Annabel Schooling

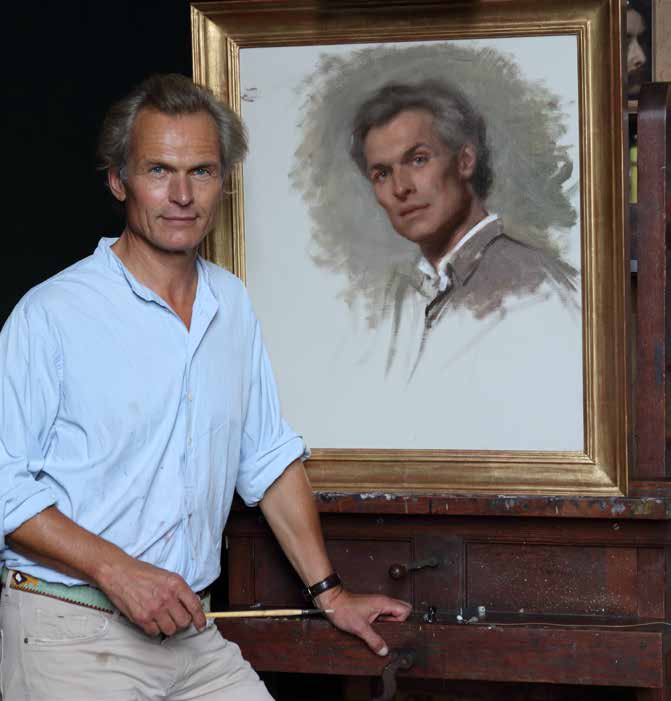

TRICK OF THE LIGHT: AN INTERVIEW WITH SWEDISH PORTRAIT PAINTER URBAN LARSSON

Studying for a BA in History of Art at Stockholm University, Urban Larsson was drawn to the craftsmanship of the Old Masters. He speaks of Titian’s portrait of Pietro Aretino, the famed author and satirist. Painted by Titian in 1545 for the Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici in his later manner, it was once described by Aretino as being ‘piu tosto abozzato che fornito’ – more sketched than finished. The Pietro Aretino is in fact, one of the earliest life sized portraits that utilises the sight-size technique so to appear ‘perfect at a distance’ (Vasari, Lives of the Artists). Larsson uses this technique himself, having been taught by two influential American painters, Charles H Cecil and Daniel Graves, in the atelier tradition at Studio Cecil and Graves in Florence (which became Charles H Cecil Studios in 1991, and where Urban has taught for the past 10 years). In this method, the painter stands back several paces away from the object he is trying to paint, so that ‘lack of harmony and proportion … and in the colours of objects … is more readily seen’ (Da Vinci, Tratatto della Pittura). It is less of a technique, but rather a philosophical mantra of subordinating the details of a painting to the whole, in an attempt to capture the essence of the sitter.

You can see this within Larsson’s softly lit portrait of HM Queen Silvia of Sweden (oil on canvas, 2013). The viewer is drawn in by the warmth of her gaze, and the occasional glint of her pearls, but the painting is not infinitely detailed. The only motif present is the books that lie beside her on the table, referring to the number of organisations of which Queen Silvia is a founder and trustee, including Stiftelsen Silviahemmet (training healthcare professionals in dementia care) and Mentor (supporting the wellbeing of children and young adults). This was a feature that the two came up with together, especially with Stiftelsen Silviahemmet being a foundation close to the Queen’s heart since the death of her mother with Alzheimer’s in 1997.

"You try to go deeper than just a flash of a second"

Urban Larsson: Painting from life, De Mesdag Collective

Painted entirely from life over eight sessions, the portrait was commissioned in honour of the Queen’s 70th birthday, and hangs in the Swedish National Portrait Gallery. She posed for two and a half to three hours, with breaks, talks and listening to music. Naturally I proceed to ask Larsson about the music choice.

“A lot of Bach”, he says with a rueful smile, talking of Queen Silvia’s uncle who was organist at St Nicolas’ Church in Leipzig, Germany, where Johann Bach was music director from 1723-50. Larsson also placed a mirror behind his easel, something he does regularly both for himself (allowing him that dimension of space which is critical to the sight size technique) and his sitter (often an intriguing process seeing the portrait develop). He says was never once intimidated by his subject, who was elegant, well spoken (a natural polyglot who speaks six languages) and empathetic. Larsson seems more interested in portraying the person, as opposed to simply the occupation – a difficult task considering his past commissions have included international government officials, ambassadors, prime ministers, and mayors. His often-used metaphor for painting a portrait is that it is ‘like walking on a tightrope’, where the balance has to be kept between intuition and logical analysis.

“This is seldom straightforward, sometimes the vision that you set out to accomplish changes, and you have to walk in a different direction. When starting a portrait you have to quickly find a pose, a light, a position which fits the person and their physiognomy, as well as an inspiring and challenging pose artistically. You get to know the sitter through the sittings and sometimes it can be more difficult to paint somebody that you know through the emotional affinity or preconceptions about how they look.”

In his non-commissioned pieces, Larsson is free to depict whatever he so wishes. Woman (Eve) (2016) is a classic female nude, reminiscent of the marble Knidian Aphrodite (Praxiteles, 350BC) or the Hellenistic Venus de’ Medici (Unknown, 1st century BC). Depicted alone and expelled from Paradise, she stands unabashed in her nakedness, her face serene amid the dying light. Initially drawing a charcoal sketch of the figure, Larsson was drawn to the iconography of Eve typical to the high church (see Flemish painter Peter Paul Ruben’s The Fall of Man, 1629).

“The depiction of Adam and Eve in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries onward was of course indelibly linked with what the church preached. It was Eve who tempted Adam. Still today in many strict Muslim countries women are second-class citizens and have to cover their hair and body. The idea behind this painting was to strip away those overtones, and instead celebrate Eve as the woman who has given the gift of knowledge to mankind.”

The composition came to Larsson before the concept, having wanted to capture the grace and fluidity of his life models (often Greek or Italian dancers). Similarly, Larsson painted Lachesis (2019), where he paints a beautified version of one of the three Greek Fates (or the Moirai, powerful mythological figures closely associated with death). Here, Lachesis unusually sits alone without her sisters, holding the woven thread of life aloft. Her hands form the main focus, like a musician playing with her strings, as does the swan-like extension of her body. Larsson says he actively tries not to glamorise his subjects, although beauty and harmony are indeed very important aspects of his work.

“By working sight size you try to depict the essence without emphasising the particulars. This has a visually beautifying effect. It is also a question of composition which works in a visually satisfying way. When painting non-commissioned work, the charisma of the model is very important, but also the understanding and interest in the process. Most are dancers which mean that they have a physical ‘awareness’ of their body, and they can hold a pose very well.”

Larsson clearly has this drive to paint, a need to create something in which he can ‘blow life into’. In the Stockholm Review, Larsson talks of a poison that was awoken in him after the first few months painting at Studio Cecil and Graves in 1988. Breaking with family tradition, Larsson decided to leave his Architectural studies after one year at the Royal Institute of Technology; an idea which had gradually grown very strong after the emotional pull he experienced in Florence. Both his parents were incredibly supportive when Larsson told them he had to follow his heart, but his mother pointed to the difficulty of making a living.

“My aunt, a sculptress and teacher, and her husband, a painter, had shown her how difficult it was for them to make ends meet as an artist. Maybe naively, but I had not thought about wanting to make a living from being an artist; I just wanted to paint. It has always been my survival instinct not to look too far forward into the future, because of the potential financial insecurity. This was my way of protecting myself from economical pressure. The only way, as an honest artist, is to stick to your ideals and concentrate on producing work that means something to you. If you think too much about the commercial side, I think you lose the emotional input and in that way you’re biting yourself in the tail”.

Despite Larsson not chasing after commercial success, international success has come to him nevertheless – with exhibitions in New York, Amsterdam, Paris, Florence, and London. He has had ten years exhibiting with Skaj Antiques in Stockholm, in the kind of symbiotic relationship that most artists can only dream of. Indeed, it was the critical success of his first solo show at Skaj in 2011 that prompted Larsson’s commission of Queen Silvia. His most recent show at Skaj (10th-20th November 2022) consisted of over fifty paintings, most completed in the past two years. All of which Larsson drove from his studio in Amsterdam, where he has resided since 1991.

For further information on exhibitions, publications, commissions, further press coverage and to view Urban Larsson’s portfolio, please visit www.urbanlarsson.com