Gregory Edmund

“OURE TRUSTY AND WELBELOVED ROBERT AMADAS” FIT FOR A KING

THE REMARKABLE LIFE OF HENRY VIII’S GOLDSMITH AND MONEY-MAN

The tradition of gifting an apostle spoon at the baptism of a godchild became especially popular in the latter decades of the 15th Century. Depending on one’s status, a single spoon, a quartet, or even a dozen could be presented for the rite. A thirteenth ‘master’ spoon was on rarer occasions also commissioned to represent Jesus Christ or the Virgin Mary. The earliest surviving examples of such christening spoons date to the first decade of the reign of King Henry VII; mere years after the introduc- tion of date letter hallmarks by the London assay office. A will of this period at York confirms this practice to us, in an audit of: “xiji cocliaris ar- genti com Apostolis super eorum fines” (13 silver gilt spoons with apostles on the top of their ends). Unsurprisingly, this would give rise to colloqui- alisms advanced over the next century by Shake- speare, and is the most likely origin for the mod- ern exhortation ‘born with a silver spoon in one’s mouth’. Aptly therefore the utensil also carries a contemporary sobriquet – a ‘gossip’ spoon.

Apostle spoons could also be presented upon marriage, and in time as the York probate attests, through inheritance. Despite their overt religious connotations, production and use – especially as a full set – reflected their principle function for dining. LeZotte has identified a tangible inter- relationship between this iconography and the principal five human senses, and in particular how their juxtaposition would blend in the Tudor mindset. The opposing views of the Benedictine sacrament and St Augustine posed a serious question: were our senses evidence of the weakness of the human spirit towards omnipresent sin? Or was our receptiveness to such sensations the key to faithful worship (Note 1)? The artistic development of this ‘spiritual battle’ through Tudor tableware – the modern instrument – is as interesting as it is perplexing. One could draw upon wider historic precedents and consider their equivalence to the pseudo-apotropaic devices borne on Greek and Roman vessels utilised in pre-Christian dining spaces. The upheaval of the English Civil War and forcible transition of power to the Puritanical Commonwealth resulted in the successful destruction of almost all pre-1649 plate including the loss of the original English Crown Jewels, rendering surviving specimens frustratingly pauce and in the instance of the Swaythling Spoons, of the highest rarity.

The outward display of personal wealth experienced its own renaissance during this period. The cessation of the ruinous internecine conflicts of the ‘Wars of the Roses’ ceded the geopolitical stage to the active promotion of new favour at the nascent Tudor court. One such beneficiary of this lucrative market was the Amadas family, originally of Tavistock, Devon. William Amadas would be fortunate to sire four sons onto whom he could pass the traditions of his goldsmith’s craft. He had honed his own talents through an apprenticeship to Sir Hugh Bryce, lifetime Governor of the King’s Mint at the Tower after March 1466 and Usher of the Exchange from February 1472 (Note 2). His eldest son, Robert Amadas, would marry Bryce’s granddaughter. In 1492, Robert would become a lowys, and soon after would be officially sworn into the annals of the Goldsmith’s Company in 1494. He would be admitted to their livery in 1503, and go on to serve as a company warden from 1511. By then, his meteoric career rise would, like his grandfather-in-law, already encompass Royal patronage.

On 17th December 1505, King Henry VII had Amadas employed in the office of ‘keeper of the exchange’ at 200 marks per annum to supply bullion to Robert Fenrother and William Rede, the new masters and keepers of the money in the Tower of London, England and Calais. The peaceful accession of King Henry VIII on 21st April 1509 led to the pardon of many subjects proscribed under his father. Robert is one such party listed therein, recorded simply as ‘of London, Goldsmith, late keeper of the exchange of Henry VII’.

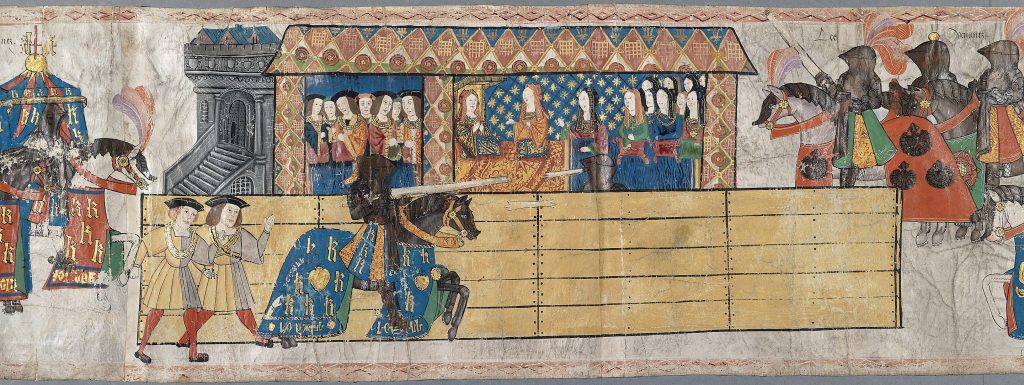

His crime is not clear, but his return to Mint duties as deputy to Lord Mountjoy was swift. At New Year’s Day, 1510, Amadas would be one of seven goldsmiths to share in the payments of 484l. 10s. 8½d. for Royal gifts. However Amadas’ skill was already being viewed above that of his peers. The following month Amadas alone would receive 451l. 12s. 2d. for ‘141oz. of plate of gold stuff for disguisings including 45 roses of gold enamelled and 56 gold Pu[m]gar[nets]’ [sic] as part of provisions for the King’s fortnight at Westminster. Special commissions would continue throughout the year including the gold bullion work on 100 guardsman’s jackets in June at a 1l. per uniform, and a further 266l. 18s. 4d. in September for ‘letters, wreaths, harts and roses of fine gold’ for the King’s trip to Shaftesbury and Salisbury. In October 1510, a loan of 1,000l. received directly from the King at Greenwich in March would be repaid. The following year, Amadas would receive payments of 163l. 6s. 8d and 1,146l. 11s. 9d for the provision of “259 letters of H., weighing 89 oz. and 218 letters of K., 81 oz. 2 dwt.” for the jousting pageant held at Westminster on 12-13th February 1511, and associated dinner termed “the Golldyn Arber in the Archeyerd of Pleyser” held at Whitehall. The spectacle, initiated by Henry’s ‘Tournament Challenge’ was organised to celebrate the birth of his heir presumptive Henry, Duke of Cornwall, on New Year’s Day. It told the story of four knights, Ceure Loyall, Vailliaunt Desyre, Bone Voloyr and Joyous Panser, to be played by the King, Sir Thomas Knyvett, Sir William Courtenay and Sir Edward Neville respectively. That night the King wore 887 pieces of gold, his Master of Horse, Knyvett, 893 pieces. Official accounts state that together they would lose a scarcely comprehensible 225oz. of gold from their dress; but that Amadas would receive back 214½ oz soon after. Were further evidence still needed for the burgeoning success of Amadas’ craft, that year the King would provide only partial funding for the ‘1,000l. needed for repairs at Windsor Castle’.

In November, a further 200l. would be granted Amadas for ‘finishing 100 jackets of the Guard’. Unsurprisingly the following New Year, goldsmiths’ rewards for the King’s gifts (775l. 0s. 3½d.) came to be listed separately from Amadas’ own personal contribution of ‘6 bolles with a cover gilt’ (59l.). The New Year would also demonstrate the importance of Amadas’ dual role in embellishing the King’s lifestyle at court, but equally in the guarding of his Royal specie. Between February and July, Amadas and his colleague Edward Jourdan would receive at least 6,987l. 19s. 9d. ‘in refuse groats, half- groats, romaignes and refuse pence’. It is evident from these accounts that Amadas was integral to the maintenance of the coinage against the blight of ‘clipping’; the unscrupulous practice of which had alarmingly defrauded the state 2,476l. 4s. 9d. from these parcels alone. The recall of lightweight coinage would continue in January 1513, but Amadas’ services were no sooner sought for ‘furnishing 200 jackets for the Guard’ at 400l. with a further 50l. paid for the embroidery. This commission came in the immediate aftermath of another magnificent pageant called “the Ryche Mount” for the feast of Epiphany on 6th January 1513, in which Amadas supplied 375½ oz. 2¾ dwt in gold bullion for “a mountain of gold and precious stones, set with herbs of divers kinds, and planted with broom to signify Plantaganet, and also with red and white roses…, apparelled in crimson velvet and goldsmith’s work, of korryas kast and ingyen” [sic]. In May, further accoutrements were required from Amadas, including ‘gilt and white spangles for 100 jackets of the best sort’; ‘the finishing of 13 long coats for the henchmen’; and ‘making for the King whisseles, chaynes, braunches, bottons, and aglets’ [sic] for which he would receive 1,937l. 4s. 5d. In September he would ‘garnish a head piece with crown gold, a salet [sic] and the mending of a shapewe’ at a cost of 462l. 4s. 2d.

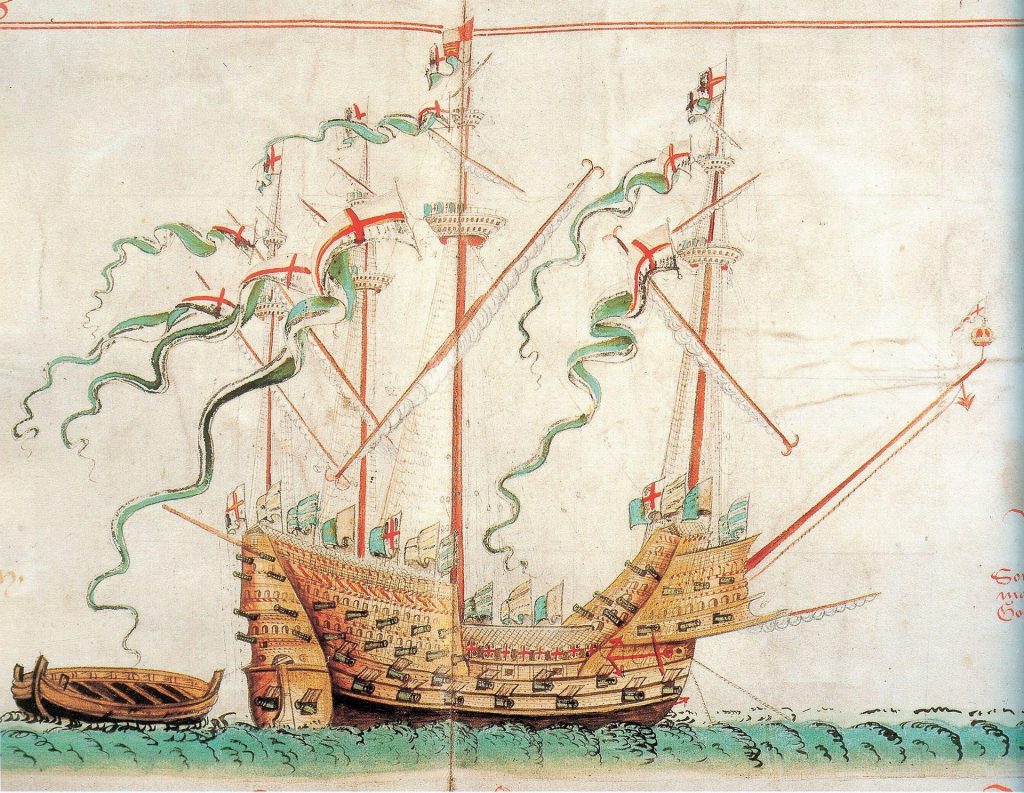

In February 1514, Amadas would be again commissioned at 100l. for the furnishing of 600 jackets ‘of the second sort’ for the King’s Guard at the installation of the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk. A similar Royal expense was required in May for ‘600 plagards of green satin of Bruges for the Guard’ costing 1,083l. 11s. 5d. However, March would see the completion of Amadas’ most important Royal commission yet: ‘a great seal of silver and jewels’ at the enormous cost of 1,576l. 4s. 8d. Evidently this would be the Great Seal of England later used by King Henry VIII in the signing and sealing of the Anglo- French non-aggression pact of 7th August 1514. However Amadas could not rest, for his next assignment would be the rigours of an assay of his coinage at the Trial of the Pyx on 27th March 1514 (Note 3). This too would be followed by a further order for harnesses and trappings for the Royal procession ‘at the hallowing of the King’s great ship called The Henry Grace a Dewe’ at Erith on 13th June. For these services, he would receive another 230l. 12. 8d. In September, a further 1,906l. 8s. 4d. was forthcoming from the Crown for ‘gold work’ related to the King’s offerings on the ‘rode of Grace at the cross of St Austin’s and St Austin’s shrine’

Were 1514 not exhaustive enough, Amadas would initiate seven court cases against his gentleman debtors including the brother-in- law of Edmund Dudley, author of ‘The Tree of Commonwealth’, who had been executed for ‘constructive treason’ and unjust financial practices in August 1510. Awaiting judgment, Amadas would receive a further 134l. for the production of ‘gilt spangles delivered to Wm. Mortymer, broderer’ [sic] for the trousseau worn by the King’s younger sister Mary Tudor at her marriage to King Louis XII of France. This particular commission would last throughout the following winter, as Amadas was retained by Sir Henry Wyatt, Clerk of the King’s Jewels, to repair the plate and diamond jewellery destined for Queen Mary’s use at the French court. The production order for Amadas at 102l. 14s. 4d., over half the total expenditure, was pre- authorised by the King via his Treasurer of the Chamber, John Heron ‘content upon his sight thereof, Henry R.’ Following settlement of his latest bill at Richmond in April 1515, Amadas’ Royal commissions apparently dried up. It is known that he regained the wardenship of the Company of Goldsmiths soon after, and this enabled him to seek further private commissions in the interval. The will of Amy Brent proven on 3rd May 1516 poses just this eventuality. Her bequest to daughter Margaret, wife of George Nevill, 5th Baron Abergavenny included “XIII sylver spones of J’hu and the XII Apostells” [sic]. After Amadas’ own death in 1532, his widow Elizabeth would remarry Sir Thomas Neville, younger brother of the 5th Baron. These close familial ties provide a tantalising origin for Brent’s spoons; and with it a probable reference to one of several sets of Apostle spoons that Amadas would be commissioned to make over his illustrious career.

Other Royal commissions returned upon the occasion of the christening of Princess Mary in February 1516 and the Order of the Garter on 24th April 1516. At Court in Eltham, Amadas submitted a bill for 481l. 5s. 1¼d. ‘for 4 saddles for 14 horse harnesses, wrought with spangles and tassels of silver’. For the visit of the King of Denmark in June, Amadas would provide ‘silver bells, buckles, bosses and silver and gilt nails for the King’s use’ at a cost of 31l. 8s. 3d. In December, the King would further recompense Amadas and his mint colleague Ralph Rowlett for “waste of gold, partyng of silver and its alloy, as well as the coinage of gold – 43l. 8s. 9d.” Amadas’ role would then expand at Court, as he was employed to facilitate the further personal requirements of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Following the resignation of Archbishop Warham in 1515, Wolsey had been appointed Lord High Chancellor, a position which granted him custody of the Great Seal of the Realm. Evidently aware of Amadas’ work, Wolsey began a running account with the goldsmith from Michaelmas 1518, almost immediately entrusting him the commission for his New Year gift to the King for January 1519 and every year thereafter. King’s commissions again returned with an order for “spangles for the Guard’s jackets” (1,419l. 18s. 2d.). In June 1519, Henry FitzRoy was born, the only acknowledged illegitimate child of the King. Wolsey would be appointed his Godfather, but Amadas’ inventory records no customary christening gift at this time. Instead that Autumn, Amadas would furnish ambassadors in Flanders and 4the Cardinal in Rome gifts of plate totalling 494l. 13s. 9d. In March 1520, he would receive a further award of 104l. 9s. 0d. for gifts of plate to the French ambassadors on their visit to Scotland. Wolsey meanwhile required of his jeweller a thirteen- link fine-gold chain that he would wear ‘en escharpe’ at his meeting of the French king at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in June 1520.

In November 1520, Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham gave instructions to his servant Robert Gilbert ‘to pay Rob. Amadas for certain pots made for christening lord Abergavenny’s child’. Following the death of Margaret eighteen months prior, the 5th Baron Abergavenny had re-married Lady Mary Stafford, the youngest daughter of the 3rd Duke. Stafford had previously borrowed from Amadas (Note 5) and would again use his services when exchanging his own 17oz gold chain ‘to be molten and coined into 24l.’

In March 1521, the King paid Amadas a further 1,184l. ‘for plate’, all the while Court suspicions about Buckingham’s own manoeuvring grew. On 9th April, Buckingham was summonsed to answer to the charge of treason, having allegedly ‘imagined and compassed the death of the King in seeking the prophecy of a monk about the chances of the King producing a male heir’. Six weeks later he would be beheaded on Tower Hill, condemned amongst other crimes of being too close to the throne as a blood nephew of King Edward IV. At his trial, circumstantial evidence of the Duke’s motives were presented through the actions of his servant Gilbert in buying ‘cloth of gold and silver and silks, each time to the value of 300 marks, intending to give them to the knights and gentlemen of the King’s guard to procure adherents.’ Cambridge More damning evidence came against the Duke, when his son-in-law confessed to a conversation held on the 10th September 1520 at his gallery at Blechynglegh – “if the King should die, he meant to have the rule in England”. For concealing this discussion, Baron Abergavenny would fined, imprisoned in the Tower of London, stripped of office and household, its contents escheat.

Amadas’ proximity to Buckingham and Abergavenny could easily have led to his exposure as a treacherous colluder. However, his past loyal provisions to the King and Cardinal Wolsey allowed him to fade quietly back towards his official mint duties. His special commissions for the Crown between 1506 and 1521 had by now run to some 36,000l., including the refurbishment of uniforms to the King’s Guard totalling 6,750l. or the equivalent of 3,000 oz. of wrought gold (Note 6). Following the forfeit of Buckingham’s plate, of which several thousand ounces of silver and 81 ounces of gold were added to the Royal Jewel House, it is probable that Amadas received the remainder for re- coining. An inventory of the Jewels undertaken by Sir Henry Wyatt in February 1521 listed 34 gold spoons, most the New Year Gifts bought for the King from courtiers; alongside 185 gilt or ‘white’ apostle, slip-topped, griffin and wrythen- knopped spoons. The audit marked some as from the Buckingham escheat, while others were undoubtedly Royal gifts via Amadas, such as the eight parcel-gilt spoons weighing 9¾ ounces gifted by Groom of the Wardrobe of Robes, James Worsley in January 1513 (Note 7). On 23rd July 1521, Thomas, Lord Darcy wrote to the King’s new solicitor-general Richard Lyster enquiring after “a sure and good carrier of my plate” including within a further instruction: “to send me 24 plates and trenchers of silver parcel gilt, in the best French form, from Amadas.” In October, Lyster responds confirming that “he will be sure to send the plate, with such accounts as will content him”, but he believed that “all the receipts will not pay both assignment and the King and redeem your plate” so Darcy’s receipt “must now be paid to Amadas.” In November, shortly after Allhallowtide, ‘no money had come’ so Darcy opted to pledge the 40 marks of plate to Amadas in lieu of settlement. Delayed payments would become a recurring feature of the period, for in June 1522, Clerk of the Counting House, Edmund Peckham complained to Cardinal Wolsey that “he had not received 9,000l. of the City of London, and most of that he had received was in pennys” [sic]. He stated that Robert Amadas was in possession of “chains and plate to be coined to the value of 700l. which Peckham will have by Saturday night [28th June].” By April 1523, Amadas would purchase only 25l. 12s. 7d. of the gold jewellery from the estate of Lord Monteagle, perhaps reflective of the continued restrictions on his own ready capital.

By September 1523, Amadas would further resort to accepting old plate in part-payment for Cardinal Wolsey’s most recent commissions. Included within this parcel were: ‘iij gilte Sponnes poiss iiij oz. iij. qrt. d.; oone Sponne with a flat Steyle poiss j oz iij. qrt. d.; vij Sponnes gilte of divers makyngs poiss ix oz. d. d. qrt.; twoo doson of Spoones with flat Steylis poiss. xxvj oz.; and, item resceavyd more xij. Sponnes poiss xj oz.’

Wolsey’s evident money troubles were alluded to again by Archbishop Warham in the prelude to the signing of the Treaty at the More: ‘as to the 500 marks he has not paid of the 1000l. Wolsey knows of, has delayed the payment that he might call the more instantly upon some of his old debtors. If he does not recover his debts now, fears that he never will. They may think he has great need, as he paid Amadas a good part of the 1,000 marks paid already in plate.’ Cash flow is probably also the reason for the Sheriff of London’s surprising warrant for Amadas’ apprehension in November 1523 at the behest of one William Honnyng. However debtor’s litigation would not prevent Amadas’ prestigious elevation to the King’s Jewel House and appointment as Principal Warden of the Company of Goldsmiths by September 1524. A further sign of the Royal confidence came at Christmas, when the King offered his surplus wine to trusted courtiers at 6l. and 8l. per tun. Amadas was one of a handful of beneficiaries of this ‘generosity’, affording us even safe knowledge of the fine Gascon and Rochelle wine he would be sampling as he rendered the first parcel of the ‘Swaythling’ spoons.

His first duty as Acting Keeper of the Jewel House would be receipt of the King’s plate at Eltham on 18th January 1526, including: “A gold bawderick, with nine fair balasses standing between angels, and 36 pearls, 98¾ oz. A collar of Spanish work, with 16 fair balasses and the following diamonds: 16 great pointed diamonds; 2 great rocked; 2 great table, square lozenged; one long table, square; one heart-fashioned; one table, six-squared; a great triangle; a long lozenge; and the Great Mirror, 88 oz. Another collar, with 12 fair balasses, and 5 table, 2 pointed, 4 rocks, and 1 triangle diamond with 36 pearls, 55½ oz. A collar of garters with St. George on horseback, one triangle diamond on the horse’s buttock, and a shaffron of diamonds, 48 oz. 1½ q. A blue and green enamelled girdle, with 12 balasses, 63½ oz. A gold chain, gable fashion, 124½ oz.” Following an evidently satisfactory probationary period, on 20th April 1526, Robert Amadas was officially appointed ‘Master of the Jewels’ by the King at Westminster. Shortly thereafter the King and Wolsey’s attention returned to the state of the English coinage. Following a series of Summer edicts, on 30 October 1526, the King issued a recoinage proclamation including the retariffing of his pound Sovereign to be current for 22s 6d, and an authorisation for new coins including ‘the George Noble’, and a ‘Crown of the Double Rose’ to replace the short-lived ‘Crown of the Sun’ previously authorised. The new coins would reflect the King’s latest title as ‘Defender of the Faith’ as granted him by Pope Leo X on 11th October 1521 (Note 8). On 3rd December, Amadas advised Archbishop Warham and his bearer, Ewyn Tomson to petition the King for his personal pleasure for the furtherance of Canterbury Mint activities, but Warham would only proceed in the knowledge that Wolsey would do the same for York and Durham. The recoinage would further ease the facilitation of the National ‘Subsidy’ devised by Wolsey and Heron in 1523, permitting the implementation of a 5% income tax to finance the King’s expansive foreign policy.

However, in January 1528, serious allegations about irregularities with the new coinage surfaced, for which Amadas and others would be forced to account.

Complaints included“handling of the beam at their own pleasures; without comptrolment or oversight of any indifferent sworn person; that they occupy men’s money in their own shops at their pleasures, and to their singular lucres; that they make men wait for their money; for some men say that they have tarried two or three months; and that they keep not the sheer indyfferently neither of gold nor of silver,” heavier, &c, as well as not giving true value for foreign gold, and refuse controlment.” In response, Amadas appealed as ‘an aunysant honest man and deputy to Sir HenryWyatt which hath continued over and above this 30 years’ and complained that the allegations were based on the flawed logic that one could melt a 1lb of silver for as little as 2½ d. as proven by his accusers failure on two attempts (Note 9).

The embarrassing failure in the Autumn of 1526 of the ‘Crown of the Sun’ coinage, which had been issued to compete with the French Ecu d’Or au Soleil was also to be blamed on Amadas. Further charges were laid that the coins had been issued too intrinsically valuable, with their recall prompting unacceptable undervaluation of their replacements the “Crowns of the Double Rose” (Note 10). His firm riposte ensured his survival in post under Mountjoy, the wealthiest English nobleman at Tudor court would endure until his death.

Between 1527 and 1529, Amadas was separately commissioned by Cardinal Wolsey with the repair and supply of gilt plate to the Abbey of St Albans, Saint Frideswide’s College (now Christ Church), Oxford and the Cardinal’s College, Ipswich. No sooner had the plate been received by their respective institutions, had wider geopolitical events enveloped Wolsey. His failure to further the King’s divorce to Katharine of Aragon; the collapse of his Amicable Grant after uprisings in East Anglia, and a botching of foreign policy surrounding the Battle of Landriano all propelled his spectacular fall from grace in July 1529. Forfeiting Hampton Court, Wolsey was permitted to retain the Archbishopric of York and his residence at Cawood Castle. The King’s men would subsequently visit Wolsey’s new patronages and seize much of this newly delivered plate, identifying it as Wolsey’s personal property. In November 1530, the Earl of Northumberland arrived to arrest him on charge of high treason. He would die before reaching London. On the previous decade, Amadas had furnished Wolsey with 5,002l. 0s. 9¾d. of plate (Note 11). However the volume of orders passed to Amadas from March 1529 – March 1532 would be equally vast, charting not only this downfall, but also the requirement to outsource much of his own work to fellow goldsmith Cornelius Hayes, including: ‘For the King, the great silver gilt cross which was for my lord Cardinal 973¼oz.’ (Note 12). Much like the Cross, all the Cardinal’s effects became forfeit. An inventory of his surviving effects at Cawood included: ‘gilt plate – 13 spoons with Christ and the Apostles’ but frustratingly no record of scratch weights.

Besides the Wolsey inventory, the death of Lord Monteagle in April 1523 provides an important further account of the personal plate held amongst the nobility contemporaneous with the commission of the first ‘half ’ of the Swaythling Set.

It gives direct evidence of the fashion for six Apostle spoons in a dining service, as well as evidence of a practice of mixing various ‘sets’. Four other styles would appear in Monteagle’s inventory to complete an assemblage of a dozen spoons including, “three with strawberry knoppes, one a writhen knoppe, one a daisy-knoppe, and one with a dragon upon the stert”. The gulf in grandeur between the Swaythling and Monteagle sets is also evident, with the latter Apostles cumulatively weighing only “8½ oz” (Note 13) in comparison to the Swaythling spoons weighing a remarkable 124/5oz. Interestingly, as Monteagle had died owing the King 111l., Sir John Hussey, the Royal Chamberlain was sent portions of the relict plate in settlement. His receipt of 21st October 1524 confirms: “… Parcel Gilt: Candlesticks for altars, basins, cruets, a pegen with a cover, 4 candlesticks like troughs with 4 broches and 8 noses, spoons with wrethen knops, apostle spoons etc, 758½ oz. at 3s. 6d.= 157l. 4s. 9d …” (Note 14). Evidently Henry’s passion for functional silverware was never satiated as he opted to add Monteagle’s own spoons swelling his personal collection to nearly 200 pieces.

“The outward display of personal wealth experienced its own renaissance during this period. The cessation of the ruinous internecine conflicts of the ‘Wars of the Roses’ ceded the geopolitical stage to the active promotion of new favour at the nascent Tudor court”

Despite his personal association with condemned traitors; the embarrassment over the King’s coinage; and an increasing outsourcing of commission responsibilities, the final months of Amadas’ life make clear that he had personally lost little if any command of the Royal favour. Still responsible for at least 10% of the two hundred gifts made to King Henry and New Year’s Day 1532, the King had in turn presented Robert with his own 36.75oz covered cup. Amadas had reciprocated by presenting the King ‘six Sovereigns in a white paper’ (Note 15). As the design for the Fine Sovereign did not radically change between 1526 and 1544, the meaning of this gift is somewhat unclear. Many gifts of gold Sovereigns are made to the King from Dukes and Abbots on this occasion, all described as being ‘within a glove’. It would seem strange therefore that a man of Amadas’ talent would risk the underwhelming appearance of paper. Perhaps it reflects a change of pyx mark on the coinage for which the King is given ‘the first strikings’, or more tantalisingly an allusion to the special piedfort strikings of the issue of which a ‘Double Sovereign’ (Note 16) and a ‘Treble Sovereign’ (Note 17) exist in the British Museum collection from the last years of the reign of Henry VII when Amadas also worked at the Mint. This annual ritual would however be overshadowed by the King’s refusal of the gold cup from Catherine of Aragon and the lack of any gift for her, or his daughter Princess Mary in return, yet the happy receipt a richly decorated set of Pyrenean boar spears from his new court interest Lady Anne Boleyn.

The Swaythling Spoons are available for sale by private treaty until the end of September 2022.

For further information please contact Tim Robson, [email protected], or Gregory Edmund, [email protected].

Notes

- Annette LeZotte (2009), The Primacy of Taste: Apostle Spoons and Domestic Ritual in Tudor England

- REC Waters (1876), Genealogical Memoirs of the Extinct Family of Chester of Chicheley, Their Ancestors and Descendants: Volume 1, page 17

- 4th April SP Hen VIII, 7, fol 121

- FitzRoy’s appointment as the Duke of Rich- mond in 1525 would see Wolsey commis- sion Amadas to produce for him ‘a Garter of crown gold’

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 3, 1519-1523 (R. MS. 7. F. XIV. f. 1. B.)

- 6 T Schroder (2020), A Marvel to Behold: Gold and Silver at the Court of Henry VIII, pp 51-53

- 7 P. Hen. VIII, 229, f. 104. R.O.

- Cotton MS Vitellius B IV/1

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 4, 1524-1530, 3867

- Ibid

- Ibid, 6748, page 11

- Ibid, 5341

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII: Volume 3, 1519-1523, no. 2968

- Ibid

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII: Volume 5, 1531-1532, 686

- BM 0713.1

- BM 392