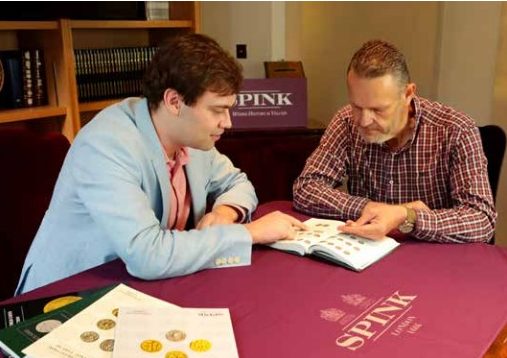

I will always remember the moment when I opened an email from Spink coin specialist Gregory Edmund, and learnt that a gold coin of King Henry III from 1257 or 1258 had been dug up by a metal detector in a field near Hemyock in Devon. A few days later I visited Spink and was shown the coin. Although slightly bent it was in good condition and unquestionably genuine.

There were several reasons for excitement. The first was that my connection with Henry’s gold coinage was close and longstanding. Indeed, I could claim to have discovered more about it than anyone else which was why Gregory Edmund had got in touch with me! Most recently, the coinage and its wider background had been discussed in the first volume of my biography of Henry III (published in the Yale English Monarchs Series in 2020) and before that as detailed studies in learned journals.

A second reason was that Henry III’s gold coins are very rare. The only coinage in Henry’s reign before 1257 was the silver penny of which huge numbers were in circulation. In minting a gold coinage, the first since before 1066, Henry was making a new start. It was, however, a failure and only small numbers, in numismatic terms, were minted. Before the Devon discovery only seven surviving examples were known; of these, three were held by the British Museum and one by the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge, the other three being in private hands. The last of the latter to be auctioned (in January 2021) had gone for £437,340. There was likely, therefore, to be very great interest when the new coin was auctioned by Spink. In the event, it was sold for £540,000 (excluding BP), the highest sum reached by any British coin at auction. In all this, there was, however, an obvious question. I had a good idea of why Henry had minted a gold coinage, where the gold had come from, and why the coinage failed. But how had a solitary coin from the mintage ended up in a Devon field near Hemyock?! Could I, asked Gregory Edmund, throw any light on the reason? I had no idea if I could but I said I would try.

First though, how did I know about the coinage at all? Sometimes an historian goes to sources seeking answers to precise questions (I will give an example of that later on). But equally one can make discoveries while looking for something else, or indeed without looking for anything very precise at all – Henry’s gold coinage comes into the latter category. While researching my biography of Henry III, I read through nearly all the records produced by his government, many of them unprinted and housed then in the old Public Record Office in Chancery Lane (now the Library of King’s College.) Of particular interest were documents called ‘the fine rolls’, which recorded offers of money to the king for concessions and favours. Going through these I became aware that in the 1250s, instead of demanding payment in silver, Henry was now demanding payment in gold. So if a lord wished to set up a new market, or if he wanted exemption from knighthood or jury service, he would offer the king gold of a certain weight, a third of a pound being a common amount.

What then was Henry doing? The answer to this question came, again unexpectedly, from another record, namely the accounts of the king’s wardrobe. The wardrobe was an office travelling with the king and responsible for receiving and spending the money for his daily expenses. It was also sometimes responsible for storing treasure. What the accounts revealed was that Henry’s gold was being paid into the wardrobe and once there it was just being kept. In other words, Henry was trying to accumulate a gold treasure. Indeed, he accumulated two such treasures. The first between 1250 and 1253 was almost certainly designed for Henry’s crusade, gold being the currency in the east. (In fact Henry never went on crusade and the gold was used to finance an expedition to Gascony instead.) Once back from Gascony at the end of 1254, Henry started to save gold all over again. It was this second gold treasure that in 1257 that he minted into his gold coins.

Why? The second gold treasure had been saved to finance not a crusade, but a campaign to place Henry’s second son on the throne of Sicily, gold being the Sicilian currency. But once again, Henry’s plans were thwarted. By the summer of 1257, he was running dangerously short of money, just when he was having to raise an army to fight in Wales. He had no alternative but to spend his gold treasure, his only financial reserve. This brings us to a key feature of the treasure also revealed by the wardrobe accounts. Remember, there was no English gold coin, so what was the form of the gold being saved by the king? Again the wardrobe accounts provided an answer. They showed that the gold was either ‘in foil’, so in thin strips of beaten gold, or in foreign gold coins, chiefly Byzantine bezants and Islamic coins known as pennies and half pennies of Murcia. Had Henry gone to the Holy Land or to Sicily, he would have probably changed his treasure into local gold currencies. But there was no local currency in England. If Henry was to spend his treasure, he needed to mint one by turning the treasure into coin. So that is what he did.

The financial emergency was not, however, the only reason for the coinage. Henry had more ambition than that. He hoped that his subjects would wish to change their stores of gold into his coin. By charging for doing so he might make money. The design of the coin itself also had a message. Whereas since 1066 all coins had simply shown the head of the king, Henry’s gold penny showed him sitting elegantly on his throne and holding orb and sceptre. His subjects would surely be impressed by the majesty of his kingship thus displayed. The coinage also paid tribute to Henry’s patron saint Edward the Confessor, for the model was a coin of the Confessor which had likewise shown the king enthroned. The Confessor, surely, would look favourably on the coinage and redouble his efforts to help Henry in this life, as well as (when the time came) speed him to the next.

Henry’s high hopes for the currency were soon dashed. It proved unpopular and minting probably continued for no more than the few months it took to coin the king’s treasure. Record evidence suggests that some 72,000 coins were minted. That may seem a lot but it is tiny compared with the 138 million coins produced when Henry launched a new form of silver penny in 1247. So what went wrong?

Henry had laid down that his gold coin was to have the value of twenty silver pennies. Since it was the weight of two of those pennies, this indicated an exchange rate between gold and silver of ten to one. It has been suggested that Henry, here, was making the mistake of over-valuing his coin but this is not exactly right. The evidence that the exchange rate between gold and silver before 1257 was ten to one is overwhelming. What is true, however, is that the sudden arrival in circulation of large amounts of gold, as the king used his coin to pay his bills, brought the exchange rate down from ten to nine or eight to one. Not surprisingly, therefore, the coinage was extremely unpopular with goldsmiths who found their stocks of gold losing value.

There were other problems. One lay in the high value of the coin, enough to buy food and drink for over twenty days. It was thus pretty useless for the great mass of the population accustomed to silver pennies worth twenty times less. More fundamentally, the ground had not been laid for Henry’s coin by any extensive circulation of gold coins from abroad. The fact that much of his treasure was ‘in foil’, presumably bought from goldsmiths, made the point. The situation was totally different in the next century when Edward III launched his successful gold currency as by then what has been called ‘The European gold famine’ was over and England was awash with foreign coins. It then made every sense for the king to step in with a currency of his own.

What, then, happened to Henry’s gold coins? The great bulk of them were probably spent in Wales during the campaign of 1257, being used to pay the wages of soldiers and buy supplies. A portion also went to Italy to pay debts owed to the Pope. (Two of the surviving coins have an Italian provenance). What was left was sold in Paris during Henry’s visit in 1259-60. But how then did a solitary coin end up in a field near Hemyock in Devon?

Here then was a different form of inquiry, one where the historian goes to the sources seeking to answer a precise question. But, in this case, the question could not be attacked head on. It needed to be approached obliquely and the approach I thought most fruitful would be to find out who were the lords of the manor of Hemyock in the reign of Henry III. Fortunately this was a question to which the legal and governmental records of the period were likely to yield an answer. Indeed, the very first record I looked at did just that. It was a roll containing the pleas heard by the king’s judges when they visited Devon in 1238, a roll edited for the Devon and Cornwall Record Society by my old friend, Henry Summerson. Here a jury stated specifically that the lord of the manor of Hemyock was a man called Richard de Hidon. Some further information about his holdings appeared in a volume called The Book of Fees, a volume containing many thirteenth-century surveys of landholding. Here Richard is found not merely as lord of Hemyock but also of ‘Hidon’, clearly the place from which he derived his name. And ‘Hidon’, as the index of The Book of Fees, helpfully revealed is now none other than Clayhidon, a village less than three miles from Hemyock.

By the time the King’s judges visited Devon again in 1249, Richard de Hidon was dead, for the lord of Hemyock is now stated to be one John de Hidon. John was quite likely, therefore, to have also been the lord of the manor in 1257, the year of Henry’s gold coinage. But was there any evidence linking John to the coinage? Here the obvious places to look were the chancery rolls of the king, all published for this period and indexed, these being the rolls recording the charters and letters the king was issuing. And sure enough, John de Hidon does indeed appear. In November 1256 he secured a letter exempting him from sitting on juries and holding local office, just the kind of concession men of knightly status often secured in this period. It was also precisely the type of concession for which Henry III was demanding payment in gold. Had it been in gold, then, that John de Hidon had paid?

The quest now shifted to the fine rolls of Henry III where, as we have said, such an offer of money would be recorded. (The rolls are all, thanks to the Henry III fine rolls project, now available in translation online: www.finerollshenry3.org.uk). And sure enough, such an offer was there. Finding it was for me the most exciting moment in the whole inquiry. The rolls show that on around 3rd November 1256 John de Hidon offered the king a third of a pound’s weight of gold for his various exemptions. A later note stated he had indeed paid the gold over. The form of the gold was not revealed but since Henry’s own coins had yet to be minted, it must have been either gold in foil or in foreign gold coins.

This evidence then linked John de Hidon, if not to Henry’s coinage, then at least to the gold treasure from which it was minted. Can we get any closer? One possibility is that John’s offer and the coinage are not in fact linked. John’s overlord at Hemyock was the earl of Devon who served in Wales for the king in 1257. Might it be that John was with him and received some gold coins as pay? Perhaps. But my instinct is that there is a connection between the offer and the Hemyock coin.

In 1256 John had paid the king either in foil or in foreign gold coins. He may well have acquired these from goldsmiths at some expense. What is more likely than having heard about the new coins, he decided to acquire a supply against the time he might want to buy more concessions from the king, here incidentally showing an unusual faith in the coinage’s longevity! To acquire the coins he could have exchanged silver or, perhaps, the surplus gold he had left over from his offer in 1256.

If then John de Hidon, lord of Hemyock and Clayhidon, had some of Henry’s gold coins, did he simply drop one himself when out inspecting his Hemyock fields? Or was it dropped by a steward or reeve who had received it in pay? Whatever the truth here, its pristine condition suggests the coin was dropped very soon after mintage in 1257 or 1258. It then lay in its field until discovered by a metal detector over 760 years later.

The gold coinage of Henry III tells us much about the king. It speaks to his imagination and ambition for this was the first gold coinage since before the Norman Conquest. It speaks to the ‘simplicity’ about which contemporaries so often complained, for as the failure of the coinage showed, the project (save as a short term measure to help pay his bills) was largely misconceived. Yet the project speaks as well, in the design of the coin, to the majesty of Henry’s kingship and his devotion to Edward the Confessor, qualities which earned him respect and helped him survive many crises, to die in his bed after a reign of 56 years – the longest of any monarch before King George III.