When a notaphilist is asked what makes an excellent banknote collection, a plethora of answers may be formulated. Some may say it is the value, be it either face or what price is realised at auction. Others

may suggest the size of the collection and how many different notes it holds. Furthermore, a collector may wish to focus on one specific era or region and attempt to garner as much material as they can from that given time period. The rise of these collections may be fuelled from a keen interest into the history of a region, with such a passion usually intrinsic to the collector. And it is the historical value which can in turn pave the way for another form of significance. For no matter how much authenticity can be replicated from a contemporary collection, there is something sensational in one that takes this historical relevance one step further.

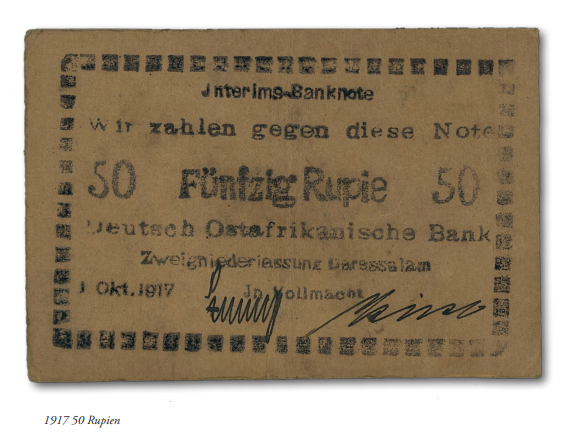

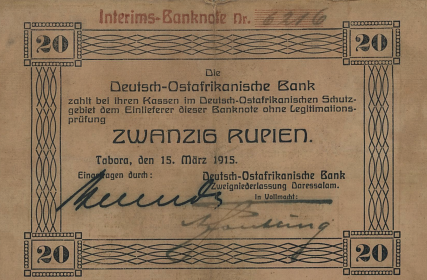

This specific collection is comprised of banknotes from German East Africa, which had its origins in 1885 when it was established as a protectorate, during the relatively short period of German colonisation. Full control of the region was implemented by the German government in 1891, culminating in the colony of German East Africa being proclaimed in 1897. With the colony under threat from British forces during WWI, the colonial Government chose to produce interim war notes. The German East African Rupie already had pre-existing silver coins circulating in the colony; however, these began to be hoarded for their use in commercial transactions. The new notes of the German East African Rupie began life with the 20 Rupien note, first issued on 15th March 1915. This was shortly followed by versions of the 1, 5, 10, 50 and 200 Rupien note, all of which were printed with an incredibly high range of varieties over the next two years. The events of WWI led to the steady demise of the German Empire. With Germany surrendering at the end of the war, the decision as to which nation should resume control of the land was determined at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. It resulted in the majority of the colony becoming British territory, meaning that an unbroken chain of British-occupied land now stretched North to South along the entirety of the African mainland.

Why so many of these notes have now come to light can be attributed to the actions of one man, who gathered the collection whilst living in the region during WWI and subsequently in the following decades. A complete explanation of how the collection came to be may sadly be lost to history, but an account from his granddaughter aids the construction of this story. Speaking over the phone, she delivered an insightful narrative that had been passed over from her family. The gentleman in question arrived in German East Africa from Western India.(part of the present-day Indian state of Gujarat), where he served with the British Army during WWI. Following the end of the war, he chose to remain in the region. Alongside other members of his family who had moved from India, the man took up residence within the British territory of Tanganyika, which had formerly made up the majority of the German East African landmass. Shortly after fathering a son in 1940, he and the family moved to the British protectorate of Uganda, where his son was raised. Here, they began a successful shop business, becoming well-known in the local area as a family of shopkeepers. It is safe to assume that by this time the banknote collection had fully accumulated and had accompanied the man on his journey to the country.

However, despite their relative prosperity, the family soon became victims of Uganda’s new military dictatorship. Full independence from British rule in the country had been achieved in 1963. By 1972, as British passport holders, they had no choice but to leave the country, due to the expulsion of ethnic Asians by Ugandan President Idi Amin. As a result, they completely migrated to Britain. It is believed that the man had left on his own prior to the ordering of the expulsion in August, possibly fearing that such an event could occur. Left with a deadline to exit Uganda in November, the family were reunited with him in Britain, albeit with extremely few belongings. But one group of items that had made their way to Britain was the banknotes, now the only physical reminder of his military past. It is still unclear why so many notes were kept from this period, although the notion of personal value is one theory from his granddaughter. She proudly described the notes as her “family’s heritage,” and likes to imagine that they were kept as a personal reminder of his time spent as a soldier. Nevertheless, it remains miraculous that he was able to keep this collection all of his life. Within the vast collection, he had gathered almost all known varieties of the interim war issues. Signature varieties, subtle differences in design, wording and font sizes are all accounted for. But one of the most striking differences that can be identified are the range of colours and materials used. The 5 Rupien note can be found in shades of blue and green, and like many of the emergency notes, was often printed on cardboard. One variety of a 1916 1 Rupie note was printed on translucent ammunition paper, with the scent of gunpowder still present today. This makes the banknote an unconventional example in which by looking at it on a solid background, both the obverse and reverse can be seen simultaneously.

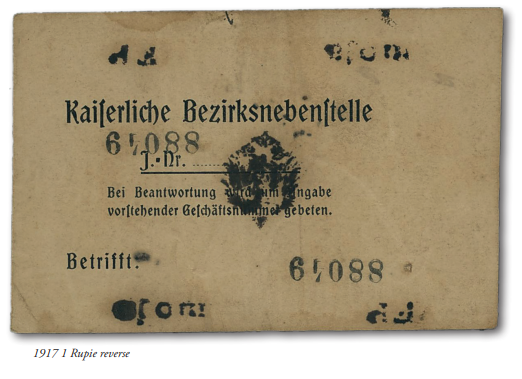

Some of the extremely minor details, such as those on the reverse of 1917 1 Rupie notes, are especially desirable to collectors. There is even an early run of a 20 Rupien note printed on linen, thereby exemplifying how quickly the notes needed to be issued. Additionally, the collection beheld some exclusively rare individual pieces. Uncovered recently were four 50 Rupien notes dated from October 1917. Very few examples of this note are known to have emerged, meaning that for generations, the man’s family had been sitting upon some of the most sought-after notes from the era. For a collection with as much historical significance as this one to include some true treasures like these, it is enough to wonder how often such a trove of banknotes is discovered – for German East African notes, perhaps just once this century? Doubtless there will be few other, if any, collections of German East Africa banknotes that could ever rival this, insofar as being one which is a truly authentic remnant of a historical period, complete with the accolade of being gathered by an individual who experienced it first-hand.