When did you first become interested in coins?

When I was three or four years old, I had a collection of half a dozen farthings in a shoebox. I recall being upset when my mother spent them! Fair enough, I had taken them from her roll-top desk in the first place. I’m sure all collectors will know that there were 960 farthings to the pound sterling, and, yes, goods were commonly priced in farthings in the early 1950s, after all 19s/11¾d sounded so much less than £1!

About four years later a Canadian soldier visited us. He had been in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp with my father’s twin. Listening to him was a formative experience. He brought a half-empty, 8cm high tobacco tin, which contained my uncle’s entire worldly estate – tarnished brass uniform buttons and buckles – but also six ancient coins. This was the start of my serious interest in coins.

Eventually, the coins were identified, with the help of fellow members of the Yorkshire Numismatic Society, as C2nd CE Kushan coins from the Taxila mint. My uncle had been stationed at nearby Peshawar, before the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, for which he had volunteered, were shipped to Burma to face the full fury of the Japanese advance. More recently, I have seen photographs of the ancient Peshawar coin exchange, which still operates in the bazaar and is, very likely, where my uncle bought these coins.

This early interest in archaic oriental coins continued. When I was 12, I recall visiting Manchester, where my mother ran her small business. I took myself, by trolley bus, across town to Shudehill Market and spent five week’s pocket money on a Chinese knife coin, supposedly from C11th BCE. Liz Pirie, at City of Leeds Museum, soon put me right – it was a C19th copy of an C18th forgery!

Overcoming the disappointment, I still found these coins fascinating, especially when I later discovered their part in the disastrous economic reforms of the usurper Wang Mang.[1]

Around this time, we used to holiday in Padstow and visit Port Isaac, where I befriended the local antiques dealer, who was especially generous in selling me old coins very inexpensively. It was a captivating introduction to collecting. Back in the early 1970s, archaic oriental coins were ideal for someone on a tight budget. My first salary as an articled clerk, after graduating, was a princely £800 per annum. But in those days, a decent punch-marked Indian silver coin from C5th BCE could be had for as little as £4 in fine condition.

It was only much later, around 1990, that I focused on a much-neglected area of English numismatics, which I prefer to call the Conversion Period, rather than the ‘Dark Ages’ – the sophistication of the iconography belies that epithet.

[1] Tye, R., 1993, Wang Mang (South Uist).

What attracted you to sceats in particular?

The history and the mystery. Little documentary evidence survives from the period. It is particularly difficult to put the largely uninscribed and remarkably diverse Southumbrian series into any economic, social, political, religious or art-historical context. To make any sense of the early silver penny, one has to draw on all the available evidence, such as the iconography.

The Northumbrian coins are literate and, therefore, less problematic. Right back to varieties of the enigmatic York gold shillings, they are all inscribed with the names of issuers who were historically documented, mainly by Bede. I acquired my first styca in 1975 and first bought a sceat in 1989. At that time, there were very few collectors of early pennies, quite probably due to the small module – or flan size – and typically naïve standard of engraving. This meant that not only were many designs difficult to recognise, but also the series was open to counterfeiting – both contemporary and modern.

Professor Wim de Wit was an enthusiastic collector but acquired coins from very few sources and at the top of the market. During the 1990s, I was preoccupied with launching a technology business, and funds were tight, to say the least. Fortunately, these coins were now being found by metal-detection and there were few buyers for such a little understood coinage.

Why sell?

It was my intention to leave the coins in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, long-term. However, since the death of Mark Blackburn (and Michael Metcalf of the Ashmolean) the context of metal-detectorist finds has changed, and consequently museums’ attitudes and focus have shifted. The latter is due to a number of factors: the major collections have been published through the Sylloge series; there is greater availability of digitised images to study online; and the museums have negligible acquisition budgets.

Personally, I intentionally focused on this very narrow niche, as I found this fulfilling especially in advancing our understanding of the coinage. In more recent years, however, my rate of acquisition has dropped, and I feel I have reached a plateau: I have achieved more than I could have expected when I began the collection. Added to this, my perspective has been altered with the pandemic.

The best way to encourage wider interest in the coinage of this period, and bring it into mainstream numismatics, is to disperse rare specimens to the rapidly-growing body of active collectors. This will benefit the wider numismatic community. And for me personally it will be a release to move on. The time has come to exchange old money for new!

Won’t you miss collecting?

The Conversion Period coins themselves have been in the Fitzwilliam Museum for the last

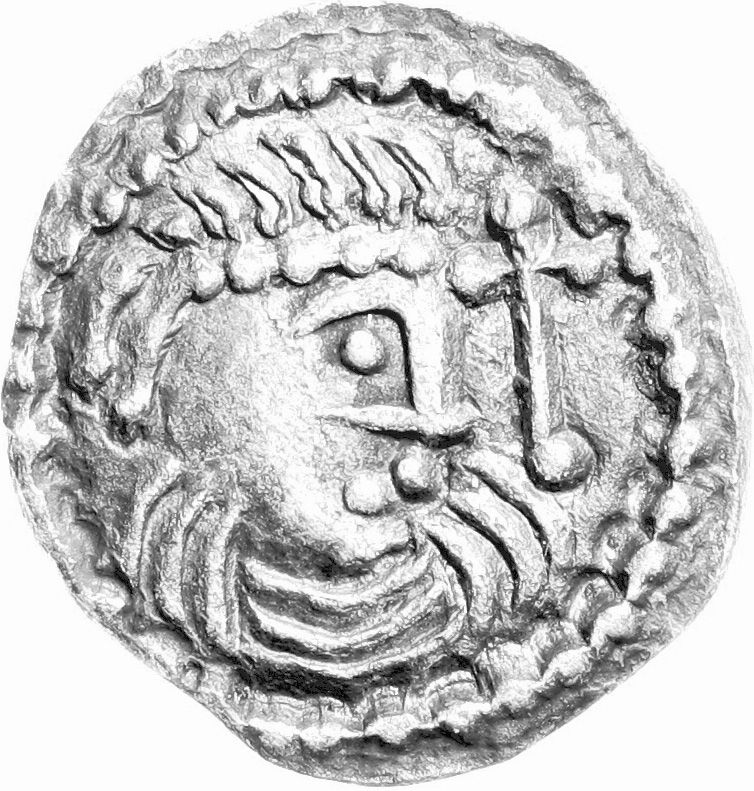

A rarity from Series H, Hamwic.

ten years and I have added very few specimens to the collection in the last couple of years, so I’ve become rather detached from them.

I am often sent images of coins by metal-detectorists and asked to identify them, and I find that very satisfying, so I anticipate I will remain involved in numismatics in this way. Besides, I intend to continue to help organise the biennial symposia in early medieval coinage.

Why do you think sceats have become so popular with collectors over recent years?

I look back to the first Standard Catalogue that I bought, in 1960. Even if I had been able to afford the modest £12 most of these types then cost, sceats were simply unavailable. It was only with the advent of metal-detecting equipment capable of sensing these tiny coins, that sceats started to appear on the market. Even then, the literate Northumbrian pennies aside, the coins were beyond comprehension. Big, bold and

beautiful hammered coins were more tactile and had greater eye-appeal for most collectors.

The heavy lifting to bring meaning to the hugely varied types was done for early pennies by Stuart Rigold, Michael Metcalf, Mark Blackburn and Anna Gannon and for stycas by Stewart Lyon and Elizabeth Pirie. If I did anything, it was to make existing work more accessible. Michael’s Thrymsas and Sceattas in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford is certainly a magnum opus, but it is somewhat opaque to the non-specialist.

My Sceats: An Illustrated Guide was originally my personal aide memoire for visually navigating the diverse imagery. I found it so useful, I thought it would help others if I published it. It was well received, and evolved into Sceatta List, as the need to revise the classification became more acute. I hope the large, heavily-illustrated format has been helpful – especially the more robust, second edition published by Spink and shortly to be superseded by a third edition.

The opportunity to expand the early Anglo-Saxon section in Spink’s Coins of England in 2011 was most welcome and again, hopefully, improved access to this complex series.

With greater availability and understanding, interest has inevitably increased.

Do you have any advice for collectors, many of whom are new to this field?

For collectors developing a serious interest in early pennies, the choices would be to build a representative selection or focus on one group. The former is perhaps more challenging, in that it requires patience – some types do not appear for a considerable time, then, by coincidence, a couple will come onto the market. The latter, more convergent, approach, akin to a die study, gives a lot of scope for contributing to our knowledge of the production and use of early pennies. Both approaches are very satisfying.

Your doctoral thesis has been published. What can sceats tell us about the Dark Age that is

unique to its coinage?

As soon as my initial application to study for a PhD had been accepted at York, I contacted Galata Print, who had published Liz Pirie’s Coins of the Kingdom of Northumbria, despite the overwhelming opposition to her classification.

In private correspondence to her in June 1987, Michael Metcalf had written: “You have invested an enormous amount of skill and devotion and effort into the Yorkshire stycas, and the results …will be to make the styca series one of the show-pieces of medieval numismatics, with enormous potential for future research. That’s why it is a public as well as private tragedy if you perversely throw it all away.”[1]

[1] I was fortunate to be able to salvage Pirie’s archives from Cambridge and Edinburgh. After purging them of copious rewritings of her prolific output, I deposited them, appropriately, at City of Leeds Museum, where she had been curator for many years.

Assembling the illustrated corpus of stycas in such detail was a magnificent achievement by the indefatigable Pirie but was rendered inaccessible by her characteristically feisty refusal to compromise on taxonomy.

I was delighted when, after a little badgering from me, Paul and Bente Withers of Galata excavated their archives and sent me the entire proof gratis. With the benefit of my brother’s IT skills, we were able to digitise the whole corpus as a dataset, so that it could be searched and sorted at will. This provided me with a wealth of detail for assessing the regional distribution of stycas in the north. A similar amount of material was assembled on sceats, largely from the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Early Medieval Corpus. The co-occurrence of coins and artefacts, as recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme, gives an illuminating insight to the economic development of Northumbria.

Briefly, my thesis concluded that as the metallic value of the coinage fell, the volume increased, and smaller transactions were settled in coin. Not an earth-shattering finale in itself, but one based on a wealth of empirical evidence.

Other conclusions discussed the balance of power between church and state; the substantial economic differences between the managed lowland estates and the more enterprising, sheep-rearing Wolds; the fiscal take of the church, and shifting settlement patterns in the northern lowlands. It is the coinage that shines a light on this ‘Dark Age’.

I also looked at finds from the emporium of Eoferwic. The number of finds on the site at Fishergate paled compared to Hamwic (Southampton) and didn’t even make the top-20 most prolific sites in the north! I struggled to see it as the bustling emporium of a wealthy Northumbria.

My thesis, with dataset, is available online from BAR Publishing.

What is your most treasured coin?

As I was preparing to submit my thesis, I had a eureka moment. I recall the time and date precisely: 11:45am on 4th April 2016! Discussions with medievalists at York had led me to attempt to interpret the inscription on variety Cii of the York group. The earliest

interpretation I was aware of was in Withy and Ryall’s English Silver Coins, where a specimen of variety Ci was illustrated on the supplementary plates (drawn by Charles Hall, 1773).

The standard and style of literacy were comparable to the medalet associated with Bishop Liudhard, who was in the entourage of Queen Bertha of Kent. It dawned on me that after Bishop Paulinus fled York in 633, following King Edwin’s death at the hands of Penda of Mercia, the See of York remained vacant until after the transition of the coinage to silver – or at least to pale gold.

Hence, there could only be one candidate as issuer of variety Cii of the York shilling. I carefully examined the inscription on my specimen, then unique, and, following the precedent of the Liudhard legend, was able to read Paulinus Ep, despite the literacy falling short of perfection – as indeed it does for the Liudhard piece.

Therefore, undoubtedly, my favourite coin is the ‘Paulinus shilling’, especially when paired with my gold shilling of Eadbald of Kent, which I speculate (in BNJ 89) was initiated by Paulinus’s colleague Mellitus.

Mellitus became Bishop of London from 604 to 616. When Eadbald came to the throne of Kent he retained his paganism and exiled Mellitus. Soon after, he did convert and Mellitus returned to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

Both Paulinus and Mellitus would have a sophisticated understanding of the economic and symbolic uses of coins. I particularly favour the York coin, as it was found by a close neighbour. I featured the obverse image on the front covers of both of my Sylloge and my thesis.

And your favourite sceats?

It is difficult to know where to start!

Get thee behind me Satan!

Of course, there are the other rare Northumbrian issuers: Æthelwald Moll, both with Æthelred and his joint issue with Ecgberht, and then Eardwulf.

Among the Southumbrian varieties, there are many rare types which exude charm. Series Q, with its affinity for the Northumbrian ‘fantastic beast’, is a particular favourite. Also, those coins in Series J, which when paired, tell the story of the triumph of Good over Evil – unless I’ve arranged them in the wrong sequence!

The Tony Abramson Collection of Dark Age Coinage is scheduled for auction from the Autumn of 2020. Part I will include over 300 lots of choice early Anglo-Saxon gold shillings and silver pennies – the strength of the collection is in its broad coverage of this coinage. Many varieties are extremely elusive, and Part II will include many lots of the highest rarity. Future auctions will focus on the coinage of Northumbria, offering collectors of this fascinating and literate series the opportunity to acquire many exceptional types, and Continental gold and silver of this early coinage found in England.

In all the collection includes over 1,200 coins, previously housed at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, of many of which are unlikely to be made available to collectors again for a generation.