Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis & Alexandra Magub

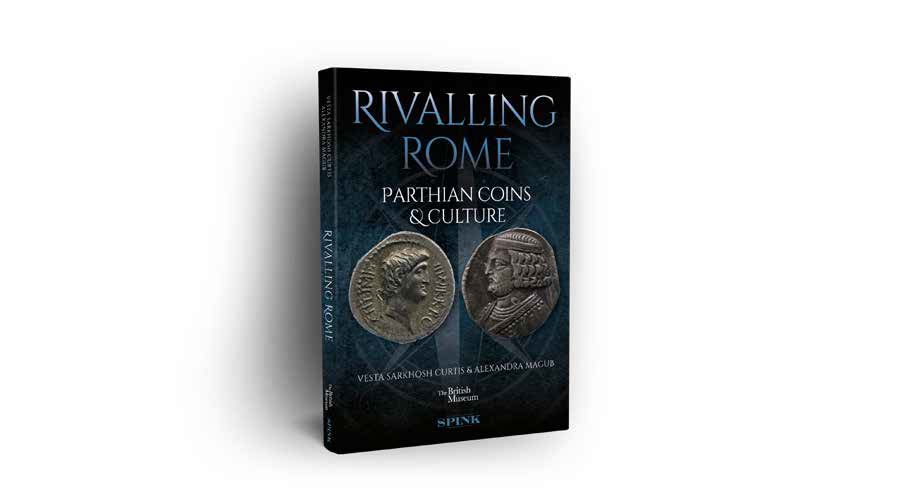

RIVALLING ROME: PARTHIAN COINS AND CULTURE

Equal to Rome in power and military might, the horse-riding Parthians were crucial to trade on the Silk Road.

The term “Parthian” comes from the name of the satrapy of Parthava (Parthia), a province that was once part of the empire of the Hellenistic Seleucids, and before that of the Achaemenid Persians. In around 247 BC, the East Iranian Parni clan under the leadership of a certain Arsaces conquered this region in north eastern Iran/south-western modern Turkmenistan. Andragoras, the Seleucid satrap of Parthava, was killed in the city of Nisa and Arsaces and his followers established control over the highlands of eastern Iran. From here, they continued their advance into northern and western Iran, subjecting territories that had traditionally been inhabited by Parthian and Median peoples. As a result of these conquests and movements, the descendants of Arsaces (the Arsacids) became assimilated with the peoples of western Iran, and consequently abandoned their East Iranian language in favour of the west Iranian Parthian language. By 141 BC, the Parthian state had been extended into Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). From now on the term “Parthia” became associated with the entire state of the Arsacid dynasty, and classical sources referred to the Arsacids as Parthians.

The Arsacid Parthians are one of the three important ancient Iranian dynasties who ruled for almost five hundred years over a vast region stretching from the River Euphrates (in modern Syria and Iraq) to the River Sind (in present day Pakistan and India). From the early 1st century BC, the Parthians became Rome’s most powerful opponents in the East. By now, they had established a substantial empire and subjected various local kings to their rule. Their encounters and engagements with Rome were often related to the annexation of territories that lay between them and provided access to important trade routes. Armenia was particularly affected, especially as its kings were often related to the Arsacid King of Kings, but at times Roman sympathisers were put on the throne. Nevertheless, times of war were complemented by peaceful periods. It is interesting that throughout the centuries of rivalry, we also hear of political exchanges between the two superpowers and visits to their respective courts.

Despite the collapse of the Arsacid Parthian Empire in AD 224 and the subsequent rise of the Persian Sasanians, Parthian influence endured in the art and culture of Sasanian Iran. Characteristic features of Parthian art that continued into later centuries and even into the Islamic period are numerous.

Gold aureus of Lucius Verus. On the reverse the emperor gallops on a horse brandishing a javelin. A prostrating enemy appears under the horse’s hooves.

They include the use of frontality rather than profile in figural representations, and the costume of jackets, tunics and trousers, as well as the long-sleeved overcoat, which were all part of the heritage of the Iranian riding peoples. In architecture, the four-eyvan plan consisting of four facing vaulted structures opening into a large open courtyard is known, for example, in the 1st-2nd centuries AD from the cities of Hatra and Assur in Mesopotamia.

This feature continued into the Sasanian period. The eyvan, together with the elaborate stucco decorations of palaces, were also adopted in Iran for mosque architecture and the decoration of the mihrab (or prayer niche) in the Islamic period. In addition, the Parthian concept of chivalry and heroism has echoed throughout Persian literature and today resonates in the modern Iranian athletic tradition of the zurkhaneh (“House of Strength”).

Despite the importance of the Parthian Empire and its lasting influence in the art and culture of the ancient Near East, very little attention has been paid to the understanding and evaluation of this period. The paucity of primary written sources has made scholars depend heavily on classical sources from the Greco- Roman world, which by nature are biased in their perspective. In addition, the European romanticism of the 19th century elevated the legacy of classical antiquity in order to create a European identity based on the glories of ancient Greece and Rome.

There was little understanding for the opponents of these western civilisations, Greece and Rome, who were all referred to as “barbarians”. In Iran itself, the Parthians were also regarded unfavourably by their successors, the Sasanians, who were keen to associate themselves with the Achaemenid Persians of

southern Iran. For a long time, modern Iranians also regarded the Arsacid Parthians as a derivative dynasty of Hellenistic Greece, particularly in view of the use of Greek inscriptions on their coinage. However, this practice can be compared with the use of Arabic on coins and documents of Iran in the Islamic period, which does not negate the Iranian-Persian character of Islamic Iran; or the use of Latin on medieval and modern European coins.

The coinage of the Arsacid Parthians and their local kingdoms provides an important primary source for the understanding of this period. This, together with evidence from cuneiform tablets, rock reliefs and other sources, offers a more objective view and better understanding of the Parthian Empire, its relationship with Rome, as well as the legacy of Parthian culture in the Iranian world. With coins – and objects including belts, figurines and a Roman cameo – the displays offer a fascinating insight into this influential ancient Iranian culture.

Article is extracted from Rivalling Rome: Parthian Coins and Culture by Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis and Alexandra Magub, published by Spink Books in association with the British Museum in April 2020. It was created to accompany an exhibition of the same name in the Coins and Medals Department at the British Museum, and explores the interaction and confrontation between two superpowers of the ancient world. For more information please visit www. britishmuseum.org. To order a copy of the book please visit www.spinkbooks.com or email us at [email protected]. RRP £20.