One of the root causes of the First Opium War was a trade imbalance between China and Britain. Over two or more centuries, demand had grown in European countries for luxury goods from China, notably tea, porcelain and silk. The Chinese required payment in silver and trade was so great that eventually there was fear across Europe of a silver shortage. It is thought that opium had been introduced into China in the 5th or 6th century for medicinal purposes. Initially its use was limited but the practice of smoking opium, introduced in the 17th century, caused widespread addiction. The British East India Company began growing opium in India and found it a useful, and high value, commodity which helped redress the trade deficit with China. By 1729 in a renewed attempt to rid China of the addictive drug, the sale and smoking of opium was banned by the Chinese government.

However, the ban was ineffective and opium use increased as the habit of smoking it spread north and west from Canton to affect every class of Chinese society. The situation became serious enough for the Qing government to issue a further ban in 1796. In defiance, imported opium was unloaded onto floating warehouses anchored off islands in the Pearl River delta and then sold to Chinese smugglers, whilst the legitimate cargo continued on to Canton.

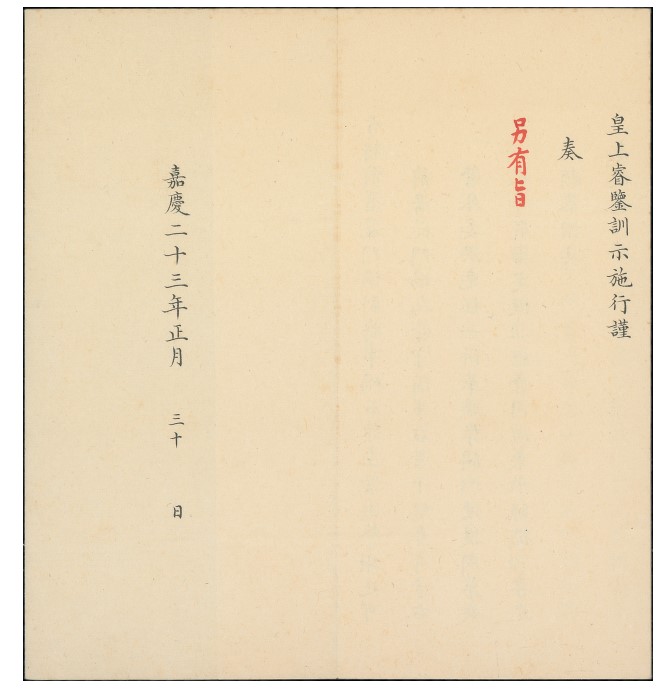

Meanwhile, Americans began trading in opium from Turkey. Of a lower quality than Indian opium, the competition drove down prices, resulting in a dramatic increase in both use and demand By 1838 there were millions of Chinese opium users and the government took decisive action. The Emperor sent Special Commissioner Lin Zexu to Canton. He quickly arrested Chinese opium dealers and demanded that foreign firms hand over all opium stocks, without compensation. Initially they refused but when placed under virtual siege were forced to give up their opium. The quantity recorded as over 1,000 tons, and is said to have taken 23 days to destroy.

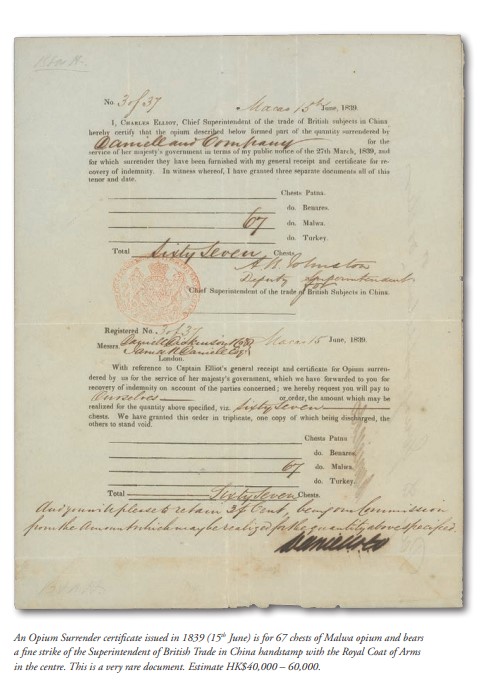

British traders demanded compensation from their government for their losses; however, the British authorities considered the Chinese to be responsible for such payment. Captain Charles Elliot, the plenipotentiary (a diplomat with full government powers), began a series of negotiations to explore a solution that would be acceptable to both parties. Despite his efforts, matters soon deteriorated and British merchants and their families were expelled, first from Canton and later from Macao where they had sought refuge. They were eventually encamped on the merchant fleet sheltering in Hong Kong harbour.

In an attempt to force the re-opening of talks, two naval warships, the Hyacinth and the Volage were ordered to block the port of Canton to all commercial traffic; the resulting loss of revenue would force the Chinese to negotiate. An agreement was reached but when one clipper ship, the Thomas Coutts, broke the blockade as there was no opium on board, the Chinese perceived the weakness in the situation with the British block and tore up the agreement. A second ship, the Royal Saxon, also tried to break the blockade; the warships fired warning shots across its bow. Chinese war junks were sent out to protect it so it could dock and unload its cargo and advanced on the Volage. They refused the order to stay away and the Volage opened fire on them. In less than an hour, four war junks had been sunk and war had begun.

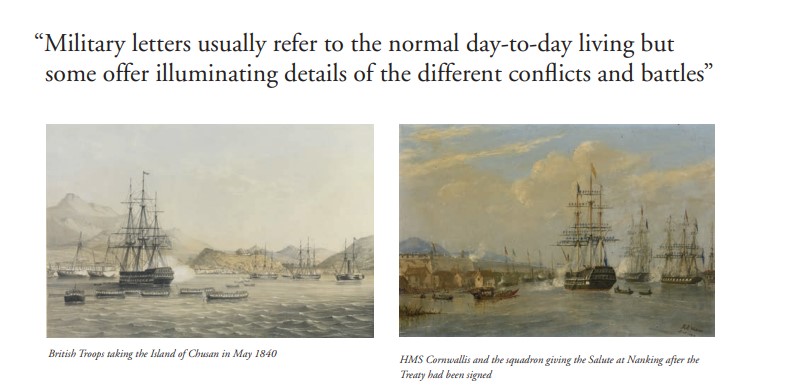

The British prepared an Expeditionary Force (the Eastern Expedition) from India and Britain. It took several months to get the ships, soldiers and supplies ready and organised in Hong Kong, as illustrated in a business letter written on 1st July 1842 from Turner & Co in Macao to Gladstone & Company in Liverpool – the sender noted that Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane made the journey from England to Hong Kong in just 90 days on the HMS Vindictive. The blockade of Canton was re-imposed and the first task facing the Eastern Expedition was to take the island of Chusan, just south of Shanghai, on 5th and 6th July 1840. A military garrison was established on Chusan.

This act of force was successful in bringing the Chinese back to the negotiating table for talks relocated to Canton. Dissatisfied with the previous negotiations, the Chinese appointed the High Imperial Commissioner, Kishan, to negotiate with Captain Elliot. Negotiations were challenging and a further show of naval and military strength was effected. In January 1841 the two Bogue forts guarding the entrance of the Pearl River were taken. Against the wishes of the military, who wanted to advance on Canton, Elliot persisted with negotiations until, finally, a new Treaty was agreed. The island of Hong Kong was ceded to the British (selected in favour of Chusan) alongside a settlement of $6 million and re-opening of British trade in Canton.

Unfortunately, neither government was happy with this agreement. Lord Palmerston felt that Elliot had not extracted sufficient concessions and thus he was replaced by Sir Henry Pottinger, who was keen to employ the available military might. Pottinger sought compensation for the opium confiscated and the costs of the war; the opening of further ports to international trade; and the establishment of diplomatic relations. Again Canton was blockaded. Another northward-bound expedition was organised and Chusan was retaken. This re-established British control over Tinghai’s important harbour. Ningpo, home to one of the imperial cannon factories, was also swiftly overpowered.

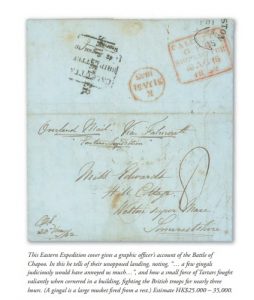

Fighting ceased during the winter of 1841 allowing the British to replenish supplies. The threat of the British had previously been continually downplayed but when the Emperor discovered the severity of the situation he dismissed the officials involved and began to fortify Chinese towns and cities. In spring 1842 the Emperor ordered the retaking of Ningpo. The Chinese did not succeed; instead they prompted the British to recommence their campaign and on 18th May the Battle of Chapoo saw the capture of this important harbour.

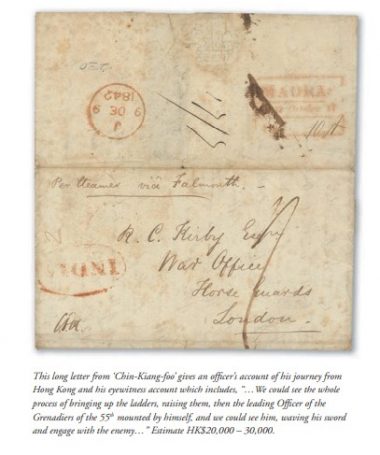

The British were now in a position to move up the Yangtse River and on 16th June successfully overpowered Woosung (16th June); Shanghai was taken before a hard-fought fight to secure Chinkiang. The British then set sail for Nanking. Before battle commenced officials in the city agreed to a request to negotiate. The negotiations lasted several weeks before final agreement resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Nanking on 21st August 1842. The Chinese delegation signed on board HMS Cornwallis. The Treaty of Nanking abolished the Cohong system and their thirteen factories in Canton were effectively closed down. In addition to Canton, Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo and Shanghai became Treaty Ports where foreign merchants were allowed to trade with the Chinese. The Chinese government was to pay $21 million in instalments over three years as compensation for the loss to the traders in Canton and for war reparations.

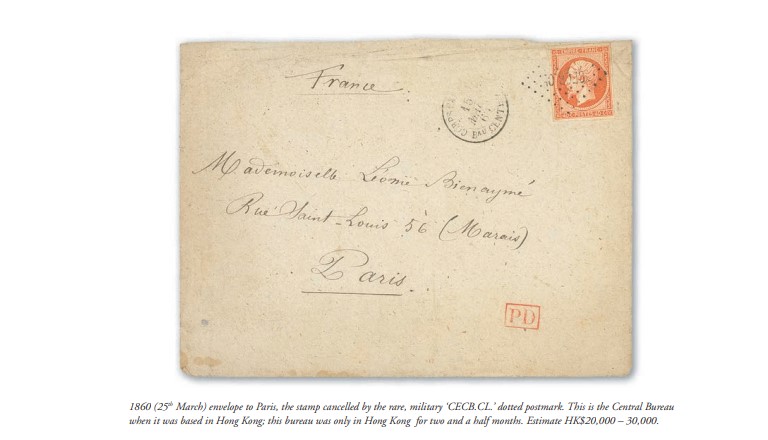

Two main types of letter that make important contribution to understanding this war are those from merchants and some from the military. The merchants’ letters included the latest news; however, it took some five months for a letter to reach England, therefore frequent letters were written to keep the trade business informed. Military letters usually refer to the normal dayto-day living but some offer illuminating details of the different conflicts and battles. They were usually sent from a navy ship at anchor near one of the ports or occasionally from one of the garrisons camped on land.

The Second Opium War

Neither the British nor the Chinese were happy with the Treaty of Nanking. China felt that this was an unequal treaty while Britain wanted more trade and to be able to sell opium legally. There were repeated acts of aggression against British subjects with occasional retributive action by British forces. At this time China was also embroiled, among other disputes, in the Taiping Rebellion, which had started in 1850. This was a bitter conflict that took an estimated 20 million lives before it finally came to an end in 1864. The Emperor was trying to solve the issue of opium which continued to be sold illegally by the British at the same time as quelling the ‘Christian’ rebellion.

The final act which ignited open conflict was when the British-registered cargo ship the Arrow was boarded by Chinese officials on suspicion of piracy, arresting 12 of the 14 Chinese crew members as well as taking down the British flag. Hostilities escalated and in October Britain destroyed the four barrier forts and sent a warship up the Pearl River which began firing on Canton. Trading ceased and a stalemate ensued. In December the foreign factories were burnt down.

It was around this time that France joined the British military expedition using the excuse of the murder of a French missionary in the interior of China early in 1856. There were delays in assembling the forces in China as British troops were diverted to India to help quell the Indian Mutiny. The allies began military operations in late 1857. They quickly captured Canton and deposed the city’s governor, Yeh Mingchen. In May 1858 allied troops in British warships reached Tientsin and forced the Chinese into negotiations. The Treaty of Tientsin, signed in June 1858, provided residence in Peking for foreign envoys, the opening of several new ports to Western trade and residence, the right of foreign travel in the interior of China, and freedom of movement for Christian missionaries.

The British withdrew from Tientsin in the summer of 1858, but they returned to the area in June 1859 en route to Beijing with French and British diplomats to ratify the treaties. The Emperor had ordered the Mongol general Sengge Rinchen to guard the Taku forts; he reinforced them with new artillery pieces and 4,000 Mongol cavalry. The Anglo-French forces insisted on landing at Taku and escorting the diplomats to Peking. The Chinese refused to let them pass by the Taku forts and proposed an alternate route to Beijing. The British-led forces decided against taking the other route and instead tried to push forward past Taku. They were driven back with heavy casualties. The Chinese subsequently refused to ratify the treaties, and the allies resumed hostilities.

Once the Indian Mutiny had been quelled, Sir Colin Campbell, commander-in-chief in India, was free to amass troops and supplies for another offensive in China. In August 1860 a considerably larger force of warships and British and French troops destroyed the Taku batteries and proceeded upriver to take Tientsin. The Emperor dispatched ministers for peace talks but the British diplomatic envoy, Harry Parkes, apparently insulted the Imperial emissary and word arrived that the British had kidnapped the prefect of Tientsin.

Parkes was arrested on 18th September along with the other diplomats and many were tortured to death. At the same time the Anglo-French forces clashed with Sengge Rinchen’s army at the battles of Tunchow and Baliqiao (Eight Mile Bridge), defeating them resoundedly after their doomed frontal charges into the new Armstrong field guns, their rate of fire and accuracy being deadly. In October Peking was taken and, in retaliation for the treatment of the diplomats, the Summer Palace was plundered and then burned. Later that month the Chinese signed the Peking Convention in which they agreed to observe the treaties of Tientsin and also ceded to the British the southern portion of the Kowloon Peninsular.

The outstanding Opium War Collection will be offered for sale in Hong Kong on 14th January 2022, with full details of all lots in our lavish and informative catalogue or on our website. For further information, please contact Neill Granger, [email protected].