“Hidden in the lines of these meticulously detailed inventories we find the story of a seventeenth century woman with a passion for collecting”

On 25th November 1715 a letter, sent from the Royal Household, was received by all governors and county governors of the Swedish Kingdom. Mass was can-celled, ecclesiastical interiors were to be covered in swathes of dark cloth and all male subjects were instructed to don outfits of black. Hedwig Eleonora, the dowager Queen of Sweden, had died at the age of 79. Word of the dowager queen’s death spread rapidly throughout the lands, yet her funeral would not be held until January 1717, some thirteen months after her passing.

Toussaint Gelton, Queen Hedvig Eleonora, c. 1663-1673. Oil on canvas. Finland, Finnish National Gallery

In the intervening months, the kingdom was placed in a state of national mourning, and behind palace walls, officials were left with the task of piecing together the remains of the deceased queen’s life. Hidden in the lines of these meticulously detailed inventories we find the story of a seventeenth century woman with a passion for collecting. But more so, we come to understand the intertwinement of collecting and identity, and how a particular set of circumstances enabled a woman to use her cultural interests to challenge the restrictions enforced upon her.

Born to Frederick III, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein (1597-1659) and his wife, Maria Elisabeth, the Princess of Saxony (1610-84) in October 1636, Hedwig Eleonora was the sixth of her parents’ sixteen children. Precisely one day after her eighteenth birthday, she was married to King Charles X Gustav of Sweden and crowned queen at Stockholm Cathedral. But, after only six years of marriage, she was widowed in 1660 and left with a young infant, the future King Charles XI. The now dowager queen assumed the role of Regent to the state; a position of limited political control, shared with the Regency Council. More significantly, however, were the stipulations of her marriage contract: the young queen was entitled to a ‘widow’s life-rent’. The sprawling estates were no longer under the name of her ‘superior’ husband, but her own – they were entirely hers, hers to throw parties in (of which there were many), hers to play dress-up in (which she did frequently) and hers to gamble in (which she did into the night, apparently). But perhaps most importantly, these impressive architectural structures, through taxes and benefits, enabled Hedwig Eleonora access to her own private income. It was, however morbid it may sound, the untimely death of her husband, and the fact that she had already fulfilled her patrilineal duty to produce a suitable heir, that gave the dowager queen complete autonomy in her intellectual interests and cultural pursuits. Had the young queen borne a child every year (as was both her womanly and godly duty), she simply would not have had the opportunity to commission the palaces of Strömsholm and Drottningholm, or to rebuild and renovate the palaces of Karlberg and Ulriksdal – let alone pursue her collecting endeavours.

A short boat ride from Stockholm, at the very end of an enfilade of state apartments of Ulriksdal Palace, we come across a small room with a small door. We fumble for the key, and turn it slowly in its lock. What we find are seven cabinets, standing modestly in an otherwise empty room. One glance over our shoulder, to make sure we are really, truly alone, and then we cast our greedy eyes to the shelves: sparkling technicolour jewels; baroque pearls made to look like monsters; mounted rock crystals; miniature portraits; tortoiseshells; daggers and knives; turned ivories; a ring set with a bezoar stone; sugared lumps of amber; and the pièce de résistance – a unicorn horn so large that it is forced to rest, solitary, in a corner, its pointed tip reaching towards the ceiling. In total, these pretiosa cabinets held around 173 objects. Each curiosity was matched with its own label, and arranged in a systematic manner by material.

Anonymous, Finger ring with bezoar stone belonging to the Queen of Sweden,

seventeenth century. Stockholm, Livrustkammaren (The Royal Academy) Museum

What do these seven cabinets, and their varied inhabitants, tell us about the dowager queen? Their positioning in the palace, in a room hidden away from the ‘official royal space’ suggests that this collection was never assembled with the intention for public viewing. A letter sent in 1709 to Matthias Hogman, the freshly appointed steward of the Ulriksdal Palace, indicates the duty of care expected from the dowager queen:

“. . . all the furnishings and interiors, [which are to have] frequent inspection and careful watch . . . [that] all cabinets and rooms large and small, should always be clean and tidy . . . [and] in her Majesty’s absence, the house and its rooms shall be kept properly and shut . . . Her Majesty allows that when some of good character or other curious and appropriate people should ask to see the house and its apartments, the palace steward should give them access…”

There is a sense of unreachability to these objects – the objects themselves span across Europe, into the furthest corners of the world and then back again, housed in seven individual cabinets in a dark room in a palace in Sweden. But these objects are also unreachable because their owner made them so. Through limiting access, the dowager queen increased their exclusivity, adding a further dimension to the material wealth present in the room.

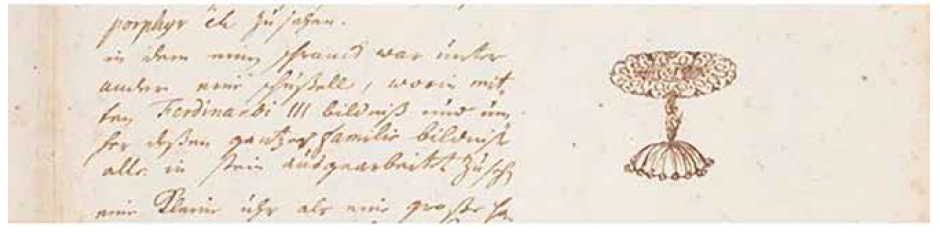

In fact, we have just one record of a visitor, in 1697. The visitor, in her diary that evening, heralded the ‘artfully worked things of amber, ivory, jasper, porphyry’, and seemed particularly taken with a large tazza dish, that included a coral cameo portrait of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III mounted in its centre.

Anonymous, African knife with bone haft and wooden sheath, seventeenth century. Stockholm, Etnografiska Museet

Thought to have been war booty acquired from the courts of Munich or Prague, the dish is interesting for it was both the most highly valued piece of the collection, but it also reminds the viewer of the dynastic nature of the collection as a whole – it is Hedwig Eleonora’s status as queen that allows her hand to reach for these wondrous objects from afar, to graciously receive them as gifts or bid for them in auction, or, as in this case, acquire them from a pile of looted goods in the aftermath of a war. The light of her predecessor, Queen Christina of Sweden, shone so bright in the academic world that it saw Hedwig Eleonora cast in a shadow. There exist just two complete books on Hedwig Eleonora: a novel written by Nanna Lundh-Ericsson, published in 1947, and a more recent 2017 study by Lisa Skough. Her pretiosa collection tells us something about the queen’s fascination with a world that existed beyond European boarders. Freed from the tight constraints of early modern marriage and motherhood, the queen sought to minimise this world, harness it and keep it in a series of

objects intended for solitary viewing and curious eyes. Yet, at the centre of this collection lies a complex question of the interrelation of power, colonialism and art. The modern museum continues to grapple (and repeatedly fail) to answer such a question, and as such, we must ask ourselves what can be learned from the pretiosa collections like that of Hedwig Eleonora, and what role they play in the re-envisioning of the Western Museum.

Latest Comments

Right here is the perfect blog for anybody who wishes to find out about this topic. You know a whole…

Thanks for your blog, nice to read. Do not stop.

Right here is the perfect blog for anybody who wishes to find out about this topic. You know a whole lot it’s almost hard to argue with you. You certainly put a new spin on a subject that has been written about for decades. Excellent stuff, just excellent!