Sam Moorhead

“Carausius, in particular, had a vast output of different designs and inscriptions which give many indications as to his character and aspects of his reign”

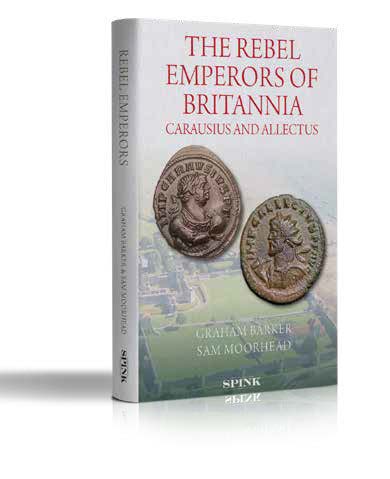

Carausius and Allectus may be well-known to certain coin collectors, museum curators and coin dealers but they remain largely unknown to most people. At the end of third century AD, these two men successively ruled Britain, and parts of the Continental coast, as rebel emperors for a period of ten years. They minted their own coins, initiated Britain’s first truly integrated defence system and successfully repelled an invasion from the mighty Roman empire. These are extraordinary achievements by any standards.

Our new book, published in April by Spink Books, will aim to tell the incredible story of these two rebel emperors. While elements of the story remain speculative, enough evidence remains to piece together this exciting episode in the history of Britain. The book will look at how the Romans regarded Britannia from the outset and why the secessionist empire posed such a huge threat to the authority of Diocletian and Maximian. The book looks not only at how Carausius set up his rebel empire but examines the people who lived there, the gods that inspired the rebel emperors and the key towns and cities in Britain that Carausius and Allectus would have known.

Denarius of Carausius with reverse of war galley and inscription FELICITA AVG: good fortune of the emperor, RIC V.5, no.87 (private collection)

The main physical evidence for their existence is the considerable range and variety of coinage. Carausius, in particular, had a vast output of different designs and inscriptions which give many indications as to his character and aspects of his reign. Two Roman historians from the mid-4th century AD record key details, in a dispassionate way, about Carausius and Allectus. Eutropius was an official at the court of the emperor Valens (AD 364 – 378) and he wrote A short history of the Roman Empire (Breviarum Historiae Romanae) in around AD 369. Aurelius Victor was a politician and writer of roughly the same period who published his Brief summary of the reigns of Roman Emperors (Epitome de Caesaribus) in around AD 361. Later references to the rebel emperors include Bede’s writings in the 8th century AD and the history of Zonaras in the 12th century AD.

Perhaps the most extraordinary documents to survive from the late 3rd and 4th century are the Imperial Court Speeches known as panegyrics. These Court Speeches were an elaborate exercise in ‘praising to the skies’ the emperor of the day and were extremely biased. Great care needs to be taken when interpreting them. Nevertheless, the Court Speeches provide some of the only surviving contemporary details of this period of history. The actual names of Carausius and Allectus are never used in these orations; they are only referred to as pirates or criminals. Allectus is simply referred to as the ‘henchman’ of the archpirate. Although Carausius was a usurper, he modelled himself as a conventional Roman emperor, giving himself all the imperial titles. Uniquely, he quoted the Roman poet Virgil on his coins to bolster his claims of legitimation. A rare brass medallion of Carausius, now in the British Museum, carries an image of a winged Victory in a chariot drawn by two horses and a standard inscription of ‘Victory of the Emperor Carausius’ (VICTORIA CARAVSI AVG). Across the lower part of the medallion (exergue) is a series of letters, INPCDA, which remained a mystery for many years. In 1998, Guy de la Bédoyère realised that these letters correlate to the initial letters of a line of verse written Virgil in around 40 BC. In his messianic fourth Eclogue there is a line which reads: Iam Nova Progenies Caelo Demittitur Alto. This translates as ‘Now a new generation descends from high Heaven’. The three-word phrase preceding this line is Redeunt Saturnia Regna which translates as ‘The Golden Age Returns’.

Fig. 5.2. Silver denarius of Carausius with EXPECTATE VENIES / ‘Come, long awaited One’ on the reverse and the initials RSR standing for Redeunt Saturnia Regna (The Golden Age Returns); RIC V.5, no. 72 (private collection)

The majority of the silver coinage (Figure 5.2), and some gold and bronze coins, of Carausius carry the initials RSR and Guy de la Bédoyère was the first to realise that Carausius was deliberately proclaiming the return of a Golden Age. Coins were issued proclaiming that Carausius was “long awaited” with a phrase that is also thought to derive from the writings of Virgil – expectate venies; this phrase being found in Virgil’s Aeneid (Book II, line 283). This message deftly fits with the prophetic nature of the claim in the Golden Age myth foretelling the appearance of the ‘heaven sent’ emperor. Carausius also devoted time and resources into bolstering his coastal defences, strengthening the forts of what later became known as the Saxon Shore. It is likely that he added new forts, with Portchester (Portus Adurni), on the Solent, being the best example. He also fortified parts of the west coast, for example with a fort at Lancaster, and it seems likely that he secured a peaceful northern frontier through a treaty with the Picts.

It is now clear that that the emperor Maximian mounted a much vaunted, fullscale invasion in AD 289. This, however, was successfully repelled by Carausius to the deep humiliation of Diocletian and Maximian. What followed is interesting. It seems that Diocletian and Maximian adopted the policy of keeping their enemy close and it appears that Carausius was, on the face of it, accepted as a co-emperor. It was deniable peace. Although Diocletian and Maximian do not strike coins for Carausius, he strikes them in abundance for his continental colleagues, even in gold. The most famous of these coins shows the busts of all three emperors on the obverse with the legend CARAVSIVS ET FRATRES SVI (‘Carausius and his brothers’).

Radiate coin of Carausius with portraits of the three emperors and the inscription ‘Carausius and his

Brothers,’ RIC V.5, no. 3526 (private collection)

A very rare coin issue also shows Diocletian shaking hands with Carausius with Maximian looking on with the inscription CONCORDIA AVG (harmony of the Augusti). However, Diocletian and Maximian were just biding their time until another and more powerful invasion could be mounted. In AD 293 Constantius Chlorus was promoted to be the junior emperor under Maximian, with the explicit task of dealing with Carausius.

Rare radiate coin of Carausius, issued in Diocletian’s name proclaiming the agreement of 3 emperors:

Carausius, on the left, shakes hands with Diocletian while Maximian looks on. (RIC V.5, no. 3597; Private collection)

The official Roman sources claim that a senior officer in Carausius’ administration called Allectus assassinated his master. Allectus may either have been Chief Finance Officer or possibly Praetorian Prefect. Whether or not Allectus had a hand in the death of Carausius, he certainly succeeded him. Allectus continued the building programme and started monumental structures in London, on the north bank of the Thames near the Millennium Bridge Here, he seems to have intended to construct two new temples. Allectus also added the colossal shore fort at Pevensey to the coastal defences of Britannia.

(Photo: Commission Air © G Barker and

S Moorhead)

However, his London plans were never realised because in 295 or 296 the emperor Constantius made his final moves. Firstly, Boulogne was captured and then two invasion fleets sailed to Britain. The first, under the command of Asclepiodotus, evaded the British fleet in the Solent due to fog off the Isle of Wight. The invaders landed and defeated an army led by Allectus, probably somewhere on the South Downs. The army of Asclepiodotus went on to take London where much blood was spilt. Constantius and his army eventually sailed up the Thames and then claimed all the credit. The Court Speeches tell us, quite improbably, that the Britons were delirious with delight to catch sight of Constantius – the man who restored them to the Eternal Light of Rome.

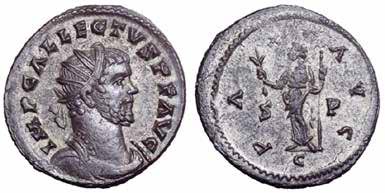

Radiate of Allectus with ‘Peace of the Emperor’ (Pax Avg) on the reverse,

RIC V.5, no. 394 (private collection)

Despite Court Speeches telling us of the clemency and benevolence of Constantius, the treatment meted out to remnants of the rebel regime was brutal. There were public executions in amphitheatres, confiscation of property and forced resettlement. A milestone, near Carlisle, inscribed with Carausius’s name was upended and a later emperor’s name inscribed on it. Coin hoards show us that coins of Carausius and Allectus were carefully removed from circulation. In fact, a deliberate attempt was made to wipe the rebel emperors from history. Their name and memory did survive, however. Rare, crude coins from the fourth century are known to have carried the name of another Carausius. Furthermore, a Dark Age tombstone from Penmachno in Wales shows that his name survived into the mediaeval period.

In later history, the printed books on Roman coins of the 16th and 17th centuries featured coins of Carausius and Allectus and the 18th century saw the feverish adulation of Carausius as he was rediscovered as a lost British naval hero. Books devoted solely to the rebel emperors of Britannia were published by Claude Genebrier in France (1740) and also by William Stukeley in Britain (1757). Their coins started to fetch enormous prices at auction and any antiquarian worth their salt had to have coins of Carausius and Allectus in their collection. The obsession with Carausius can even be read in Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776) when the dubious claim was made for Carausius that: “Under his command, Britain, destined in a future age to obtain the empire of the sea, already assumed its natural and respectable station of a maritime power.”

After this frenzy of attention in the 18th century, Carausius and Allectus quietly faded from view surfacing only occasionally in various fictionalised accounts and in coin catalogues. Their story deserves to be better known and this book aims to set the record straight and details the remarkable achievements of these rebel emperors of Britannia.

Rebel Emperors of Britannia: Carausius and Allectus will be published by Spink Books in April. For further information please email [email protected], or visit our website (www. spinkbooks.com) to purchase a copy once available.