeake and New Orleans campaigns and the 74-gun Superb participated in the attack upon Wareham in Massachusetts, and whilst on this station (24th September 1814) Pilch was finally – and most deservedly – promoted Lieutenant.

A Naval Knight of Windsor

‘Turned ashore’ at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Pilch is next noted as entering the Coastguard Service on 28th February 1827 regular employment must have been keenly appreciated after many years on a Lieutenant’s half-pay salary. By 1841 the census of that year describes him as ‘Lieutenant RN’ and resident of the Coast Station in the parish of St Peter’s, Broadstairs, Kent and six years later he is further noted as the ‘Chief Officer’. After 20 years with the Coastguard, Pilch was appointed a Naval Knight of Windsor – a rare honour indeed which brought with it an annual salary of £100-6-0 per annum.

Unlike the Military Knights of Windsor (which exist to this day) the Naval Knights are a little-known body of men which only existed officially from 1797-1892 and during that time only 59 were ever appointed. Their qualifications for the position included having to be a Lieutenant upon retirement from the Navy, to be single without children, and of good and sober repute. In a further difference from the Military Knights, their Senior Service colleagues did not have accommodation within the walls of Windsor Castle itself, rather inhabiting a purpose-built property in the town comprising houses and a mess-room, joined by a colonnade and topped with a clocktower and cupola. The duties of a Naval Knight were not onerous, appearing to mostly consist of wearing their Full-Dress uniforms and regularly attending services at St George’s Chapel, while being “inclined to lead a virtuous, studious and devout life”. It is perhaps whilst at Windsor that Pilch applied for, and received, his two-clasp Naval General Service Medal as record of an adventurous life at sea.

After 15 years’ as a Naval Knight, William Pilch died – aged 70 – at Broadstairs, and is buried at the church of St Peter-in-Thanet in the centre of the town. A life-long bachelor, Pilch’s Grant of Probate left his effects (totalling just under £600) to a sister, Susan Youngs of Titchwell, Norfolk – a village not far from where he and his siblings were born.

Postscript

By a strange quirk of fate – and though Pilch himself was aboard neither vessel at the time – both Bellerophon and Northumberland had the honour of receiving the ex-Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte upon his surrender in July 1815.

Lieutenant William Pilch’s Naval General Service Medal will be offered for sale by Spink London as Lot 3 of our Orders, Decorations and Medals auction, on 4th April 2023, with an estimate of £12,000 – £15,000.